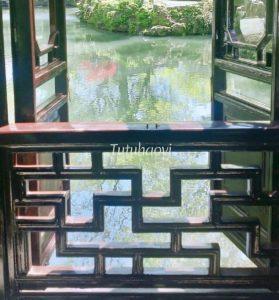

Swastika (the Wan character in Chinese)

卐 (万字)

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

Either the clockwise swastika 卐 or the counterclockwise sauwastika 卍 is used interchangeably in Chinese decorative arts as well as in some religious contexts. Sometimes, the two opposite versions can co-occur on the same occasion without making a difference in meaning. Swastika is a very old symbol in the cultures scattered over the Eurasian continent. In China, it can be traced back to the painted pottery created in the Neolithic Majiayao 马家窑 culture existing from 3300 to 2000 BCE in the upper Yellow River region encompassing present-day eastern Gansu 甘肃, eastern Qinghai 青海, and northern Sichuan 四川 provinces. In the Eastern Han (25CE – 220CE) period, the swastika was introduced to China with Buddhist iconography and became prominent. However, it was not until the Tang Empress Wu Zetian 武则天 (684–704) made her decree that its pronunciation be ‘wan 万’ that it was accepted as a fully-fledged Chinese character, sounding the same as the number 10,000 in Chinese. Roughly speaking, it means ‘the myriad auspicious things in the universe’.

In decorative arts, swastika is often used together with various versions of the character shou 寿, the auspicious Chinese symbol bat, and the longevity symbol peach fruit. In late imperial China, swastika is widely found as the ground pattern on fabrics and on architectural or furniture elements such as paved passage ways and lattice pattern on railings, window frames, and cabinet doors.

Related Pun Picture:

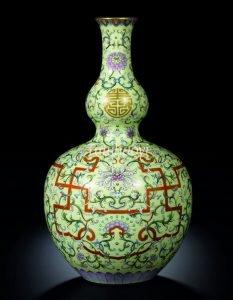

Fig 1: double gourd vase with overglaze enamelled decoration, Qianlong period (1736–95), courtesy of Sotheby’s Auction House, Hong Kong, 2010

Fig 2: porcelain bowl with falangcai decoration, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Bequest of Dr G.E. Morrison, 1921. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

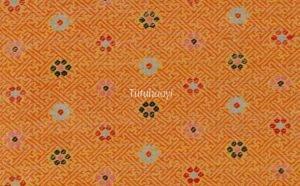

Fig 3: fabric, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 4: architectural drawing, heads of rafters at the Gate of Heavenly Purity, Palace Museum, Beijing

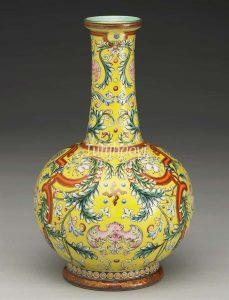

Fig 5: porcelain vase with overglaze enamelled decoration, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 6: porcelain plate with underglaze blue decoration, Daoguang period (1821–50), Qing dynasty, courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Bequest of Howard Spensley, 1939. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

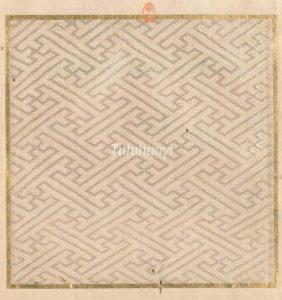

Fig 7: model pattern of swastika, 19th century

Fig 8: wooden lattice (detail), the Humble Administrator’s Garden in Suzhou, China