Crane

鹤 (仙鹤)

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

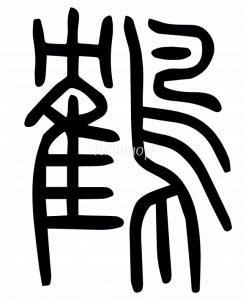

According to the oldest dictionary in China, Shuowen jiezi 说文解字 (Explanations of Simple Graphs and Analyses of Composite Graphs), the earliest version of the character for ‘crane’ is a composite graph consisting of a pictograph for a bird, the present-day character niao 鸟, at the right, with feet and a feathered tail, along with a sound element at the left indicating how the character should be pronounced at that time.

With the exception of the magical bird fenghuang (凤凰, phoenix), roughly translated into English as ‘phoenix’, the red-crowned white crane is the most auspicious of all birds in China and a widely revered creature in popular religion, mythology and among literati.

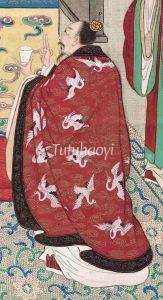

In the chapter entitled ‘Discourse on Forests’ 说林训 of The Huainanzi 淮南子 (The Discourses of the Huainan Masters), a book containing some debates held in the court of Prince of Huainan (179–122 BCE) before 139 BCE, the crane’s life is said to be ‘up to 1,000 years, during which it can fly freely to its heart’s content.’ As one of the most common symbols of longevity in China, the bird is often depicted in the company of other symbols of great age, such as the shou 寿 character, the peach 桃, the pine tree 松, the tortoise 龟, the lingzhi fungus 灵芝, garden rock 寿石, the emblem of the Eight Daoist Immortals 暗八仙, or the Longevity God of the South Pole 南极仙翁, to enhance their potency. The high-soaring crane often serves as the mount of immortals and fairies and is also supposed to lift those mortals who have just attained immortality up to heaven. Naturally, formal Daoists’ gowns bear flying cranes as a decorative motif and the combination of cranes and the Eight Trigrams known in Chinese as bagua 八卦 often adorn Daoist ceremonial utensils.

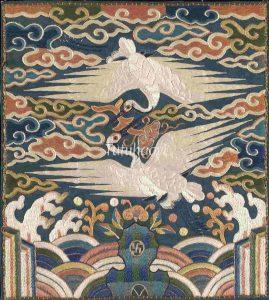

The crane’s qualities of sacredness and gentlemanliness acquired their ultimate recognition when, during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1911), the most senior grade of imperial civil servants – the highest-flying, oldest, wisest, and most dutiful ‘sons’ of their imperial ‘father’, the emperor – wore a white crane rank badge or mandarin square in front of their chest.

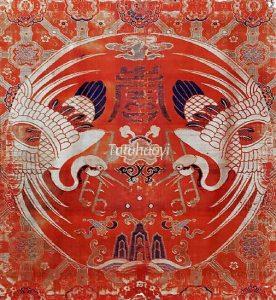

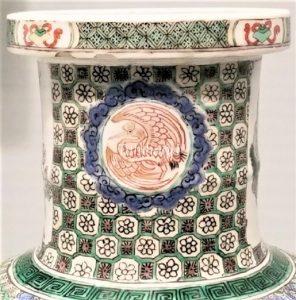

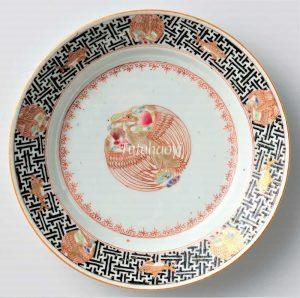

Artists often confine the crane within a circle since the roundness indicates ‘perfection’, resulting in a frequently encountered ‘crane medallion’ design, known in Chinese as ‘tuanhe wen 团鹤纹’.

Lack of knowledge in a specific culture would lead to a slip of putting the boot on the wrong leg, as is the case of identifying the longevity icon crane, in the context of symbols of the similar kind such as peaches and the lingzhi fungi, as a ‘stylized pelican’, which very rarely features in Chinese pictorial tradition.

literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

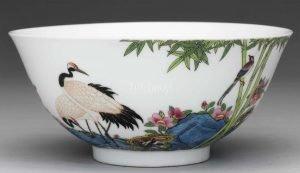

Related Figural Story:

One qin zither and one crane 一琴一鹤

Related Blog:

How do Chinese combine symbols in pictorial art to increase the potency of the longevity concept?

Fig 1: blue-and-white bowl, 16th century, courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

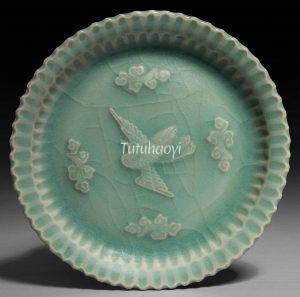

Fig 2: dish with flying crane and clouds in relief, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

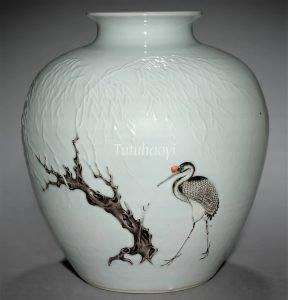

Fig 3: jar with crane and willow in relief, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Fig 4: Chinese symbol 鶴 in calligraphy format

Fig 5: fabric, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 6: porcelain bowl, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Fig 7: round box with lid, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Museum of East Asian Art (Cologne)

Fig 8: blue-and-white vase, 1521–1620, courtesy of Princessehof Museum, Netherlands

Fig 9: porcelain dish, Tianqi period (1621–27), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 10: falangcai bowl, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

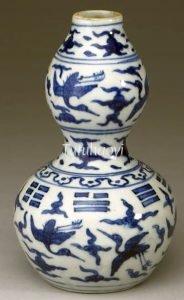

Fig 11: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, Jiajing period (1521–67), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

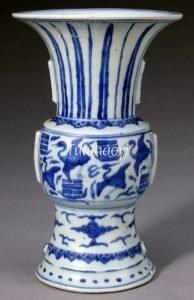

Fig 12: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, Jiajing period (1521–67), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 13: hanging scroll (detail), ink and colour on silk, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), location to be confirmed

Fig 14: mandarin square for the first-class civil servants, embroidery, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum

Fig 15: porcelain vase with overglaze enamelled decoration (detail), Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Fig 16: embroidery medallion, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Krakow National Museum, Poland

Fig 17-18: porcelain dish with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, first half of the 18th century, courtesy of the Sotheby’s auction house

Fig 19-20: porcelain plate with overglaze enamelled decoration, ca. 1725–49, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam