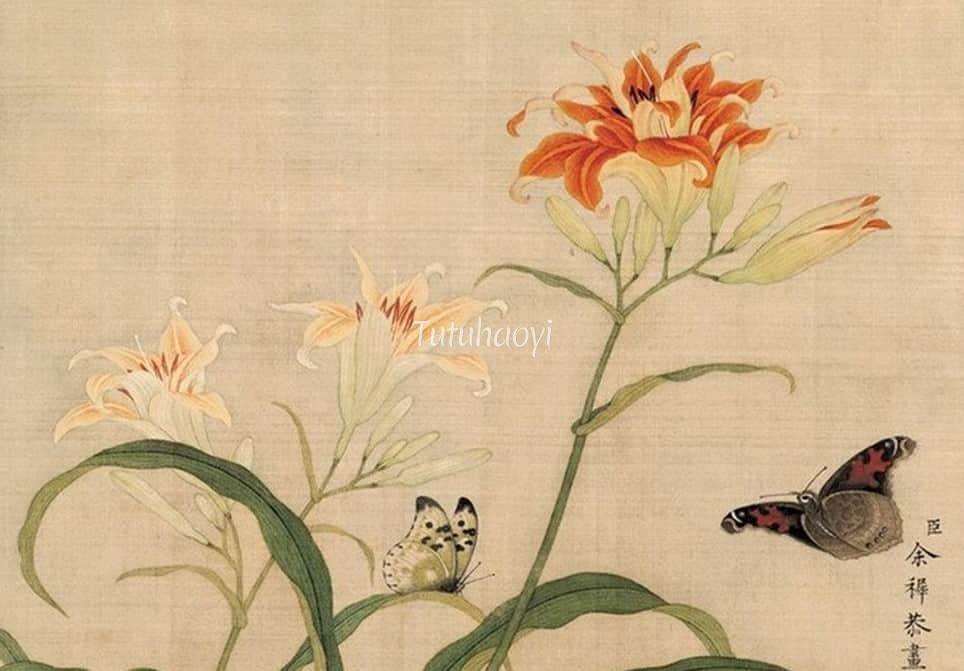

Editor: Lily flowers are frequently present in biblical painting and when in the context of Christianity, they traditionally symbolise Mary’s purity and virginity. However, in traditional Chinese culture, daylily symbolises motherhood and when combined with butterflies, they pun on a message which wishes longevity for mothers. Here is Dr Yibin Ni’s unique research on the differences of symbolic meanings of lily between Western and Chinese cultures 《萱草百合中西辨》.

