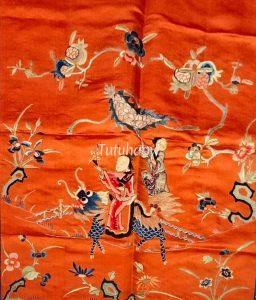

Qilin delivering a child

麒麟送子

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

This is a legendary story about the birth of Confucius (551 BCE – 479 BCE), the renowned philosopher from ancient China during the Spring and Autumn Period (770 BCE – 475 BCE).

According to The Family History of Confucius (孔子家语), Confucius’ father, Shuliang He (叔梁纥), had nine daughters but no sons from his first marriage. His second marriage produced a son, but the child was born with a foot deformity. During that era, based on the prevailing rites and laws, a man without a healthy male heir risked losing his noble status and being reduced to a commoner. In his later years, Shuliang He entered into a third marriage, and from this union, Kong Qiu (孔丘), later known as Confucius, was born.

Folk legends also surround Confucius’ birth. One popular tale tells of how his mother had an extraordinary dream during her pregnancy. In the dream, a qilin, a mythical creature, appeared at her home, accompanied by heavenly music. The qilin spat out a jade book inscribed with the words: “This child is the seed of a noble but born into an unfortunate time. He can only be a ‘king without a throne.’” The next day, Confucius was born, and thus giving rise to the legend of ‘Qilin delivering a child’. In Chinese folklore, the qilin has come to symbolise benevolence and good fortune, and families of virtuous standing often pray to the qilin for the blessing of offspring.

Literature research by Rachel Ma

Related Motifs & Symbols:

Research article from Dr Nibin Yi

Has Jiang Ziya’s mount got anything to do with the Père David’s deer?

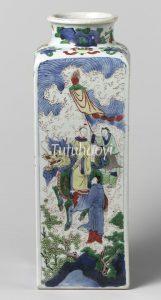

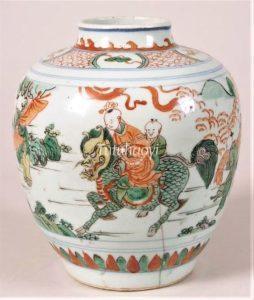

Fig 1: square vase with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, Shunzhi period (1644–61), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

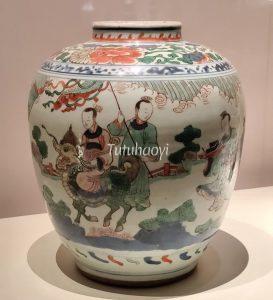

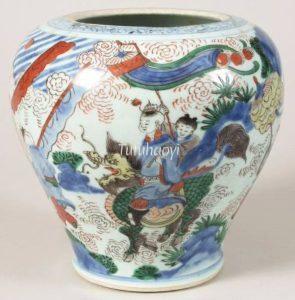

Fig 2: wucai porcelain jar, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Wuhan Museum, Hubei Province, China; photograph by Rachel Ma

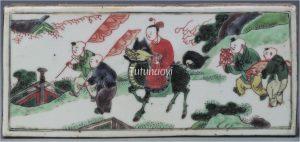

Fig 3: wucai porcelain plaque, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

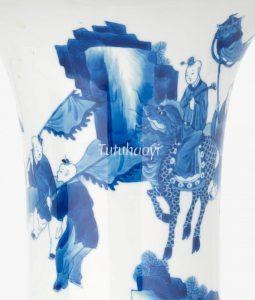

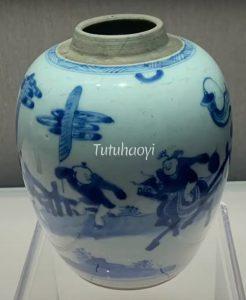

Fig 4-5: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1947. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Fig 6: wucai porcelain jar, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 7: lid of a porcelain box with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Glasgow Museums Collection

Fig 8: wucai porcelain jar, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Princessehof Ceramics Museum, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands

Fig 9: wucai porcelain pot with cut neck, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Princessehof Ceramics Museum, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands

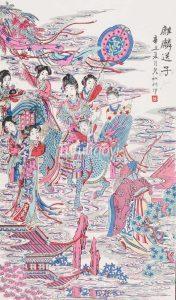

Fig 10: colour woodcut print, 1901, courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig 11: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, the Republican Period (1912–49), courtesy of China Ceramic Museum, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, China

Fig 12: paper fan, the Republican Period (1912–49), courtesy of Nanjing Museum, Jiangsu Province, China; photograph by Rachel Ma

Fig 13: wucai porcelain vase with butterfly-shaped handles, 1936, courtesy of China Ceramic Museum, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, China

Fig 14: embroidered fabric patch, the Republican Period (1912–49), courtesy of Zhejiang Provincial Museum, China; photograph by Rachel Ma