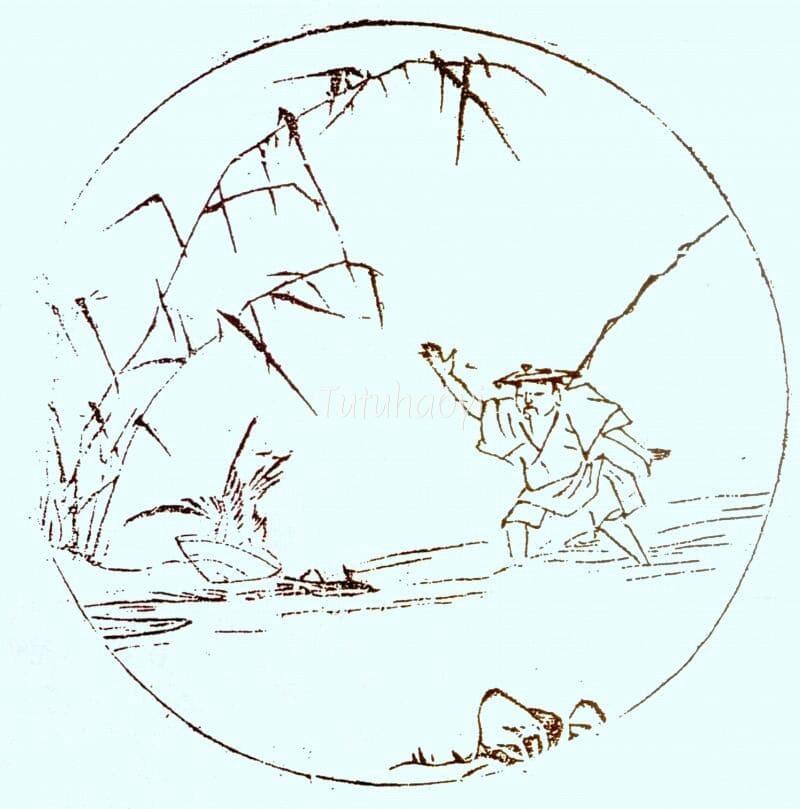

Editor: People who are not familiar with Chinese history and parables may have the impression that the above image is a genre painting of a fisherman’s daily life. But in fact, there is more meaning to it. Dr Yibin Ni will explain the story in detail and how this story scene has been presented in various forms of artworks.

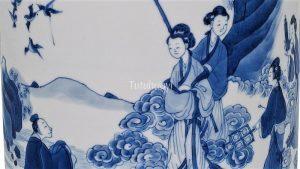

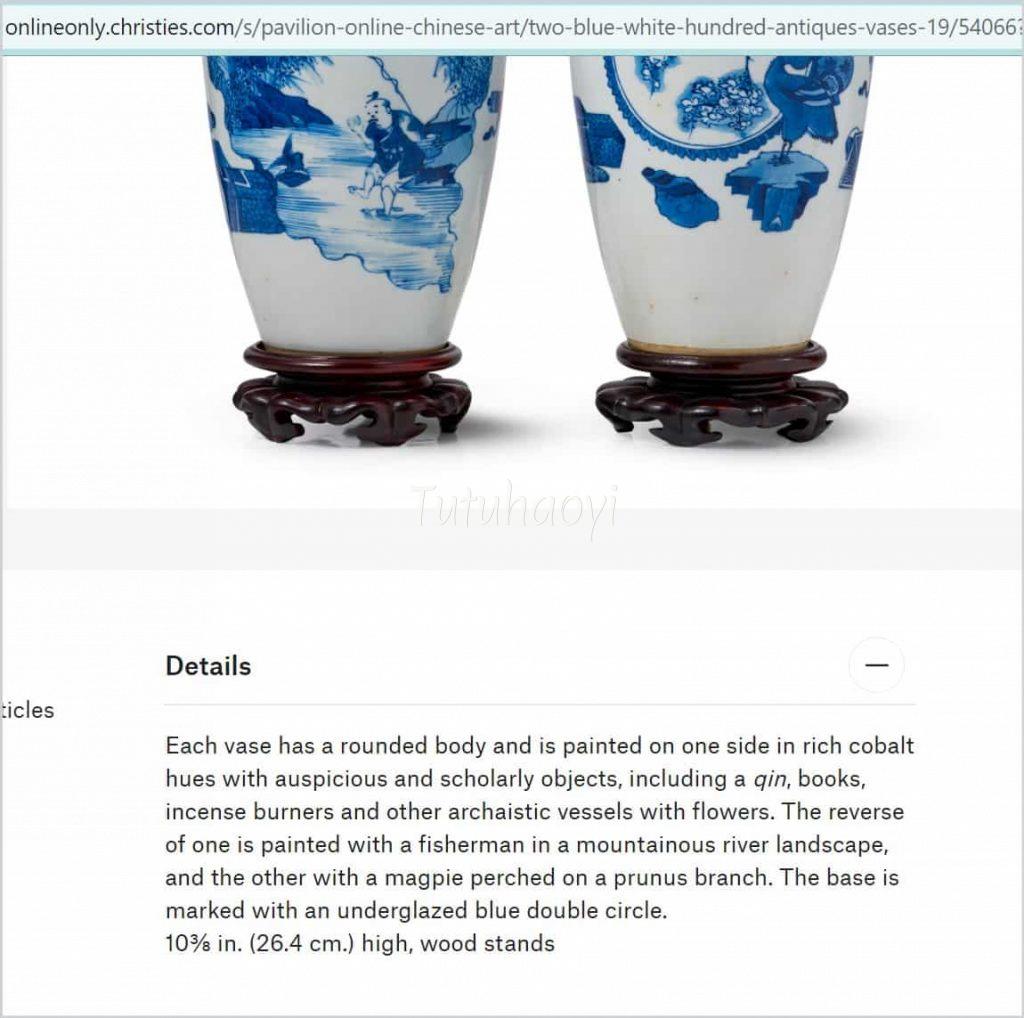

featured image above: porcelain bottle vase (detail), Kangxi period (1662-1722), Qing dynasty, courtesy of Christie’s online auction

The story scene above refers to an old Chinese saying: in the fight between the sandpiper and the clam, the fisherman has the best of it. This parable came from an ancient Chinese text entitled Strategies of the Warring States (战国策 Zhanguo Ce). The book contains anecdotes of diplomacy and warfare during the Warring States period (5th to 3rd centuries BC).

The State of Zhao (赵国) was planning to attack the State of Yan (燕国). Su Dai (苏代) was sent by the State of Yan to the State of Zhao to try to prevent the imminent calamity. During the audience that Su Dai had with King Huiwen of Zhao (趙惠文王, 310-266 BCE, r. 298-266 BCE), he found a clever way to persuade the king to change his mind. Here is Su Dai’s speech:

When I was leaving my country crossing the Yi River (in the present-day Yi County, Hebei province), I saw a clam lying open, enjoying the sunshine on the bank. Out of the blue, a sandpiper flew down and tried to snatch a morsel to eat between its shells. The clam promptly slammed its shells shut, locking the sandpiper’s beak in between. The sandpiper tried to wriggle out of the situation, saying, ‘If it doesn’t rain today and it doesn’t rain tomorrow, there will be a dead clam on the river bank.’ The clam retorted, ‘If I don’t let you go today and nor do I tomorrow, there will be a dead sandpiper on the river bank.’ While they grappled in a dead lock, a fisherman passed by and picked both up with very little effort. Now, if your majesty launched an attack on Yan, Yan would certainly try to resist your invasion. And the fight between the two countries would make both weak and then the State of Qin would be acting as that ‘fisherman’. I urge your majesty to reconsider your plan.

The king of Zhao got the message from Su’s story and called off the military campaign.

As a cautionary tale, this parable has been favoured by Chinese people for two millennia and has often been made into 2D or 3D images to educate the young.

During the second half of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the book printing industry flourished with the fast development of urban economy. Popular printing made it easy for more and more common people to possess and enjoy pictures in addition to texts as a way of disseminating information and knowledge. Images migrated to more and more different types of media, educational as well as entertaining. It is quite obvious that the printed picture of the parable that I have discovered and am presenting here influenced the artistic inspiration of the porcelain painters and opened a new world of resources for them. Otherwise, he would have been stuck with a very limited repertoire of pictorial motifs handed down in a strictly ‘master-to-apprentice’ manner.

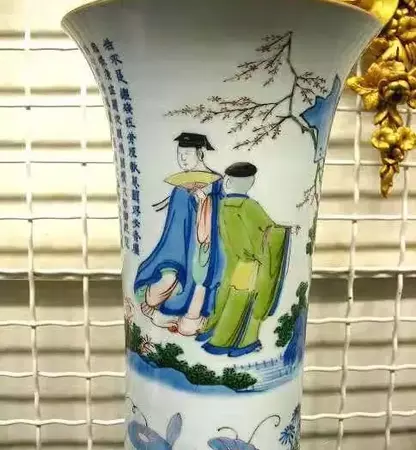

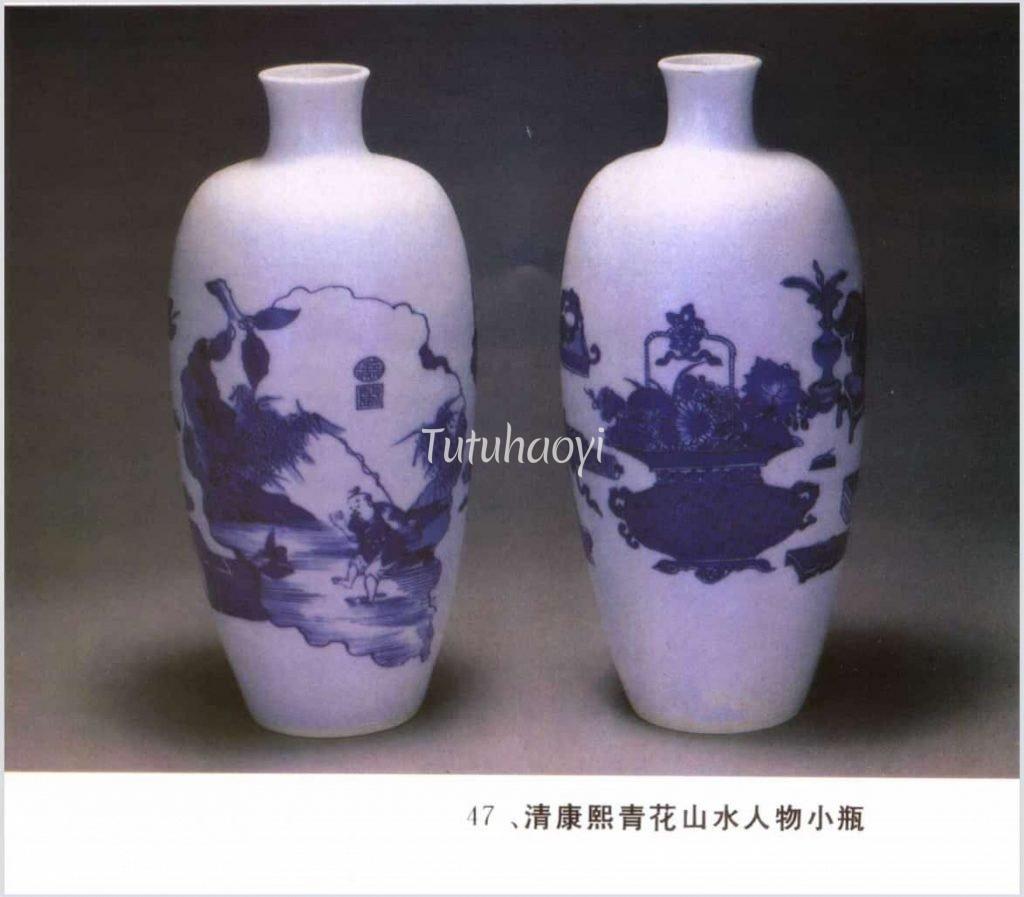

Examples of this image show that it was widely appreciated. However, the colossal disaster afflicted to the traditional Chinese culture has wiped out most of the precious memories. As a result, contemporary people, including many experts in the area, are indifferent to traditional scenes and motifs with rich cultural heritage. When the fine Kangxi blue-and-white bottle was published in an authoritative book on the authentication of Chinese ceramics, the description of the scene on the vase is merely ‘figures in the landscape’.

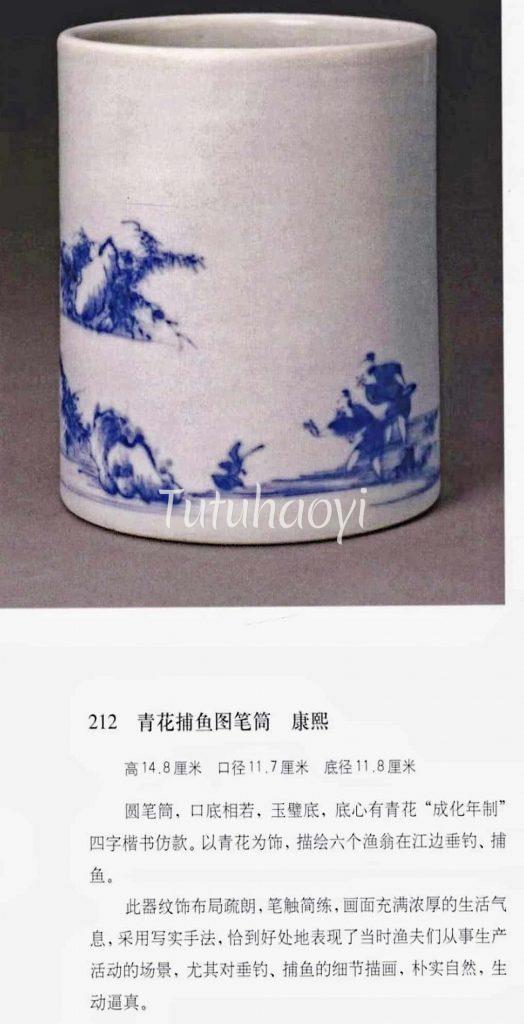

There is a Kangxi blue-and-white brush holder bearing a panoramic scene of fishermen’s activities in the Palace Museum, Beijing. Because of the popularity of the ‘sandpiper-and-clam’ story and its pictorial representation, the porcelain painter adapted it as part of the genre scene. In their description of the brush holder in their seminal volume of Blue-and-White Porcelains of the Shunzhi and Kangxi Reigns of the Qing Dynasty, 2005, the scholars in the Palace Museum mention only netting and angling, ignoring this culturally significant motif.

The description in the online catalogue of Christie’s auction house for Lot 19, 4-12 April, 2018, online auction 16321 is similarly vague: ‘a fisherman in a mountainous river landscape’.

By contrast, Bonhams online catalogue for a Yongzheng enamelled cup in Lot 29 in a sale in Hong Kong on 28 Nov 2017 has got the details right: ‘the second vividly depicting a fisherman wading in shallow water amidst a bamboo grove and rockwork with his arms outstretched forward in an attempt to catch a snipe and a clam.’

However, not every member of the English-speaking audience will get the ancient Chinese wisdom from this description. It could be a superb study case in contemporary business schools. Try to avoid such a zero-sum business competition: when the predator and the prey are fixated on their adversarial stubbornness, BOTH lose.

The findings and opinions in this research article have been written by Dr Yibin Ni.