More often than not, traditional Chinese motifs or symbols are not receiving their deserved attention, being given simplistic or inadequate labels and inaccurate explanations in our museums, catalogues, or even scholarly writing. The treatment of many pictorial representations of the thousand-year-old literary anecdote ‘A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea (海屋添筹 hai wu tian chou)’ is a case in point.

The literary origin of the scene can be traced back to an anecdote collected in Notes by Dongpo (东坡志林), compiled by a prominent man of letters of the Song dynasty, Su Shi (苏轼, 1037-1101). During one chance meeting of three geriatric men, the topic of age was broached. Each one of them tried their best to exaggerate his own great age. The second speaker famously boasted, ‘After every cycle of the sea drying up and becoming mulberry fields, I put a strip of bamboo in my house as a counter and now the strips have already filled ten of the rooms.’ Later, this dramatic detail evolved into a classic allusion to longevity, a popular dream cherished by all people in China. Pictorial representations of this dramatic moment were invented and elaborated into different versions to adorn birthday presents of all kinds.

Initially, the title of the scene is, literally: ‘A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea (海屋添筹 hai wu tian chou)’. The first two characters of the phrase resulted from compressing the paragraph spoken by the second speaker in the story into an abbreviation consisting of the first and the last characters 海屋 hai wu (‘海水变桑田时, 吾辄下一筹, 尔来吾筹已满十间屋’). The coined two-character phrase ‘海屋 hai wu’ now means a ‘pavilion at sea’, serving as the first two characters in the set phrase. The rest two characters of the phrase ‘添筹 tianchou’ denotes the action (of a crane) adding a bamboo strip as a counter’. Thus, the four-character phrase alludes to the second speaker’s words in the original story.

The textual origin of this compressed phrase can be traced back to the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). The Complete Collection of Nondramatic Songs in the Yuan Dynasty (全元散曲) has recorded a song entitled ‘A Sprig of Flowers – A Birthday Boy of Eighty Years Old (一枝花·寿人八十)’ by the poet Shen Xi (沈禧, ?-?), which contains the line ‘海屋筹添数倍增 (A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea and the life span will increase by multiples)’, albeit with the last two characters of the phrase in reverse order. In the following Ming dynasty (1369-1644), Li Kaixian (李开先, 1502-68) used the phrase in a line in the second act of his first play The Story of Lin Chong’s Sword (林冲宝剑记), which says, ‘欣逢日吉时良,海屋添筹,南山寿祝无疆 (Happily we encounter the lucky times. A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea and our life span will be as long as the South Mountains without limit)’.

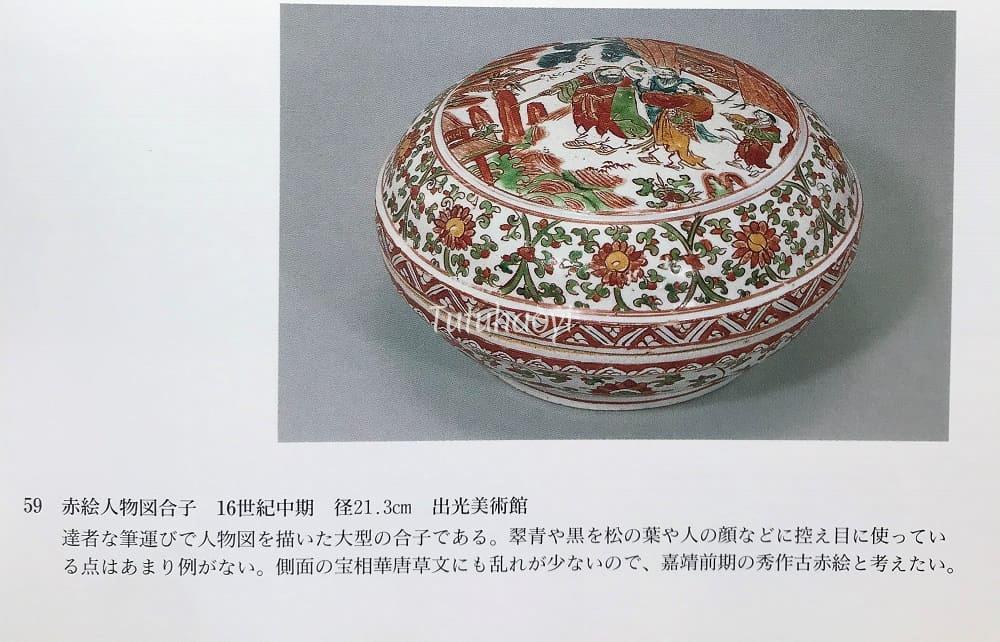

One of the earliest extant examples of this scene is in the collection of Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo, Japan and published in Ming Red Ware Designs (明の赤绘), written by Ryoichi Fujioka (藤冈 了一) in 1972 and in Ming Five-Colour Enamelled Wares (明の五彩) written by Ritsuko Yajima (矢島 律子) in 1996. It appears on a rare mid-16th-century round covered porcelain box with enamelled decoration. Regrettably, the fascinating painting on its cover has not been given any explanation in either of the book. 24 years later, Professor Yajima added only a point of how skillfully the figure painting was executed but there was still no mention of its subject matter.

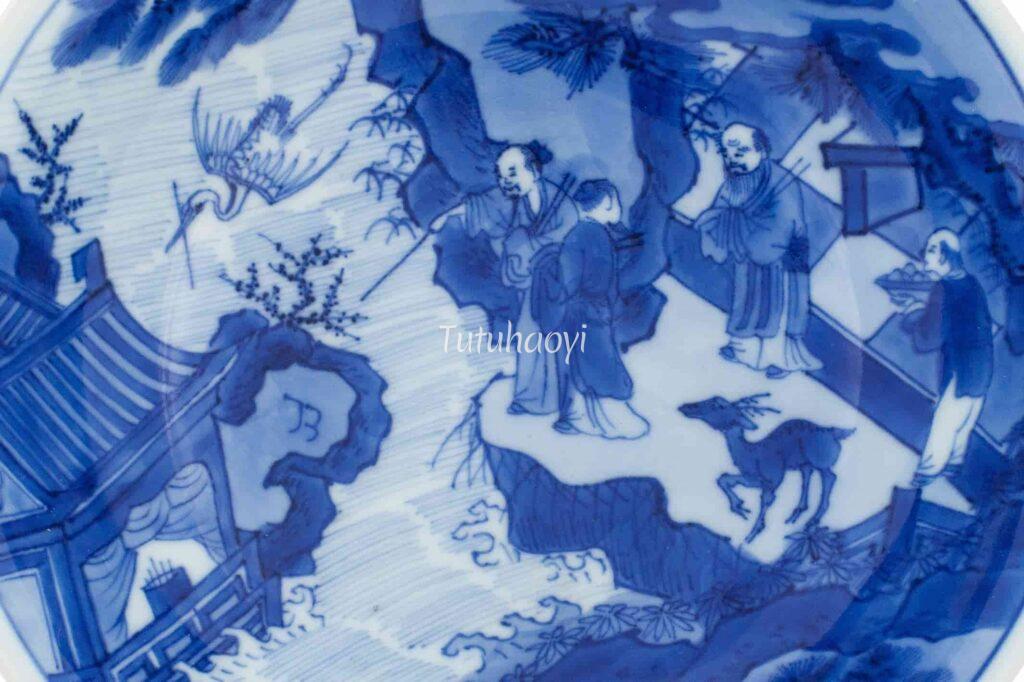

In the centre of the scene stand three old men, one of whom is holding a long bamboo strip in his right hand, talking to his companions. Presumably, he is the man who is boasting his stock of ten roomfuls of strips. Above his right arm, a crane is hovering in the air, carrying a strip in its beak. Next to them on the left, we can see three peaks rising from the wavy sea and a corner of some roofs and pillars of a building. Pictorially, the pictorial elements of old men, a crane with a strip in its beak, and some architecture in the sea are important for the representation of the literary phrase ‘A bamboo counter is being added to the house in the sea (海屋添筹 hai wu tian chou)’. As is the case in language use or other information transmission, these original essential elements can undergo changes such as elaboration, omission, or abbreviation as the creators of the scene see fit.

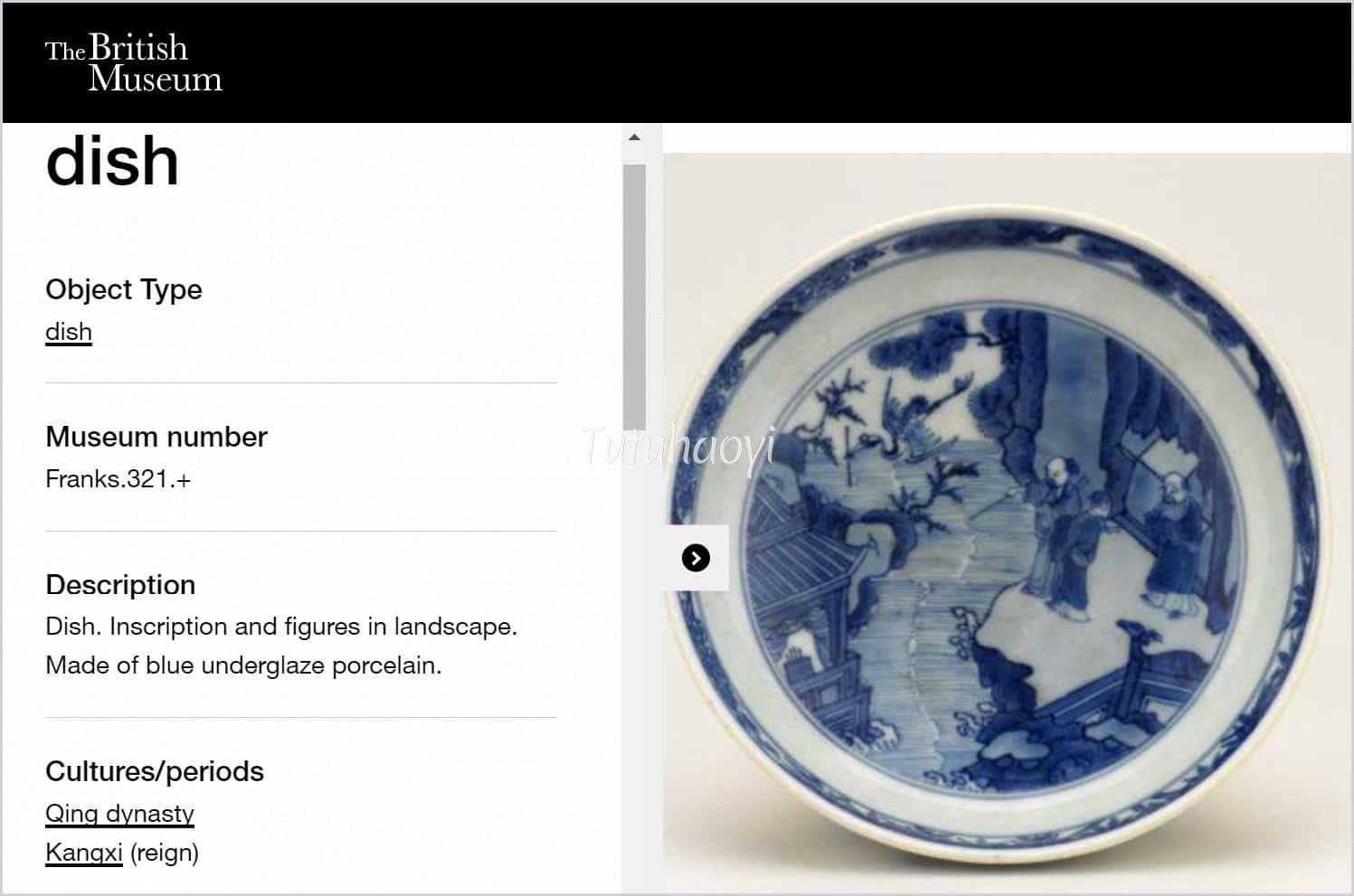

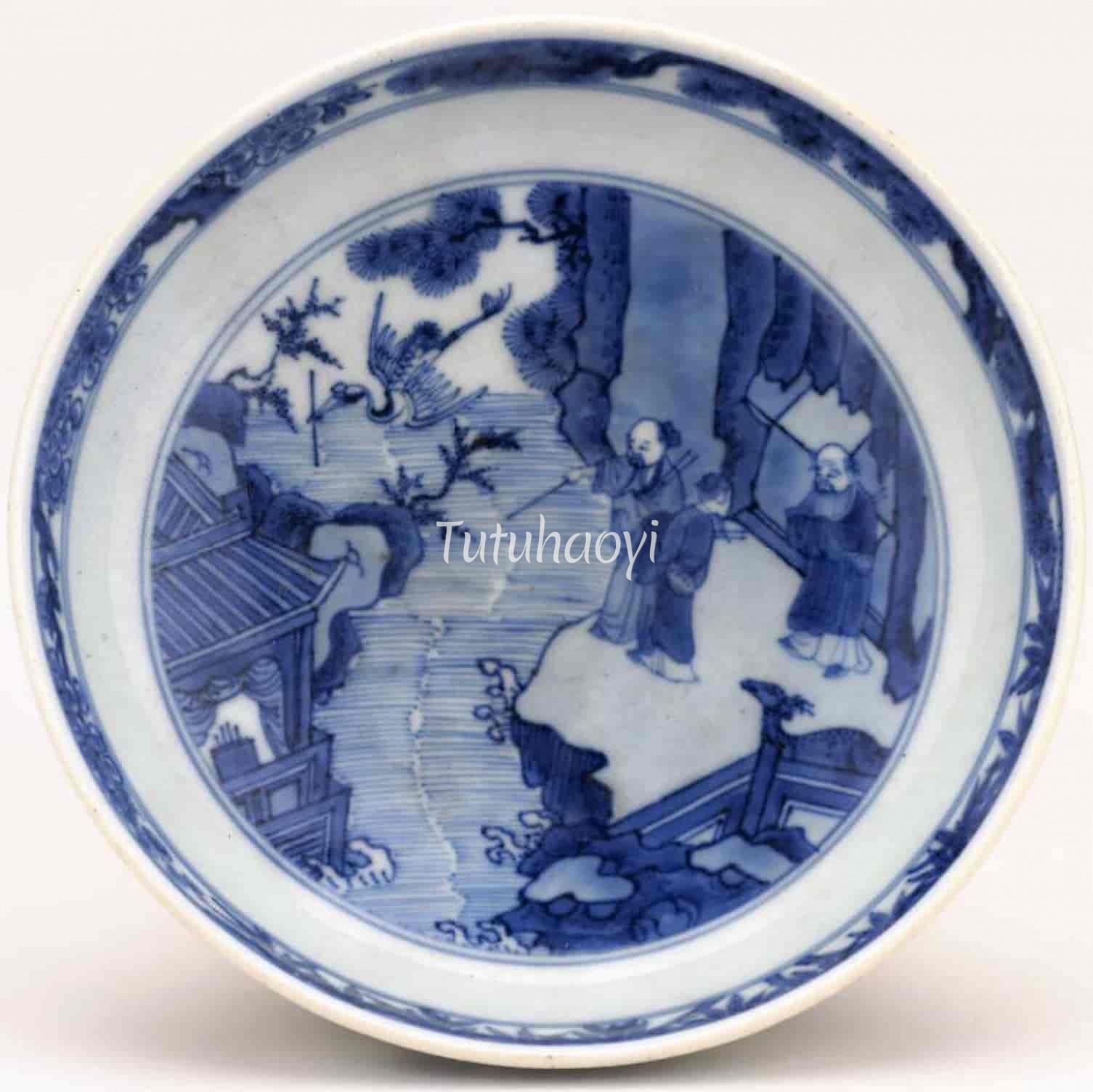

The description found in the online catalogue of the British Museum for a Kangxi blue-and-white dish with a less glamourous version of the same scene is ‘figures in landscape’. This is not much improvement compared to Mr Fujioka’s silent treatment of the matter in his book.

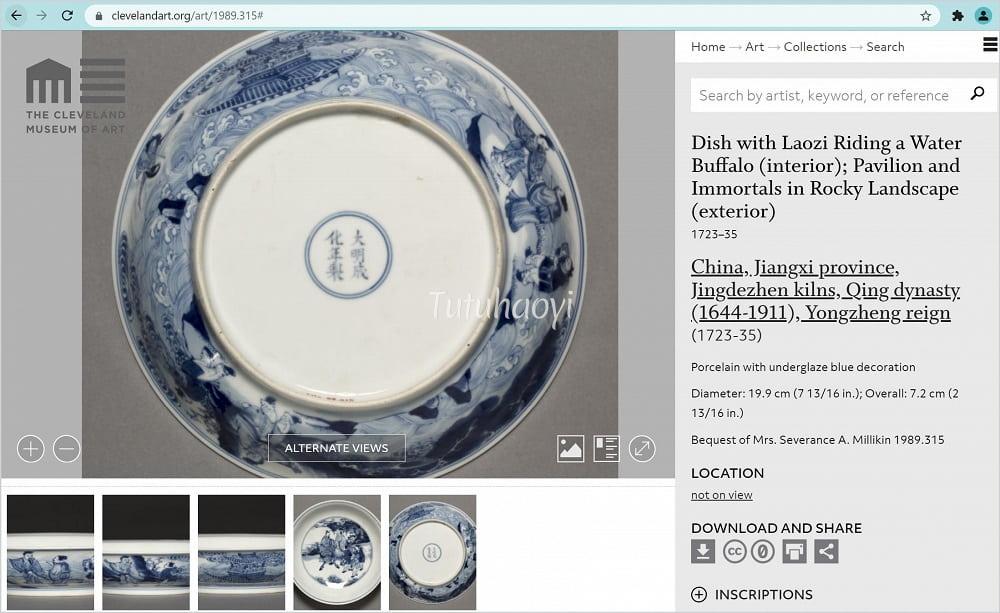

There is a Yongzheng blue-and-white dish in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, USA. Its exterior is adorned with a slightly more elaborated version of this scene, with old men, pavilion in the sea, and the crane intact and some additional servants away from the essential elements. The museum catalogue describes them as ‘Pavilion and Immortals in Rocky Landscape’. The writer has given a true description of the scene but is unaware of its literary subject matter.

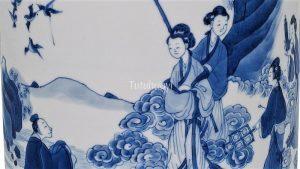

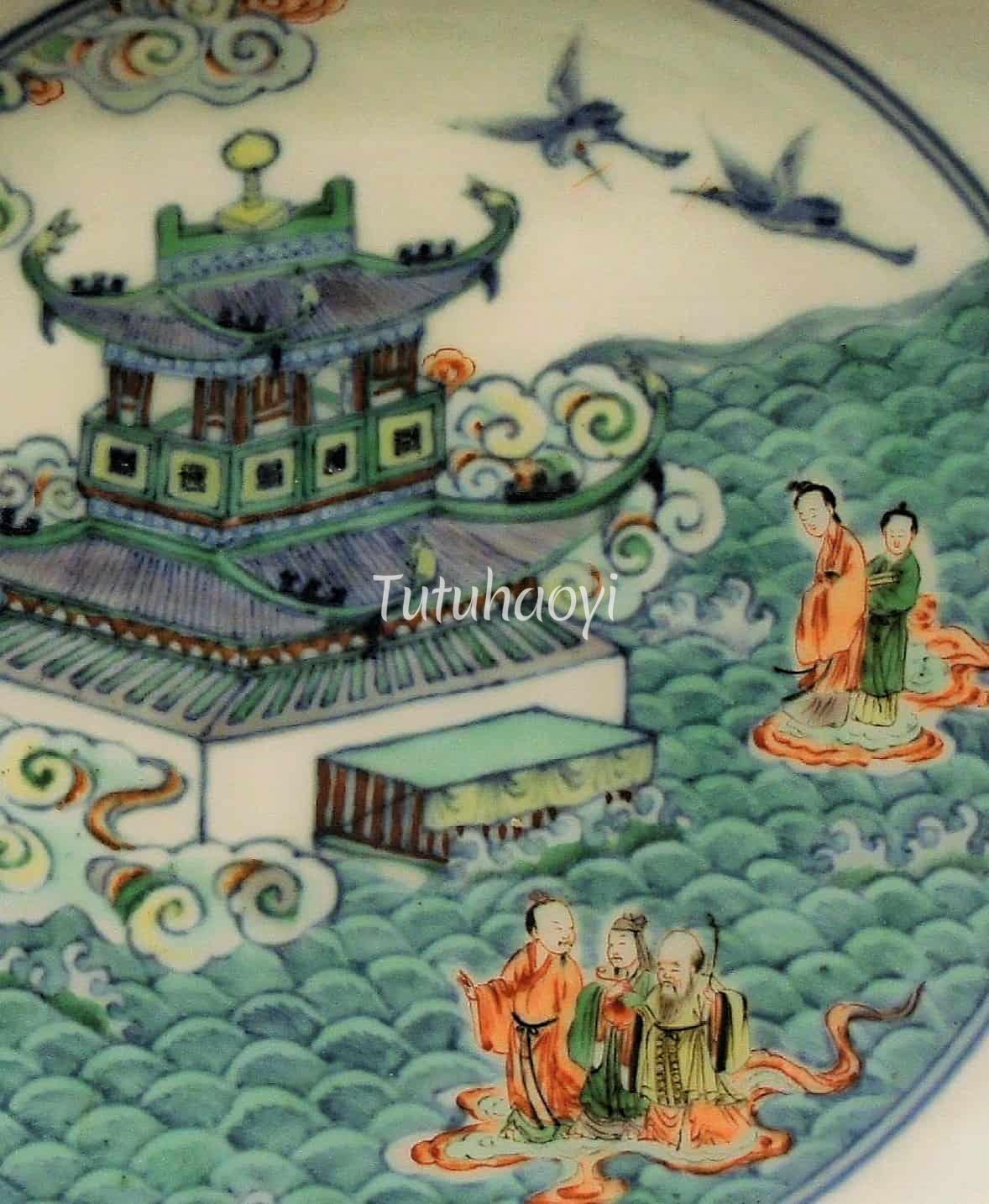

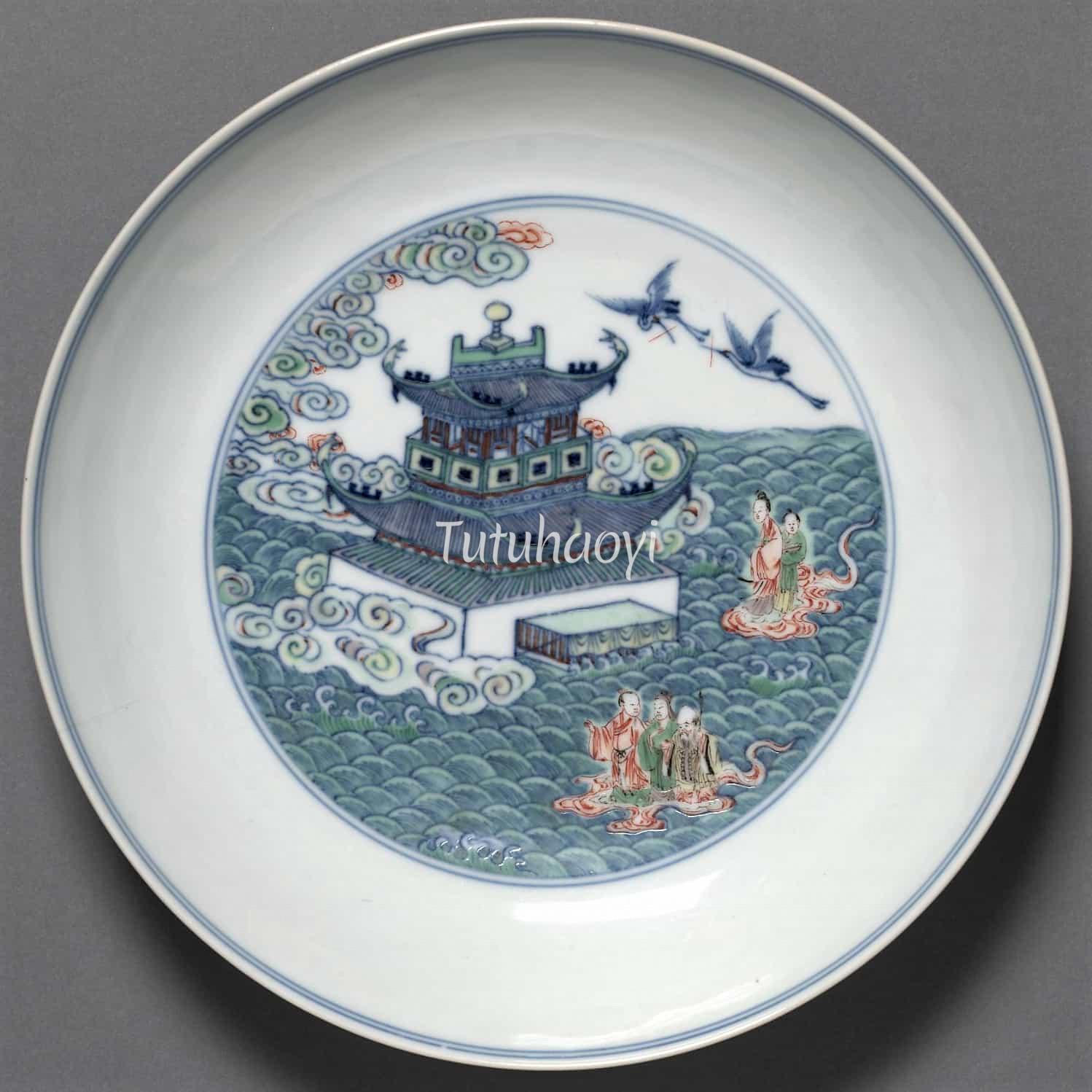

In the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA, there is a Yongzheng dish with a slightly different version of the scene. It is decorated with the technique known as ‘doucai 斗彩’, i.e., with underglaze blue and overglaze enamels. The essential elements of the pavilion in the sea (海屋 hai wu) and the crane carrying a strip (添筹 tianchou) are both depicted. But the three old men are missing. Instead, there are one group of well-dressed men including a bald one looking like the Star God of Longevity (寿星 shouxing) and another group of two women, one of whom is a maid. They are riding on clouds and, therefore, are immortals and fairies, who are usually associated with the longevity cult. There is no mention of the meaning of the scene in the museum’s online catalogue. Nor is there in The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue: Decorative Arts, Part II – Far Eastern Ceramics and Paintings, in which the bowl is shown and discussed (Bower, Virginia, Josephine Hadley Knapp, Stephen Little, & Robert Wilson Torchia, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1998, p. 227).

In the book Daoism in the Arts of China (Stephen Little, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), a doucai dish in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, which looks similar to the National Gallery dish quoted above, is given the following explanation: ‘At the center of this dish is a roundel depicting a Daoist paradise, surrounded by clouds and rolling waves. In the foreground, three male deities are shown crossing the waves on a cloud. The cranes flying in the air also symbolize longevity. The symbolism of the dish expresses the wish for good fortune and longevity, and it is possible this and similar dishes were designed for an imperial birthday’ (p. 45, Pl. 18).

In the light of the literary anecdote told above and its existing pictorial representations such as the 16th-century box in the Japanese book and the 18th-century Cleveland blue-and-white dish, we know that what is called ‘Daoist paradise’ is actually the house into which the crane is putting strip counters. Also, the essential role of the crane with a strip in its beak is to add strips to the house, as is clear in the original story and its earlier pictorial representations.

The online catalogue of the Cleveland Museum of Art now describes the same Yongzheng doucai dish as ‘Isle of the Immortals’, a phrase somewhat close to ‘Daoist paradise’ in the book Daoism in the Arts of China.

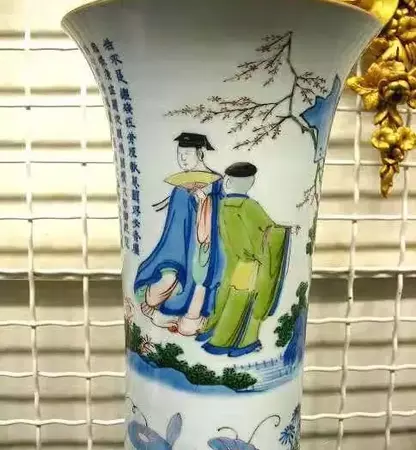

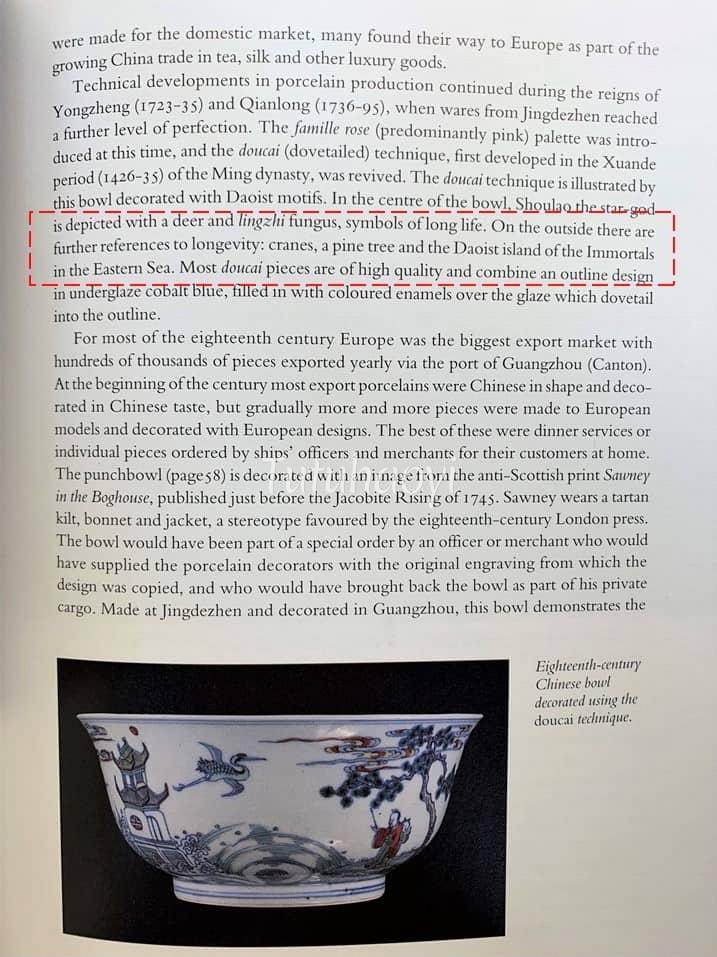

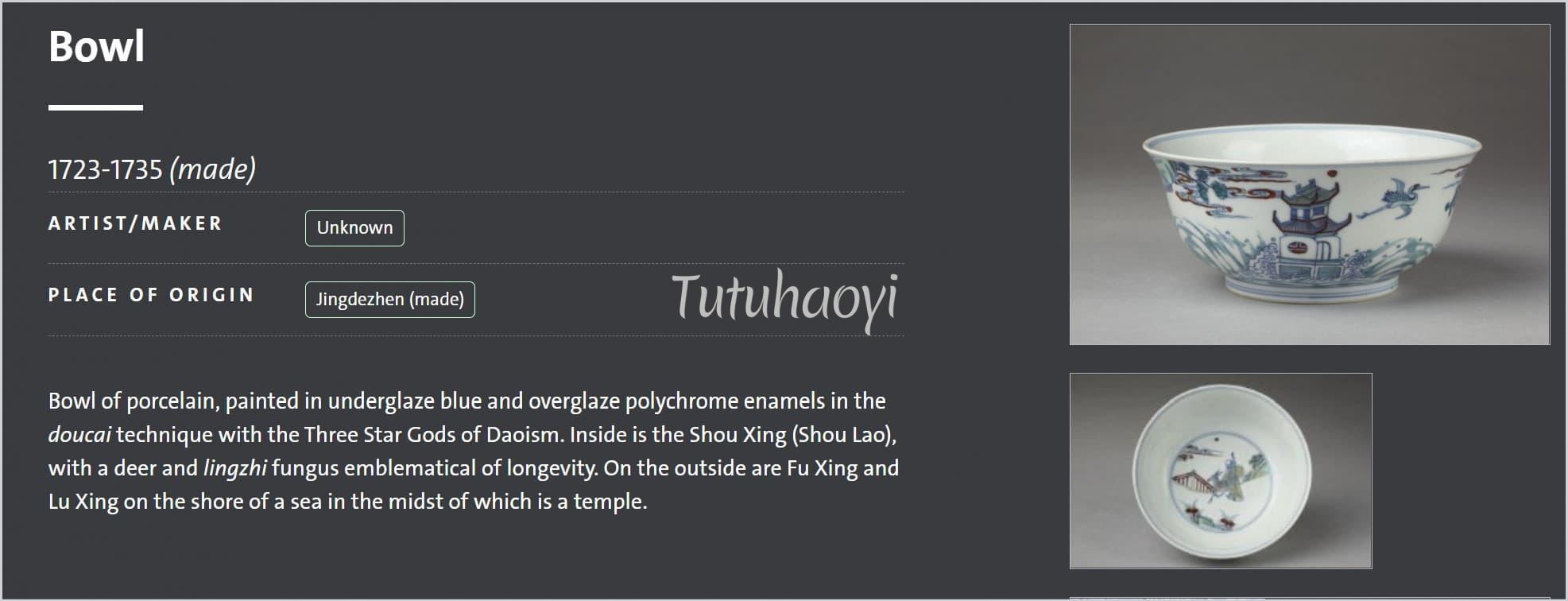

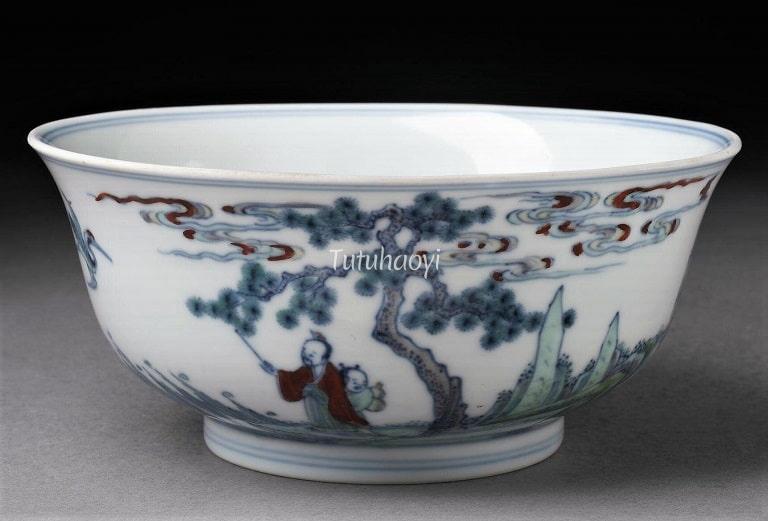

In Chinese Art and Design (Rose Kerr ed., Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1991), a doucai bowl with the same scene has the following explanation: ‘On the outside there are further references to longevity: cranes, a pine tree and the Daoist island of the Immortals in the Eastern Sea.’

In fact, this is a slightly different variation of the scene. We can see an old man in a green gown and a red cloak standing under the pine tree, holding out a bamboo strip, with his boy attendant closely behind him. A crane is flying towards him as if it were to fetch the strip. In a typical version of the scene, the crane is carrying a strip in its beak and flying towards the pavilion at sea. In the current V&A Museum online catalogue, the description of the same scene on the same bowl is ‘On the outside are Fu Xing and Lu Xing on the shore of a sea in the midst of which is a temple.’ Apparently, the old man holding the bamboo strip counter can be neither Fu Xing, nor Lu Xing, the two Star Gods who supposedly bring you great good fortune and ample emoluments.

The same book also contains a late-Qing slate table screen bearing this scene and describes its meaning as follows: ‘The scene shows pavilions on the Islands of the Immortals, a magic paradise land in the Eastern Sea. Two cranes fly out of the clouds and these birds together with the evergreen pine trees growing on the island traditionally bear wishes for a long life, something to which all Chinese aspired and which also had implications for the continuation of the family line’ (p.122, Pl. 48).

Similar to Dr Little’s description, the claim of ‘pavilions on the Islands of the Immortals, a magic paradise land in the Eastern Sea’ has no evidence in literature and the true role of the cranes in this scene is also overlooked. Currently, the description of the table screen in the online catalogue of the V&A Museum has remained the same as that in the book Chinese Art and Design published in 1991.

