Chang’e the Moon Goddess

嫦娥奔月

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

The Mid-Autumn Moon Festival falls on the night of full moon in the eighth lunar month. Chang’e, the Moon Goddess, is usually associated with this family-union occasion, together with the festival food – the moon cake (月饼). A legend recorded in an ancient Chinese book, The Huainanzi (淮南子 The Discourses of the Huainan Masters), compiled around 139 BCE, says that a beautiful girl called Chang’e (嫦娥) has been living on the moon for thousands of years. Chang’e’s husband was the legendary archer, Hou Yi (or Houyi 后羿), and he was given the elixir of immortality by the Queen Mother of the West (西王母 Xiwangmu) for his merits. Out of boredom and curiosity, Chang’e tasted the elixir. As a result, she turned into an immortal. Her body became so light that she ascended to heaven, ending up in the nearest planet, the moon. On the moon, there was a huge osmanthus tree, a toad, and a hare grinding the tree bark with a pestle in a mortar to prepare some magic cure. The adorable hare became Chang’e’s loyal companion. Chang’e also gradually evolved into the role of the osmanthus sprig giver from the Moon Palace.

In one of the earliest story scenes of Chang’e’s extraordinary feat, she has a human body and a dragon’s rear end. The moon is marked by the toad in the middle. Both Chang’e and the moon are floating among vapour clouds and ball-like stars and planets. This stone carving was excavated from a Han-dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE) tomb in the outskirts of Nanyang city, Henan province in 1964.

On a Tang-dynasty (618–907) bronze mirror in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Chang’e, her entourage, and specific environment attributes are fully displayed. Chang’e appears as a beautiful fairy in a silk gown with sashes flying around her body. The hare has his set of a pestle and a mortar beside him. On the right, there is the huge osmanthus tree, under which is the toad, symbolising the moon, the embodiment of the essence of the yin energy (阴精). The tortoise is a longevity symbol in traditional China because they were believed to be able to live for a thousand years by the ancients. It was added to the scene as the knob of the mirror, since scenes involving immortals are often used as longevity symbols and thus birthday presents for elders.

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Chang’e was still used to adorn daily utensils and display ornaments to imbue the environment with auspicious aura. The cute hare adds femininity to the design and therefore was popular in women’s inner chambers.

literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

Related symbolic motif:

Plucking a Sprig of Osmanthus Blossom from the Moon Palace 蟾宫折桂

Fig 1: stone carving, shallow relief, Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), courtesy of Museum of Carved Stone from Han Dynasty Tombs, Nanyang, Henan Province

Fig 2: bronze mirror with moulded shallow relief decoration, Tang dynasty (618–907), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 3: bronze mirror with moulded shallow relief decoration, Tang dynasty (618–907), courtesy of Zhejiang Museum, China

Fig 4: porcelain jar with underglaze blue decoration, Jiajing period (1522–66), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 5: porcelain hexagonal dish with underglaze blue decoration, Longqing period (1567–72), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Guangdong Museum, China

Fig 6: porcelain wine ewer with underglaze blue decoration, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

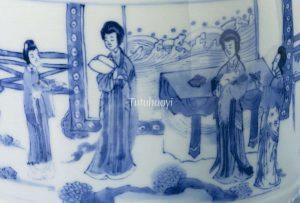

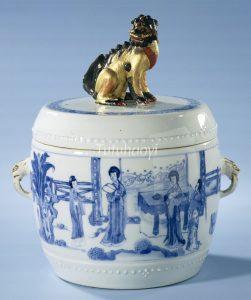

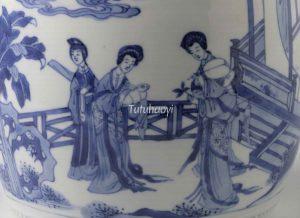

Fig 7-10: two covered tureens with underglaze blue decoration, c.1700, courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Holland

Fig 11-12: covered tureen with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Jie Rui Tang Collection

Fig 13-14: covered tureen with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

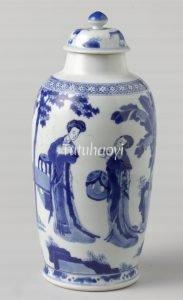

Fig 15: ovoid covered jar with underglaze blue decoration, c.1680 – c.1720, courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Holland

Fig 16: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration (2 sides), Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of The Dresden Porcelain Collection, State Art Collections of Dresden, Germany