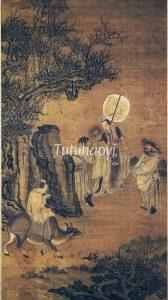

Li Mi Hanging His Books on His Ox Horns

李密牛角挂书

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

‘Li Mi (李密 582–619) Hanging His Books on His Ox Horns’ is one of the inspirational self-improvement stories in ancient China. It was adopted in the famous Three-Character Classic (三字经 San Zi Jing), written in the 13th century. The primer served as children’s first textbook in elementary education for more than five hundred years until the late nineteenth century.

Li Mi was a war lord, politician, and poet during the end of the Sui dynasty (581–618). He was born with a silver spoon in his mouth because both his grandfather and father were from aristocratic families during the Northern Zhou (557–81) and Sui dynasties. He had a noble primary education and developed a good habit of reading. As a young scholar, he heard that the eminent scholar Bao Kai (包恺) was visiting Mt. Gou Shan (缑山), in Luoyang (洛阳), Henan province, and set out to follow him. He put a grass saddle on the back of an ox and used it as his vehicle for the journey. Not wanting to waste time on the way, he carried the Book of Han (汉书) with him. It is a history of the Western or Former Han dynasty from the first emperor in 206 BCE to the fall of Wang Mang in 23 CE. The multi-volume work was compiled by Ban Gu (班固 32–92 CE) with the help of his sister Ban Zhao (班昭 49–120 CE), on the basis of the work of their father, Ban Biao (班彪 3–54 CE). Li Mi held one volume in his hand and hung some of the volumes on the ox horn.

It happened that Yang Su (杨素 544–606), the Duke of Yue (越国公), was riding behind Li Mi on the same road. When Yang Su saw a young man reading on the ox back, he pulled the reins and slowed down the horse. When he approached Li Mi, he asked, ‘Why are you so hardworking, lad?’ Recognising this prominent figure in the country, Li Mi immediately got off the ox back to perform ritual kowtow towards him. Yang Su asked him about the book he was reading and was very impressed by Li’s knowledge and demeanour.

Later, Yang Su told his son Xuan’gan (玄感) that Li Mi was an extraordinary man and somebody he could rely on. Xuan’gan took his father’s words to heart. In 613 CE, Xuan’gan declared an uprising in Liyang (黎阳), near modern Hebi (鹤壁), Henan province, against the Sui emperor. He sent someone to Chang’an (长安) to invite Li Mi to be his counsellor.

image identification and literature research by Dr Yibin Ni

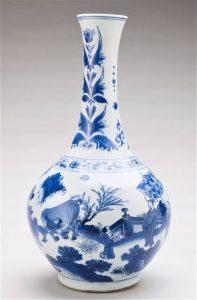

Story Scene Differentiation:

Fig 1: album leaf (detail), ink on silk, attributed to Qian Xuan (1235–1305), courtesy of the Freer Gallery, Washington D. C.

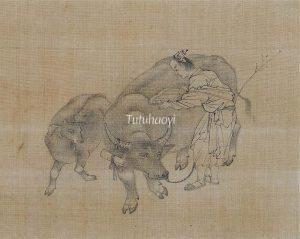

Fig 2: hanging scroll (detail), ink and colour on silk, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the Freer Gallery, Washington D. C.

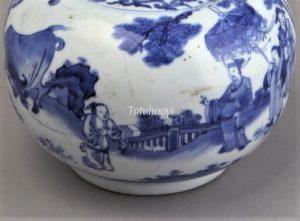

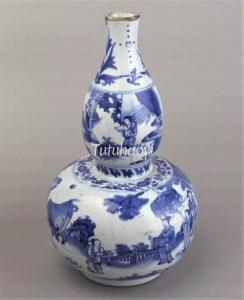

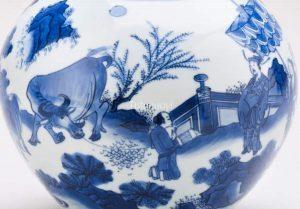

Fig 3-4: gourd-shaped porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, Jiajing period (1522–66), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum, Object Number: y1930-173

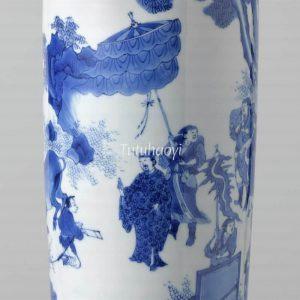

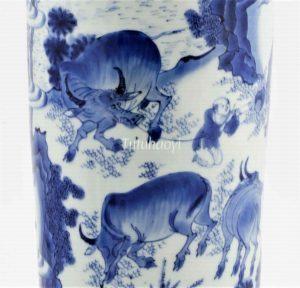

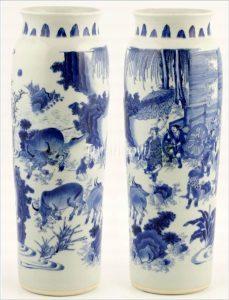

Fig 5-6: porcelain sleeve vase with underglaze blue decoration, Chongzhen period (1628–44), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fig 7-8: porcelain sleeve vase with underglaze blue decoration, Chongzhen period (1628–44), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Sir Michael Butler Collection

Fig 9-10: porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, Chongzhen period (1628–44), courtesy of The Royal Collection Trust, UK, RCIN 1402