Phoenix

凤凰

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

The feng phoenix, or feng huang 凤凰, which is often portrayed to resemble a peacock or golden pheasant, is the second of China’s Four Sacred Creatures (the others being the long dragon 龙, the qilin 麒麟 and the tortoise). Except in its mythic status, this creature is not related to the fabulous fire-born bird of Mediterranean and Near Eastern mythology. However, the feng phoenix is linked with heat, since it is the guardian of the south, and therefore a symbol of the sun, summer warmth and harvest.

The Chinese phoenix is sometimes interpreted as a male (yang) animal, but when accompanying the (male) dragon it represents a wife, and pictures of a dragon and phoenix together symbolise marital bliss. As the imperial dragon was a symbol for the emperor, the phoenix was the particular emblem of the empress, and a woman on her wedding day might wear a dress adorned with the phoenix to show that she was ‘empress for the day’.

In Chinese literature, the body of the phoenix is sometimes said to represent the Five Good Qualities: virtue (the bird’s head); humanity (the breast); reliability (the stomach); duty (the wings); and proper ritual conduct (the back). Like the dragon, the phoenix has important imperial associations. It was said to appear only during the reign of good, just emperors; and, unsurprisingly, artists and poets commonly flattered their imperial masters by declaring that a phoenix had been spotted on their land. Confucius, on the other hand, in his day bemoaned the absence of the phoenix and other auspicious celestial signs.

literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

Fig 1: porcelain teapot, Yongle period (1403–25), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

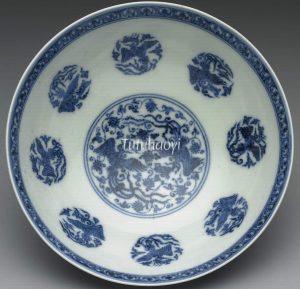

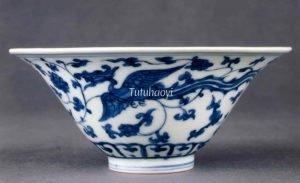

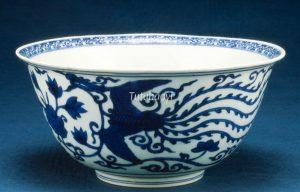

Fig 2-3: porcelain bowl, Yongle period (1403–25), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

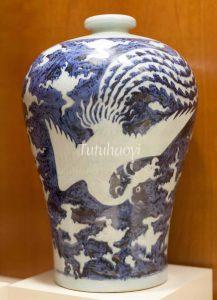

Fig 4: porcelain vase, Ming dynasty, c.1430, courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

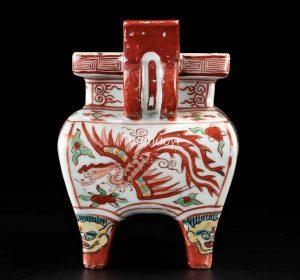

Fig 5: wucai incense burner, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of National Museums Scotland

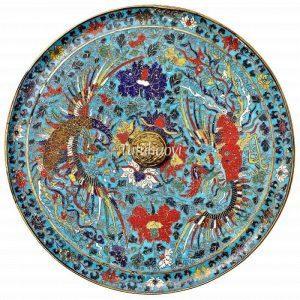

Fig 6: cloisonne mirror, 1550–1644, courtesy of The Penn Museum

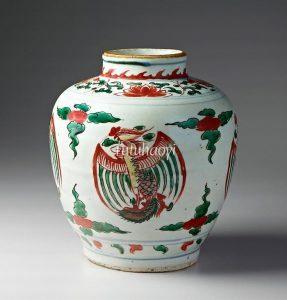

Fig 7: porcelain jar, 17th century, courtesy of Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University

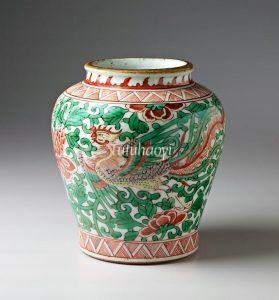

Fig 8: porcelain jar, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University

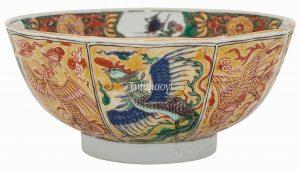

Fig 9-10: famille jaune octagonal bowl, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Jie Rui Tang Collection

Fig 11 & 12: saucer dishes, c.1700–24, courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Holland

Fig 13: porcelain bowl, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

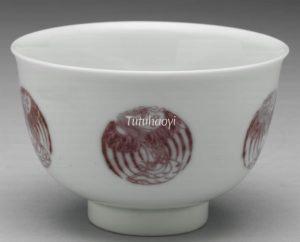

Fig 14: porcelain cup, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 15: porcelain vase, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Fig 16: conical bowl, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 17: porcelain dish, Kangxi period (1662–1722), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Fig 18: porcelain dish, 18th century, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Fig 19: blue-and-white porcelain bowl, 18th century, courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

Fig 20: porcelain bowl, Qianlong period (1736–95), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY