Have you wondered why you often see an image of a man lying or ‘dancing’ beside a large fish on Chinese antiques? Is it referring to some specific figure and story in ancient China? Here is Dr Yibin Ni explaining to us the meaning of this touching story that reveals the traditional Chinese virtue of filial piety.

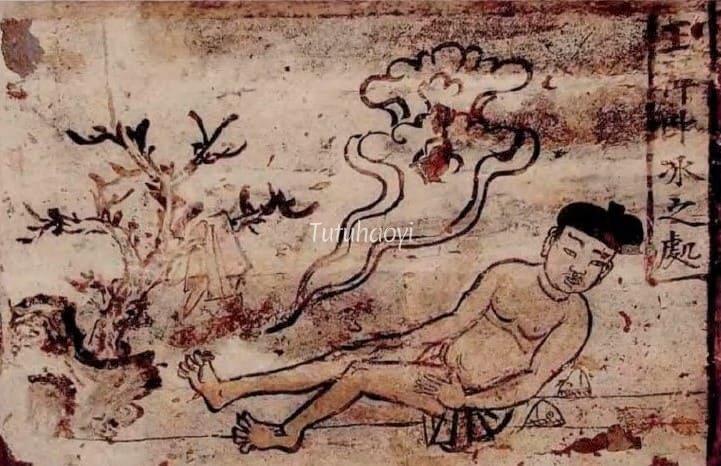

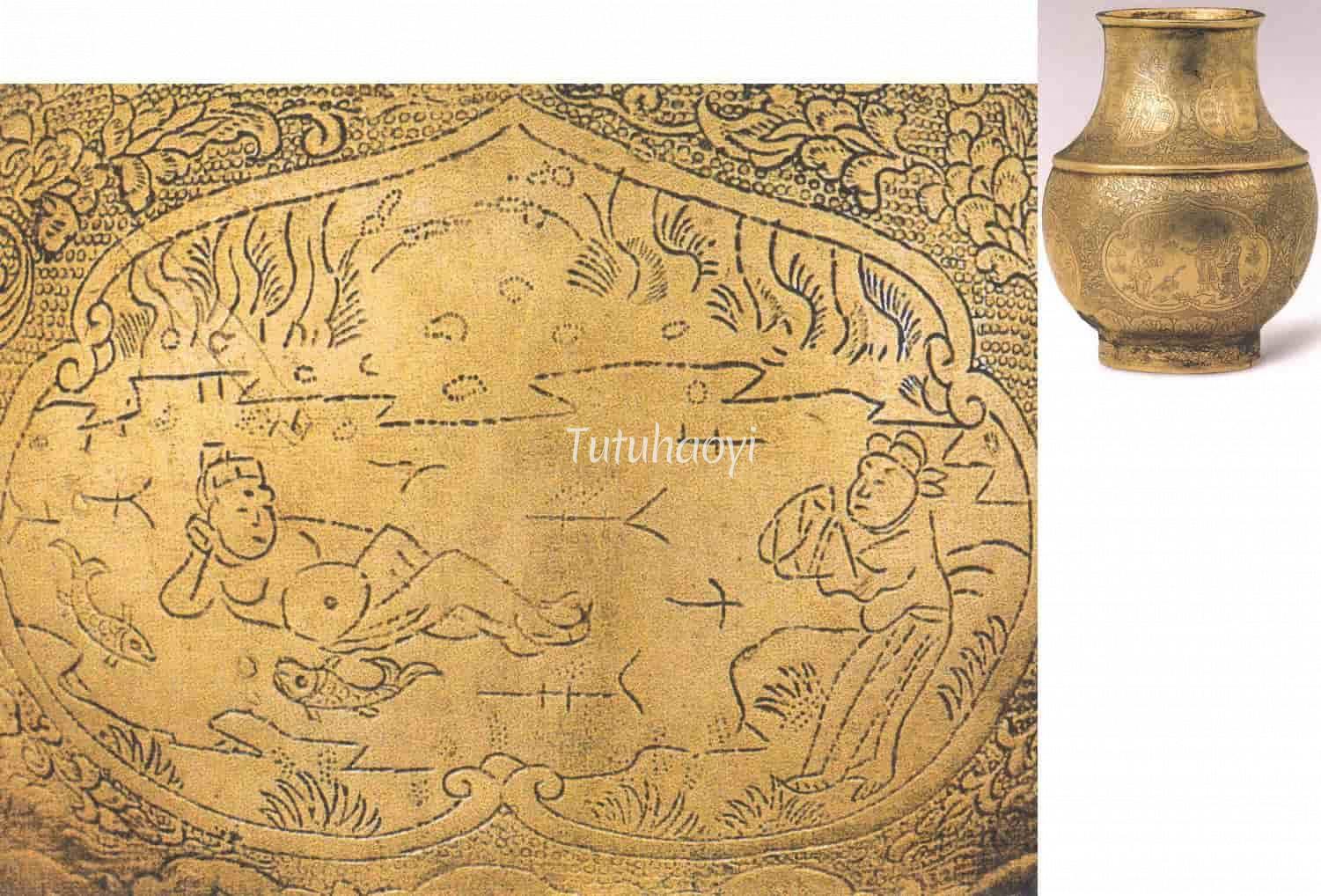

image above: tomb mural (detail), Jin dynasty (1115–1234), Shanghaolao Village, Huguan county, Shanxi province, China

Wang Xiang (王祥 185–269) served as the Grand Protector (taibao 太保) in the Western Jin court (西晋 265–316 CE) and, as a significant politician, has his biography in the Book of Jin (jinshu 晋书), an official historical text covering the dynasty’s history. When he was a boy, his mother passed away. His stepmother was not kind to him, often speaking ill of him before his father. One bitterly cold wintry day, his stepmother had a craving for the carp (li 鲤). Wang Xiang went to the frozen lake, took his clothes off, and lay on the icy surface trying to melt the ice in order to catch some fish. Suddenly, the ice cracked and out jumped two carp, which Wang Xiang could take back to please his parents. It was Wang’s devout filial piety that moved the dragon king residing in the lake, who sent him the carp as a reward.

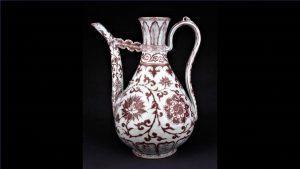

The earliest example to tell Wang Xiang’s filial piety story is found on a copper jar excavated from a Liao / Khitan dynasty (916–1125) burial. In one of the four cartouches, a naked Wang Xiang with a noticeable pot belly is lying on his right side with his palm under his head resting on the right elbow. A well-dressed man on the right is bowing to Wang to show his respect.

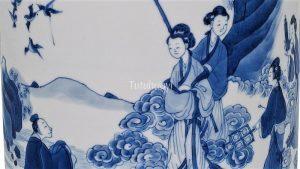

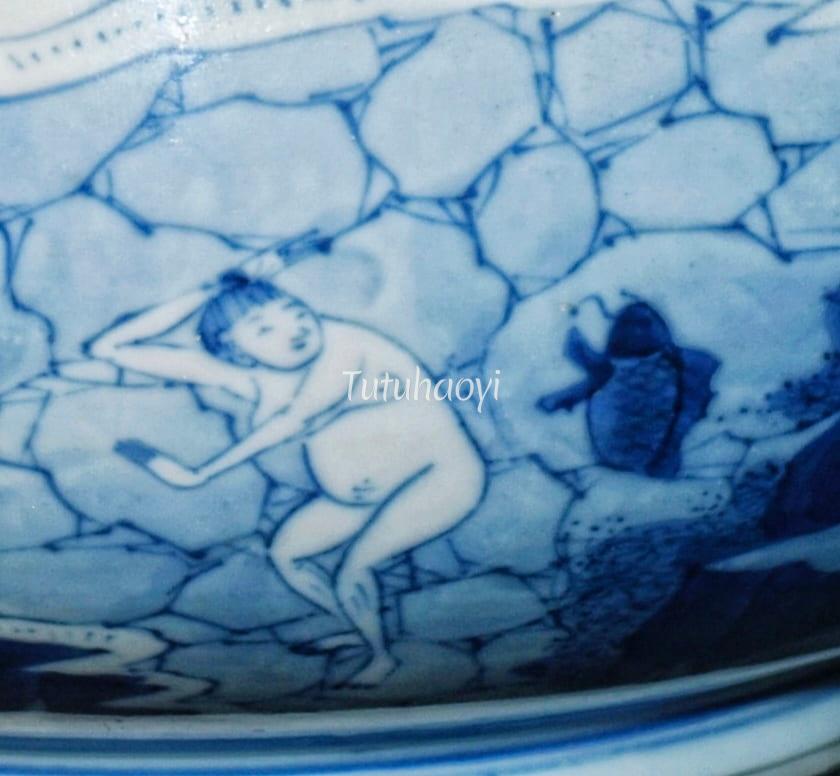

The tradition of depicting Wang Xiang naked is obviously inherited by the Kangxi porcelain painter towards the end of the 17th century, as is shown in the scene depicted on a blue-and-white censer dated 1695, and so, it seems, is the man’s bulging belly.

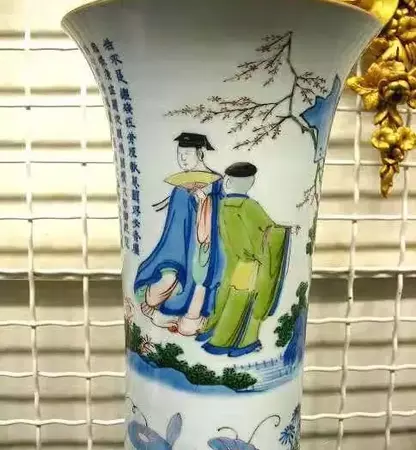

In contrast, the elaborate line drawing of the scene on a 16th-century ceramic pillow adopts a conservative approach and portrayed Wang Xiang fully-clothed, even wearing a pair of thick-soled shoes, for reasons such as modesty and propriety. He seems to be floating over the grid water surface with his right hand supporting his head, as if he were sun-bathing in the Dead Sea. The artist has added a fairy with an elaborate tall hairdo and dangling hairpins to offer our hero a large fish with long whiskers.

The porcelain painter of the famille rose dish of the 18th century apparently follows the fully-clothed tradition and has arranged Wang Xiang to be standing by the lake. Obviously, the painter has no knowledge of foreshortening and has to represent the depth of the lake surface in a vertical way, which is parallel to the standing Wang Xiang. As a result, contemporary viewers such as Christie’s experts have to interpret the crackled frozen lake as a ‘stone wall’, which is ‘issuing a fish’. On the other hand, not knowing the story behind the cobalt-painted scene, the verdict that Sotheby’s experts give about the Wang Xiang story on the blue-and-white censer is ‘a naked figure dancing about in an icy pool, accompanied by a carp’. They interpret Wang’s lying position on ice with his head resting on his right wrist and his left arm across his torso as ‘dancing’.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.