Wang Xizhi’s Love of Geese

王羲之爱鹅

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361) is often said to be the greatest calligrapher in Chinese history. He has his biography in the official history of Jin 晋 dynasty (c. 265–420). One anecdote in it concerns his fame for his calligraphic skill and his love of geese. A Daoist priest in the neighbourhood raised a handsome flock of geese. Wang Xizhi paid a special visit to him in order to see the geese and found it hard to tear himself away from them. He pleaded with the priest to sell the flock to him. The geese raiser made him a counteroffer: ‘I will let you have the whole flock if you write a copy of Laozi’s Daodejing (道德经) text for me.’ Wang Xizhi willingly finished the job and went home happily with the geese.

Ever since the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), there are two basic types of composition depicting Wang’s love of geese. One type shows Wang watching geese in the river from the bank; the other features him being offered a goose by his servant or the priest.

literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

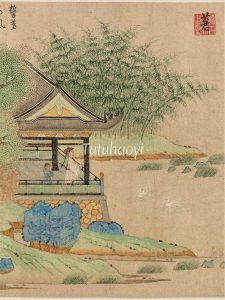

Fig 1: handscroll, ink, colour, and gold on paper (detail), Qian Xuan (1239–1301), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig 2: stoneware pillow with iron red decoration on a white slip, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), courtesy of The Tokyo National Museum

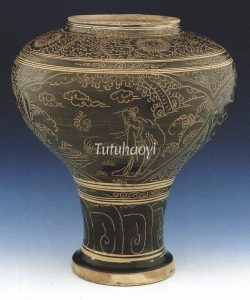

Fig 3: Cizhou-type stoneware jar, Ming dynasty (ca.1368–1450), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

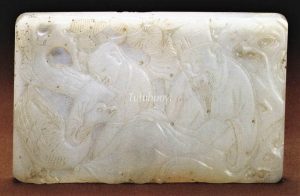

Fig 4: jade shallow relief carving, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of The Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 5: handscroll, ink on paper, Du Jin (杜堇, ca. 1465–1509), courtesy of The Palace Museum, Beijing

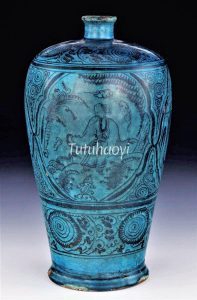

Fig 6: Cizhou-type meiping with underglaze iron-black painted decoration on a cream slip beneath a turquoise glaze, C.1500–1600, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

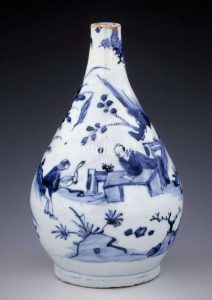

Fig 7: porcelain bottle with underglaze blue decoration, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

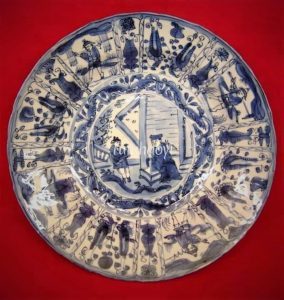

Fig 8: kraak porcelain dish, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Marc Michot Gallery

Fig 9: porcelain bowl, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Capital Museum, Beijing, China

Fig 10: hexagonal porcelain container and cover overglaze enamelled decoration and traces of gilding, Tianqi period (1620–27), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 11: porcelain square dish with overglaze enamelled decoration, Tianqi period (1620–27), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Sir Michael Butler Collection

Fig 12: porcelain bowl with pierced lattice-work panels and underglaze blue decoration, Chongzhen period (1628–44), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

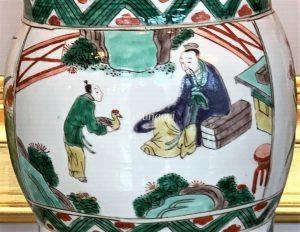

Fig 13-14: porcelain vase with overglaze enamelled decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of The Dresden Porcelain Collection, State Art Collections of Dresden, Germany, photograph by Mr JP Kim

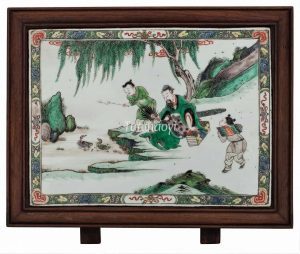

Fig 15: porcelain table screen plaque with overglaze enamelled decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Jie Rui Tang Collection

Fig 16: jade table screen, shallow relief carving, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Harvard Art Museum

Fig 17: carved cinnabar lacquer brush holder, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 18: porcelain table screen with famille rose enamels, 18th century, courtesy of Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University