Bamboo

竹

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

In the current form of the character 竹 zhu, the image of two bamboo stems side by side is still clear. Other ancient forms of the character show the pair gently bending toward one another, illustrating the flexibility of this highly esteemed plant. ‘Young bamboo bends easily’ is one of the many common sayings that refer to bamboo, and no other plant features so often in Chinese folklore, song and art.

Bamboo’s popularity derives primarily from its usefulness, and this fast-growing plant – although in fact it is technically a grass – is still put to a vast range of uses in China. It is useful almost as soon as it starts growing – young shoots are eaten as a delicacy, while thick, mature stems are used as scaffolding, which may seem precarious to the Western eye but in fact is strong and supple. It was once the main raw material for writing – paper being made from bamboo strips, and bamboo stems of varying widths being made, as they still are, into brush handles and pots. So revered was this plant that porcelain brush pots were often made in imitation of their bamboo counterparts.

Bamboo represents youth and suppleness, but also old age, because it is long-lived and evergreen – it is one of the Three Friends of Winter, together with the pine and plum. The word for bamboo, zhu 竹 is a homophone for ‘wish 祝’ and the plant is therefore also depicted in art to reinforce wishes for a range of blessings.

Bamboo’s noble characteristics derive from its ability to bend with the wind while remaining firmly rooted. It therefore represents humility and endurance (sometimes depicted by bamboo with a rock), while the hollow centre symbolises an open heart that is able to learn. These are historically the virtues of the literatus, the gentleman scholar-official, who is often pressured to bow to the wishes of his masters and is subject to the whims of the political climate.

Reference:

Yibin Ni (2009), 一百个漢字 Symbols, art, and language from the land of the dragon: The cultural history of 100 Chinese characters, Duncan Baird Publishers Ltd, London

Related Pun Rebus:

Fig 1: porcelain tea caddy with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 2: porcelain cup, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

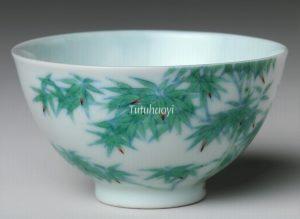

Fig 3: enamel-decorated porcelain bowl, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 4: enamel-decorated porcelain dish, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 5: enamel-decorated porcelain bowl, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 6: porcelain cup, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 7: pair of tea bowls, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

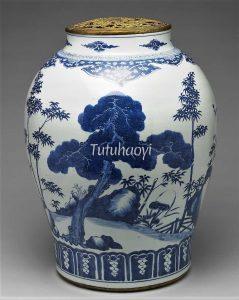

Fig 8: porcelain jar with underglaze blue decoration, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei