Horse

马

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

No animal has exercised as much influence over the destiny of China as the horse, which was central to the power of the various mounted nomadic peoples who dominated north China during the Period of Disunion (220–581CE), and the entire empire under the Mongols (Yuan dynasty, 1271–1368) and Manchus (Qing dynasty, 1644–1911). The long queue (tail) of hair, which all Chinese males were obliged to wear under the Qing emperors, is said to have been inspired by the horse’s tail – an ever-present reminder to the emperors and their Chinese subjects of the animal on which their armies had swept down into China, ousting the native Ming. Indeed, it was the Chinese who – possibly borrowing the idea from nomads – first invented stirrups, making riders more stable and agile, and cavalry a more efficient weapon of war. Before then, in ancient China, horses had been prized primarily as fast draught animals, pulling swift coaches for the wealthy, and chariots on the battlefield. Other wheeled transportation was drawn by oxen.

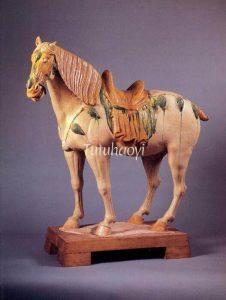

Ceramic models of horses produced during the Wei dynasty (386–557CE) were much admired and imitated by later Chinese artists, and the sport of polo, which was imported from Iran, became popular among the cosmopolitan aristocracy of the ensuing Tang dynasty (618–907CE).

A horse’s much-admired swiftness and power are reflected in its classification under the element fire, and it is also therefore associated with the direction south. The difficulty of taming and riding a frisky horse may account for the term ‘horse-will’ used in the famous novel Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en (吴承恩 ca.1500 – ca. 1582) to describe a headstrong and impulsive nature.

Reference:

Yibin Ni (2009), 一百个漢字 Symbols, art, and language from the land of the dragon: The cultural history of 100 Chinese characters, Duncan Baird Publishers Ltd, London

Related Pun Rebus:

Fig 1: earthenware with three-colour (sancai) glaze and pigment, late 7th–first half of the 8th century, Tang dynasty (618–907), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig 2: cobalt blue splashed earthenware with a clear glaze, Tang dynasty (618–907), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 3: porcelain saucer dish, c. 1600–1624, courtesy of The Royal Society of Friends of Asian Art, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Fig 4: covered ewer, ca. 1644–83, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig 5: porcelain bowl with overglaze enamelled decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

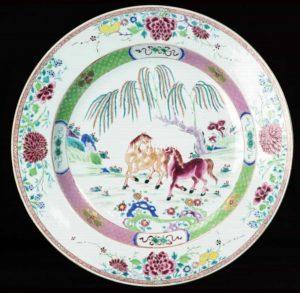

Fig 6: porcelain charger Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Cohen & Cohen, Chinese Export Porcelain and Oriental Art (The elephant in the room; October 2019)