Hundred Children

百子图

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

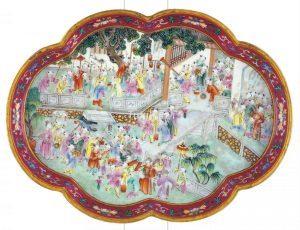

The Hundred Children motif (百子图) represents the most elaborate and auspicious extension of the broader Children at Play theme in traditional Chinese art. While both motifs depict scenes of children engaged in lively and joyful activities—such as kite-flying, lion dancing, and mimicking adult roles—the defining feature of the Hundred Children composition is its scale, narrative structure, and symbolic intensity.

Unlike smaller portrayals of a few children at play, Hundred Children scenes typically feature dozens of children—sometimes literally a hundred—engaged in coordinated yet playful acts, often within palace gardens or festive settings. These grand compositions became especially prominent in decorative arts of the Ming and Qing dynasties, appearing on porcelain, lacquerware, silk tapestries, and marriage furnishings.

The motif draws inspiration from a legendary tale recorded in Liexian Zhuan (列仙传), a Han dynasty compilation of biographies of immortals, which states: ‘King Wen of Zhou had a hundred sons, all of whom attained immortality’ (周文王有百子,皆得仙道). This idea was echoed in later encyclopaedic works such as the Taiping Yulan (太平御览), which further emphasised the symbolic connection between King Wen’s lineage and idealised prosperity: ‘Seventy of them served as ministers’ (七十子受命为卿士). Though not historically factual, this legend became a powerful emblem of dynastic flourishing and ancestral abundance.

In this context, the Hundred Children motif came to embody not merely the charm of childhood, but the Confucian aspiration for a thriving lineage, continuity of family virtues, and multigenerational harmony.

scene description by Rachel Ma

Related Motifs & Symbols

Grape 葡萄

May the male line in your family clan continue and flourish (pictorial allusion) 瓜瓞绵绵

May you have as many male offspring as a pomegranate has seeds 榴开百子

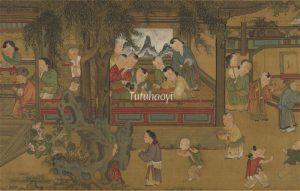

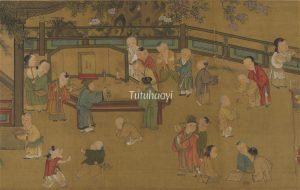

Fig 1-3: Bai Zi Huan Ge Tu 百子欢歌图, hand scroll, ink and colour on paper, Su Hanchen, Song dynasty (960–1279), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 4-5: round ink-cake (front and the reverse), Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

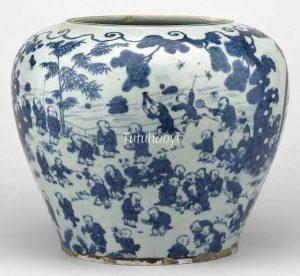

Fig 6: porcelain jar with underglaze blue decoration, 16th century, Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

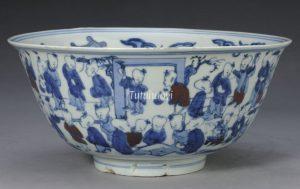

Fig 7: porcelain bowl with underglaze cobalt-blue and copper-red decoration, Wanli period (1572–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

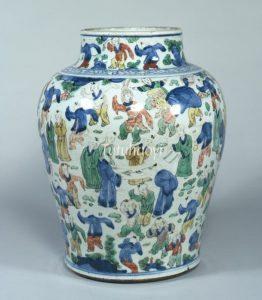

Fig 8: porcelain jar with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, 16th -17th century, courtesy of Tokyo National Museum, Japan

Fig 9: round porcelain box with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, 17th century, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

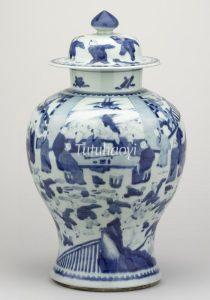

Fig 10: lidded baluster jar with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 11: baluster jar with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Shenyang Museum, Liaoning Province, China; Photograph by Rachel Ma

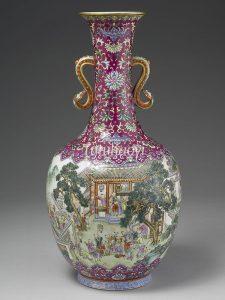

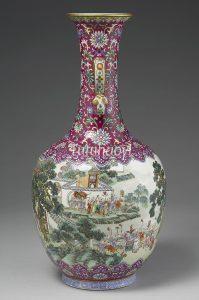

Fig 12-13: famille rose porcelain vase, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 14: famille rose porcelain vase, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Shanghai Museum, China; Photograph by Rachel Ma

Fig 15: famille rose porcelain saucer, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 16: famille rose lantern-shaped vase, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Nanjing Museum, Jiangsu Province, China; Photograph by Rachel Ma

Fig 17: famille rose porcelain bowl, Jiaqing period (1796–1820), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei