Dragon

龙

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

The fifth creature of the Chinese zodiac, the long dragon is one of the most complex and multilayered of all Chinese symbols. Its ferocious energy binds together all the phenomena of nature: bringing benevolent rain, but also typhoons; shaping the landscape, and causing earthquakes. One of the guardian creatures of the cardinal directions, the long dragon stands in the east, the source of the sun, spring rain and fertility.

Long dragons appear in several different forms in Chinese mythology – those with scales are called jiao long 蛟龙, those with wings ying long 应龙, those with horns are qiu long 虬龙, and small-sized ones are chi long 螭龙. Despite their ferocity, these mighty beasts are also fundamentally beneficent, the most auspicious of all creatures and embodiments of masculine vigour and the concept of yang 阳. Because of these associations, the dragon, particularly one with five claws, was the symbol par excellence of the Chinese emperor, the Son of Heaven, and is often found embroidered on imperial robes. It is also the embodiment of the land – quite literally at times, for the features of the landscape were seen by some to be the features of an enormous dragon. This dragon would sleep under the earth during the winter, then ascend to the skies on the second day of the second month, bringing the first spring thunder and rain. For masters of feng shui, underground currents are the veins of this great dragon, and therefore ought not to be disturbed by human builders.

literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

Related motifs:

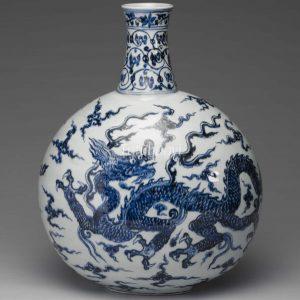

Fig 1: blue-and-white moon flask, Yongle period (1403–24), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

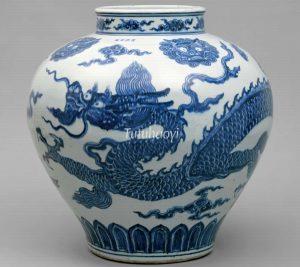

Fig 2: meiping vase, 14th -15th century, courtesy of The Guimet Museum, Paris

Fig 3: porcelain jar, Xuande period (1426–35), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

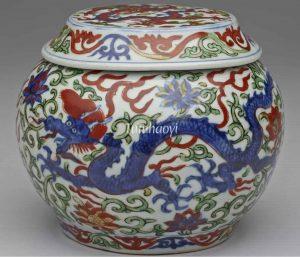

Fig 4: lidded porcelain bowl, Xuande period (1426–35), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

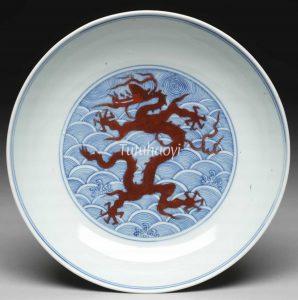

Fig 5: porcelain dish, Zhengde period (1506–21), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 6: censer, Jiajing period (1522–1566), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Fig 7: incense burner, 1564, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig 8: wucai tea jar, Wanli period (1573–1619), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 9: porcelain dish, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 10: porcelain dish, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

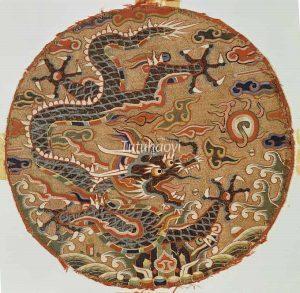

Fig 11: medallion, late 17th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

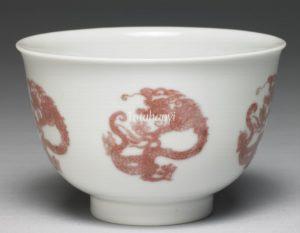

Fig 12: porcelain cup, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 13: porcelain tea jar, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 14: porcelain dish, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

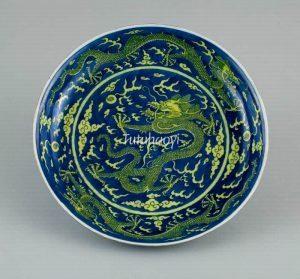

Fig 15: porcelain dish, Jiaqing period (1796–1820), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago