May the length of your life be eternally prolonged!

海屋添筹

© Tutuhaoyi.com owns the copyright of the description content for the images attached. Quoting all or part of the description content on this page is permitted ONLY IF ‘Tutuhaoyi.com’ is clearly acknowledged anywhere your quote is produced unless stated otherwise. (本页描述内容版权归Tutuhaoyi.com所有,转发或引用需注明 “Tutuhaoyi.com”, 侵权必究, 已注开源信息的条目除外。)

In this scene, there are several Chinese longevity symbols such as the crane, the generic immortal, the pine tree, and the deer, etc. However, the proper meaning of this particular scene is not a simple assemblage of individual symbols. It is a snapshot of a coherent narrative that has been well-loved and widely consumed in the visual oeuvre that represents the Chinese longevity ideal.

The literary origin of the scene can be traced back to an anecdote collected in Notes by Dongpo (东坡志林), compiled by a prominent man of letters of the Song dynasty, Su Shi (苏轼, 1037-1101). During one chance meeting of three geriatric men, the topic of age was broached. Each one of them tried their best to exaggerate his own great age. The second speaker famously boasted, ‘After every cycle of the sea drying up and becoming mulberry fields, I put a strip of bamboo in my house as a counter and now the strips have already filled ten of the rooms.’ Later, this dramatic detail evolved into a classic allusion to longevity, a popular dream cherished by all people in China. Pictorial representations of this dramatic moment were invented and elaborated into different versions to adorn birthday presents of all kinds.

Initially, the title of the scene is, literally: ‘A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea (海屋添筹 hai wu tian chou)’. The first two characters of the phrase resulted from compressing the paragraph spoken by the second speaker in the story into an abbreviation consisting of the first and the last characters 海屋 hai wu (‘海水变桑田时, 吾辄下一筹, 尔来吾筹已满十间屋’). The coined two-character phrase ‘海屋 hai wu’ now means a ‘pavilion at sea’, serving as the first two characters in the set phrase. The rest two characters of the phrase ‘添筹 tianchou’ denotes the action (of a crane) adding a bamboo strip as a counter’. Thus, the four-character phrase alludes to the second speaker’s words in the original story.

During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), pun rebus designs became more and more popular in folk decorative arts. The last character of the phrase ‘筹 chou’ for ‘bamboo strip counter’, acquired a pun on ‘寿 shou’, the Chinese character for ‘longevity’. Then, the phrase virtually conveys the meaning of a birthday wish: ‘May the length of your life be eternally prolonged (海屋添寿 hai wu tian shou)’. One of the earliest mentions of this pun phrase in literature can be found in Section 22 in the second part of the book Tao Ya (匋雅), or ‘Notes of Chinese Best Pottery and Porcelain’, compiled by Chen Liu (陈浏) and published in 1910.

This research article is written by Dr Yibin Ni.

Literature:

- Jeffrey P. Stamen and Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni, A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection: Jieruitang Publishing, Bruges, 2017, p. 84-85.

- 倪亦斌:《仙鹤寿桃祝寿碗 暗藏海屋添筹图》,《读者欣赏》,兰州:读者出版传媒股份有限公司,2018-01,110-117 页

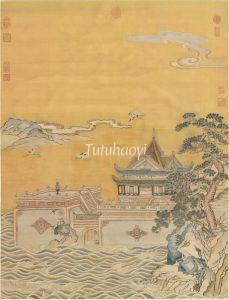

Fig 1: silk fabric hanging scroll, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 2: jade container, Ming dynasty (1368–1644), courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

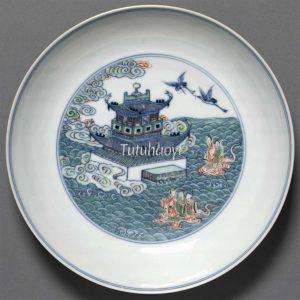

Fig 3: porcelain dish with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662-1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Jie Rui Tang Collection

Fig 4: porcelain dish with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662-1722), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 5: porcelain flower pot, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

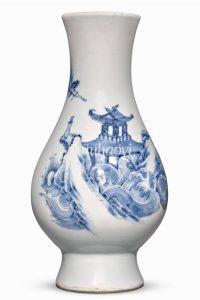

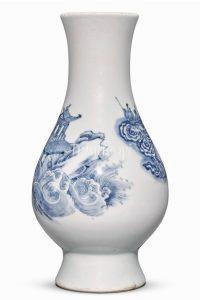

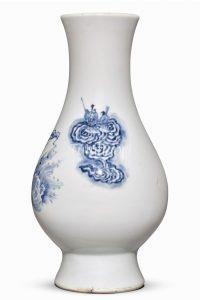

Fig 6-8: porcelain beaker vase, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Sotheby’s Auction House New York, 23 March 2022, Lot 332

Fig 9: porcelain bowl, Kangxi period (1662–1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow

Fig 10: porcelain dish with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, Yongzheng period (1723–35), courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Fig 11: porcelain dish with underglaze blue and overglaze enamelled decoration, Yongzheng period (1723–35), courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington

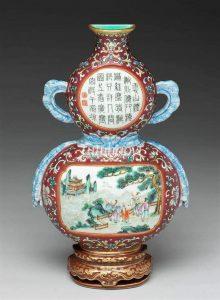

Fig 12: famille rose vase, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Fig 13: doucai porcelain dish, Qianlong period (1736–95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Beijing Art Museum, China

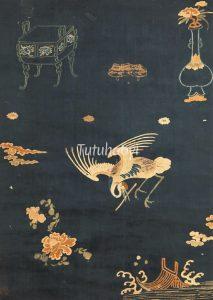

Fig 14: textile fabric, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Tianjin Museum, China

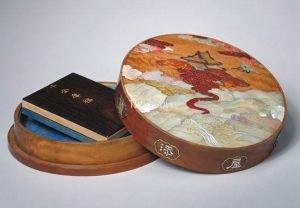

Fig 15: wooden lidded box, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 16: blue-and-white porcelain dish, 1780, courtesy of Princessehof Ceramics Museum, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands

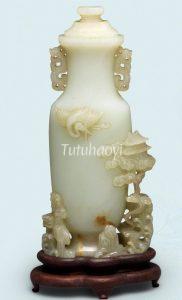

Fig 17: jade vase, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

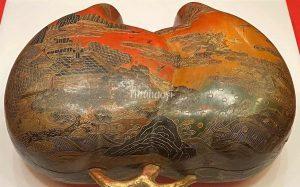

Fig 18: lacquered wooden container, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

Fig 19: kesi silk fabric fan, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

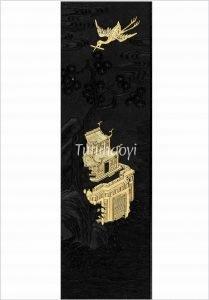

Fig 20: ink stick, Guangxu period (1875–1908), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing