Wu Song Slaying the Tiger

武松打虎

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

Nicknamed xingzhe (行者), ‘Pilgrim’ or ‘Traveller’, Wu Song (武松) is a popular fictional figure well-known for his slaying a tiger single-handedly after he was intoxicated on local rice wine. His heroic deed was first recorded as a title of a play in The Register of Ghosts (录鬼簿 Lugui bu), compiled by Zhong Sicheng (钟嗣成 ca 1279 – ca 1360). The book is a bio-bibliography of dramas and dramatists and lists the play entitled Wu Song Slaying a Tiger Even After His Quarterstaff Was Broken (折担儿武松打虎). During the sixteenth century, the legendary tiger-slaying episode was adopted in Shen Jing’s (沈璟, 1553–1610) miraculous play (传奇 chuanqi) The Story of the Righteous Knight-Errant (义俠记 Yi Xia Ji) and the two great classical novels in Chinese literature, i.e. The Water Margin (水浒传 Shui Hu Zhuan) and The Plum in the Golden Vase (金瓶梅 Jin Ping Mei).

During a trip, Wu Song entered a tavern at the foot of Jingyang Ridge (景阳冈), to have a break. The shop owner was proud of the potency of his alcoholic beverage and warned his customers not to drink more than three bowls and go alone to the territory of a man-hunting tiger in the mountains. Wu Song ignored his advice and proceeded with his journey even after drinking eighteen bowls of the rice wine. Sure enough, in the bushes, Wu Song was ambushed by the hungry tiger and shock out of his stupor. After an arduous primaeval confrontation between man and nature, Wu Song subdued the mighty beast. On his way out, Wu Song met some local hunters who had been trying to eliminate the monster and they treated him with awe and respect. His Gilgamesh-like feat won him the honour of being the local hero and the story passed on everybody’s lips with numerous adaptations in arts.

Read Dr Yibin Ni’s blog here to see how this story scene became the historical evidence of a harbinger of the future globalisation.

Other story scenes related to the tiger:

Li Cunxiao Slaying a Tiger 李存孝打虎

Yang Xiang Trying to Throttle the Tiger to Rescue Her Father 杨香扼虎救亲

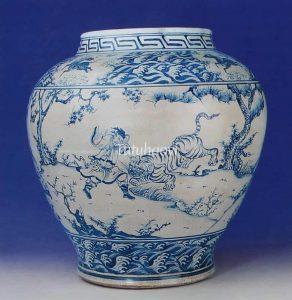

Fig 1: porcelain jar with underglaze blue decoration, mid-15th century, courtesy of Christie’s Auction House, Hong Kong, 1997

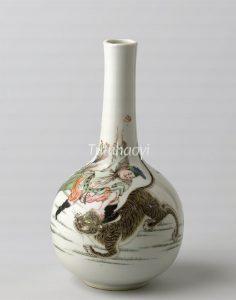

Fig 2: porcelain bottle vase with overglaze enamelled decoration, first quarter of the 18th century, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fig 3: set of four teabowls and saucers, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Cohen & Cohen, Chinese Export Porcelain and Oriental Art (Tyger Tyger!; November 2016)

Fig 4: porcelain oval dish with overglaze enamelled decoration, first quarter of the 18th century, courtesy of Cohen & Cohen, Chinese Export Porcelain and Oriental Art (Soldier, Soldier; October 2003)

Fig 5: fresco, Republic period (1911–49), the Long Corridor of the Summer Palace, Beijing