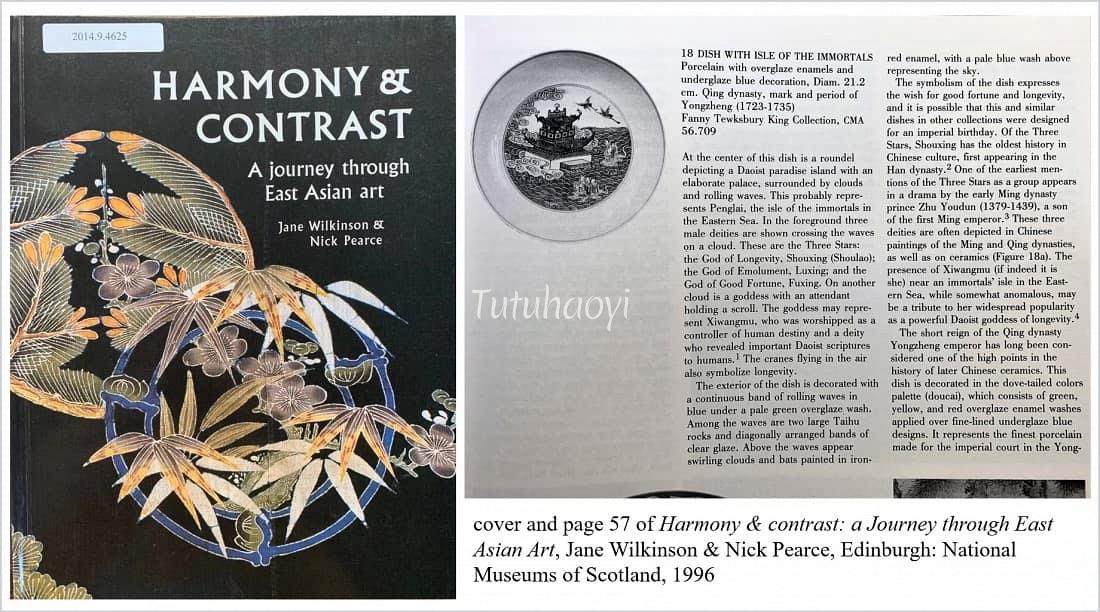

Another Yongzheng doucai dish, similar to the National Gallery dish quoted above, published in Harmony & contrast: a Journey through East Asian Art (Jane Wilkinson & Nick Pearce, Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 1996, p. 57), is called ‘Dish with Isle of Immortals’. The author’s description of the scene on the dish is ‘… depicting a Daoist paradise island with an elaborate palace, surrounded by clouds and rolling waves. This probably represents Penglai, the isle of the immortals in the Eastern Sea. …The cranes flying in the air symbolize longevity’. For this particular scene, ‘Daoist paradise island’, ‘isle of the immortals in the Eastern Sea’, and ‘cranes flying in the air symbolize longevity’ are all inaccurate descriptions used by the two authors quoted above.

There is still another line of explanation for this scene, usually for a group of blue-and-white dishes or shallow bowls with a six-character ‘大清康熙年制 da qing kang xi nian zhi’ reign mark inside their foot rings. In the catalogue of Transitional Wares for the Japanese and Domestic Markets, published by Marchant, London in 1989, we find the following explanation for the scene on the Kangxi blue-and-white shallow bowl (cat. no. 49): ‘painted with Shoulao, two companions and his deer attended by a servant on a rocky ledge, watching a crane flying with joss-sticks in its beak to a temple in the waves’.

When the same shallow bowl was sold by Sotheby’s New York in 2018, not much improvement can be seen in the catalogue entry. It reads: ‘with three immortals accompanied by an attendant bearing peaches, all on a rocky ledge framed by pines, and clouds, a crane carrying lengths of bamboo in its beak to a pavilion floating on the waves below’.

The whole is often greater than the sum of the parts. We may realise by now that the proper meaning of this particular scene is not a simple assemblage of individual symbols. It is a snapshot of a coherent narrative that has been well-loved and widely consumed in the visual oeuvre that represents the Chinese longevity ideal.

During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), pun rebus designs became more and more popular in folk decorative arts. The last character of the phrase ‘筹 chou’ for ‘bamboo strip counter’, acquired a pun on ‘寿 shou’, the Chinese character for ‘longevity’. Then, the phrase virtually conveys the meaning of a birthday wish: ‘May the length of your life be eternally prolonged (海屋添寿 hai wu tian shou)’. One of the earliest mentions of this pun phrase in literature can be found in Section 22 in the second part of the book Tao Ya (匋雅), or ‘Notes of Chinese Best Pottery and Porcelain’, compiled by Chen Liu (陈浏) and published in 1910.

featured image of this article: porcelain dish (detail) with underglaze blue decoration, Kangxi period (1662-1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Jie Rui Tang Collection

Literature:

- Jeffrey P. Stamen and Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni, A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection: Jieruitang Publishing, Bruges, 2017, pp. 84-85.

- 倪亦斌:《仙鹤寿桃祝寿碗 暗藏海屋添筹图》,《读者欣赏》, 兰州: 读者出版传媒股份有限公司, 2018-01, 110-117 页

The findings and opinions in this research article have been written by Dr Yibin Ni.