Deer

鹿

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

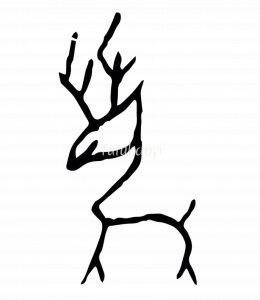

The earliest pictograph of the character 鹿 lu for ‘deer’ is found on a tortoise plastron burnt to crack for divination. Though it is by no means anatomically accurate, the pictograph exhibits the most clearly recognisable characteristics of the animal. It vividly imitates the four legs, slender head, lean body, and prominent antlers. Different scripts of the same word show how the antlers and legs have been evolving to the modern-day character.

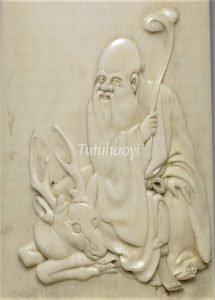

The Piya (埤雅), a Chinese dictionary compiled by the Song-Dynasty scholar Lu Dian (陆佃, 1042–1102) with a preface dated 1125 contains a quotation which says ‘The ancients regarded deer as divine animals’. They were reputed to be able to live for a very long time and, hence, like cranes and tortoises, they are symbols of longevity. Deer usually appears as a companion of the Star God of Longevity (寿星, shouxing), who is an old man with a long white beard and a bulging forehead. For this reason, their velvet antlers are a highly valued ingredient in many preparations of traditional Chinese medicine, and are reported to have the power to prolong life, aid virility and alleviate various ailments.

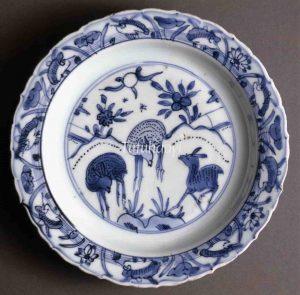

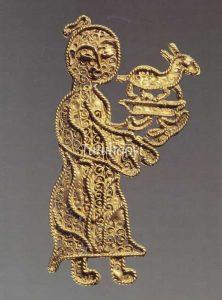

Deer came to represent wealth because the Chinese word 鹿 lu for ‘deer’ is a homophone of 禄 lu for ‘official income’ or ‘emolument’. A blue and white dish painted with a deer bears a four-character inscription which says ‘禄在其中 (Here is your official emoluments)’, explicitly link the deer to emoluments. A gift of an image showing a servant presenting a deer on a tray is a way of wishing the recipient advancement in officialdom and a rise in his pay.

Related Puns and Symbols:

May you have an ample official income 百禄

May you be created a peer and earn a handsome official income 爵禄封侯

Gourd 葫芦

Literature research by Dr Yibin Ni.

Read Dr Ni’s further discussion: How do Chinese artists combine symbols in pictorial art to increase the potency of the longevity concept?

Fig 1: porcelain plate, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 2: porcelain bowl, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum

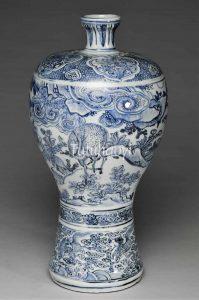

Fig 3: bottle vase with blue and white decoration, Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 4: blue-and-white porcelain dish, c. 1600, courtesy of the Guimet Museum, Paris

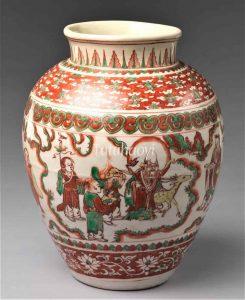

Fig 5: jar with enamelled decoration, Jiajing period (1521–67), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

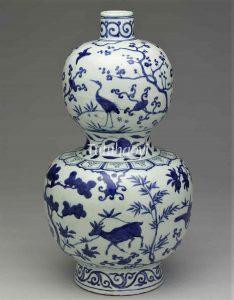

Fig 6: bottle with blue and white decoration, Jiajing period (1521–67), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

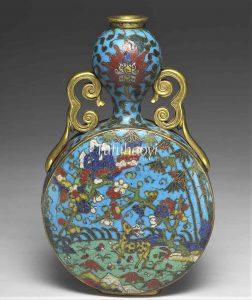

Fig 7: cloisonne enamel bottle, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 8: gold ornament, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the Capital Museum, Beijing

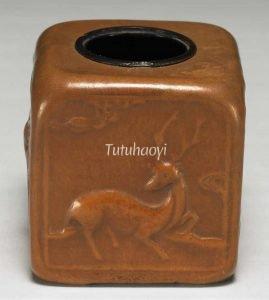

Fig 9: cizhou ware lobed pillow, Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), late 11th /early 12th century, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

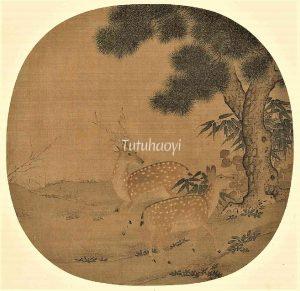

Fig 10: fan painting album leaf, ink and colour on silk, Song dynasty (960–1279), Mou Zhongfu 牟仲甫 (biodata unknown), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 11: Longquan celadon ware dish with shallow relief decoration, 1250–1299, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

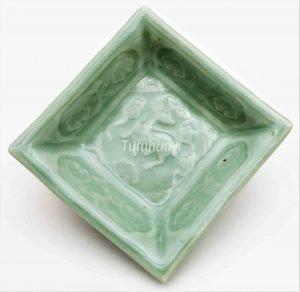

Fig 12: Longquan ware square dish, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Fig 13: blue-and-white lobed dish, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), courtesy of Qingzhou Municipal Museum, Shandong, China

Fig 14: blue-and-white porcelain plate, 17th century, courtesy of Catawiki, Lot 35384239

Fig 15: porcelain dish, 17th century, courtesy of Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University

Fig 16: water dropper made from bottle gourd, Kangxi period (1662–1722) courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 17: porcelain dish, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University

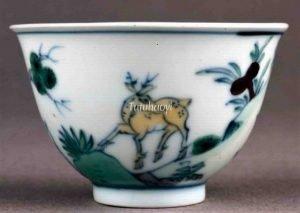

Fig 18: porcelain wine-cup, 18th century, courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 19: ivory armrest, 18th century, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

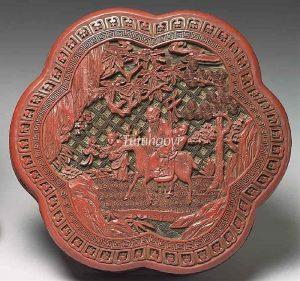

Fig 20: carved lacquer layered box with cover, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 21: a version of the ‘shell-and-bone’ script of the word 鹿 lu for ‘deer’

Fig 22: seal script of the word 鹿 lu for ‘deer’

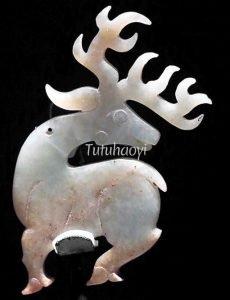

Fig 23: jade carving, unearthed from the Shang-period (ca. 1700–1100 BCE) site of Qianzhangda, Tengzhou, Shandong Province, courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

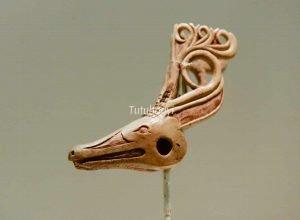

Fig 24: bone carving, Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), unearthed from Tomb No. 28, Jiaohe Valley, Turpan, courtesy of the Museum of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

Fig 25: tomb wall painting of a person ascending to be an immortal on a deer-pulled cart, Eastern Han dynasty (25 CE – 220 CE), unearthed from a tomb in Jingbian county, Shaanxi province