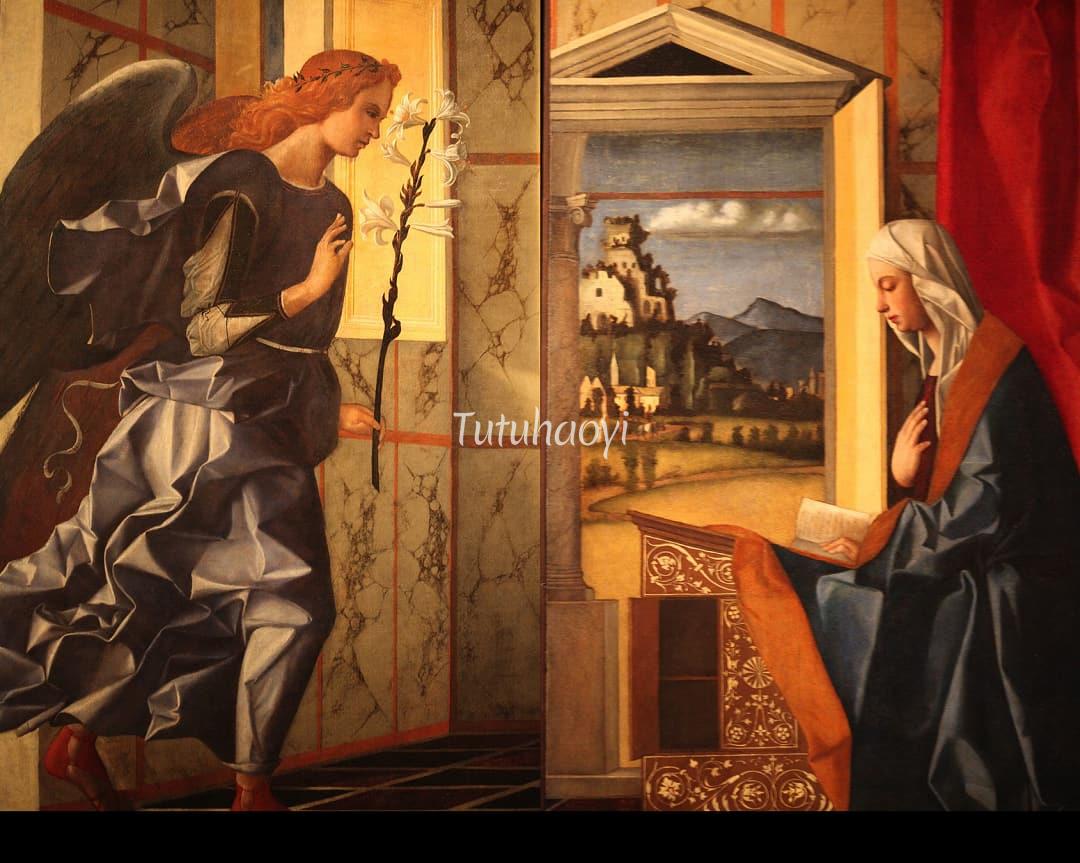

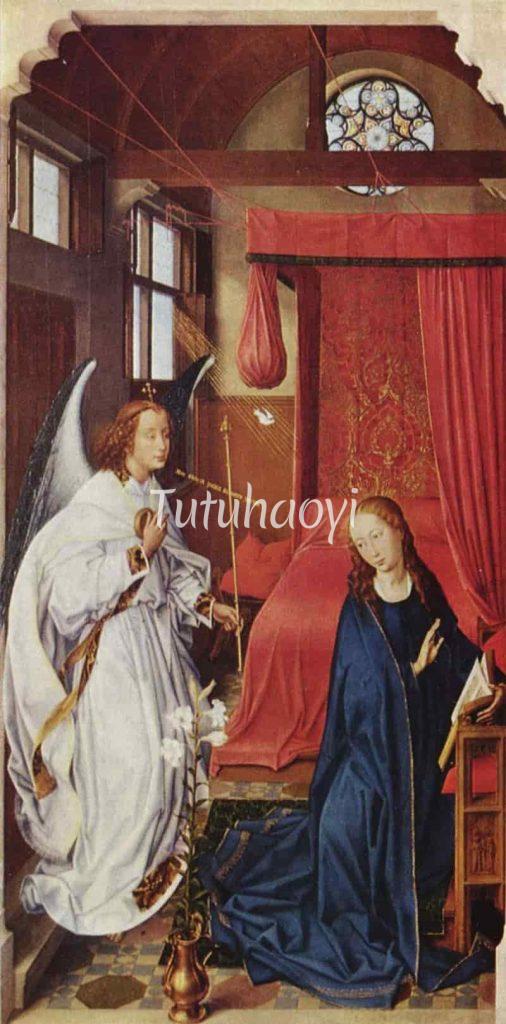

Lily flowers are frequently present in versions of the biblical painting ‘Annunciation’. The archangel Gabriel would hold lily stalks in his hand and told the Virgin Mary that she had ‘found favour with God’ or a bunch of lilies may sit prominently in a vase or pot in the vicinity. However, to the uninitiated, Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Annunciation’ may seem to be a depiction of a male suitor handing out flowers to his beloved.

In the context of Christianity, these white flowers of the species lilium candidum are known as ‘Madonna lily’ and traditionally symbolise Mary’s purity and virginity. It is said that lily had had no scent till Mary’s touch made it emit an exquisite aroma. Botanical symbolism usually originates from ancient literature, in which plants are often used as metaphors for abstract concepts such as purity or humility. As early as the 7th century, the Ven. Bede (673-735) compared the Virgin Mary to a white lily, the white petals to her pure virginal body and the golden anthers to the radiance of her soul. A few centuries later, Saint Bernard (1090-1153) described Mary as ‘the violet of humility, the lily of chastity, the rose of charity.’

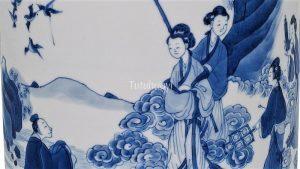

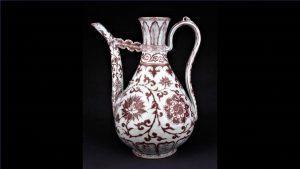

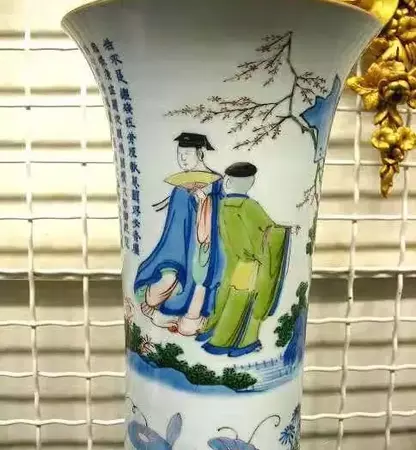

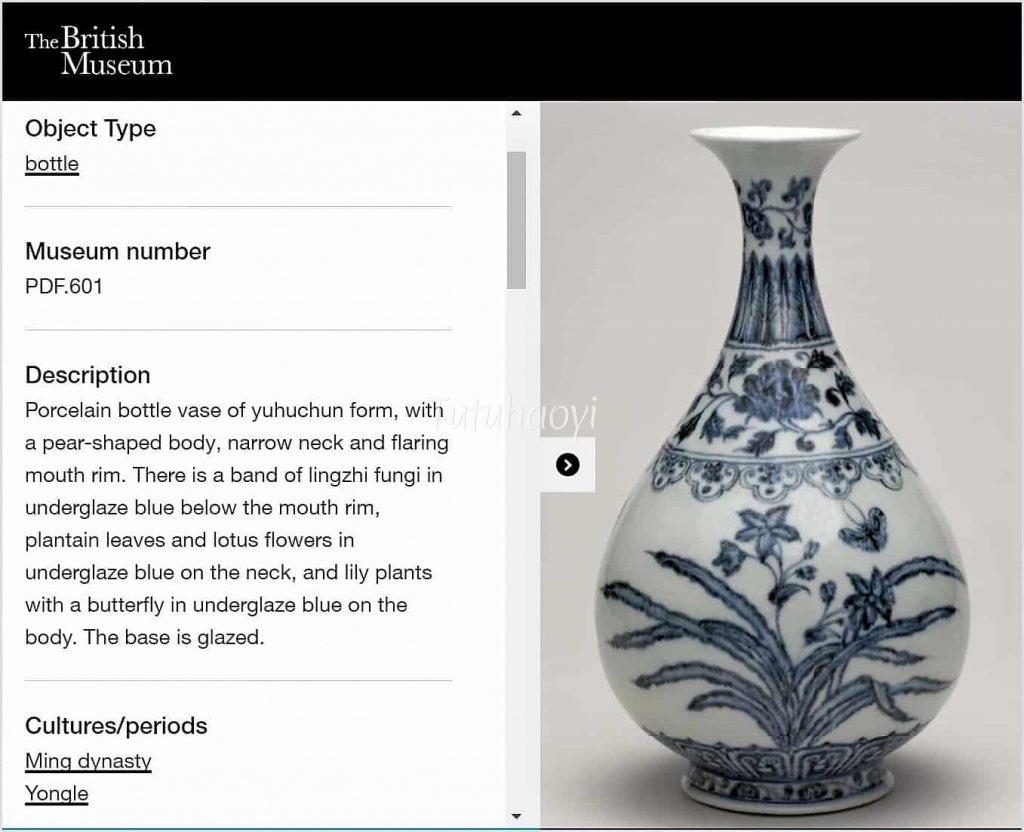

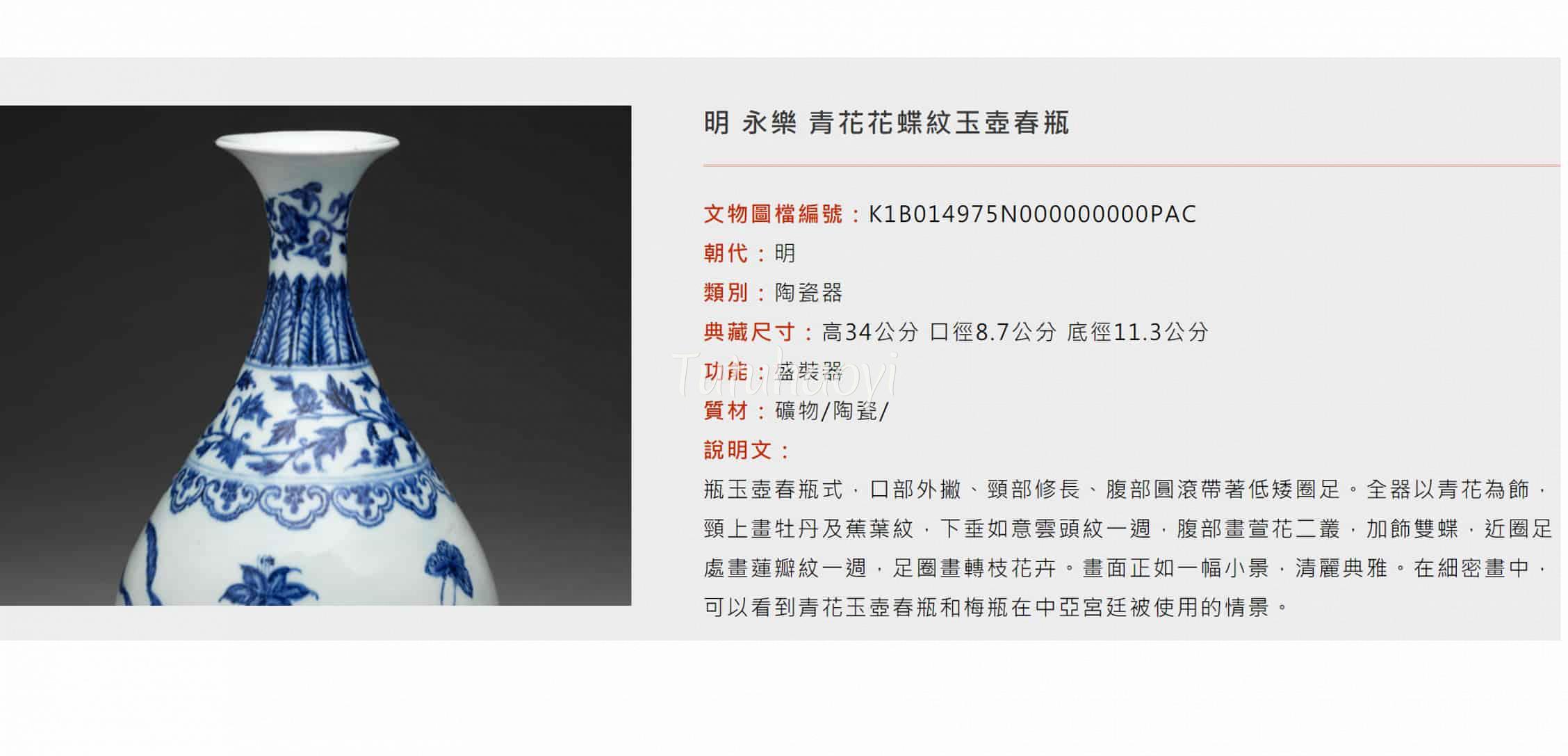

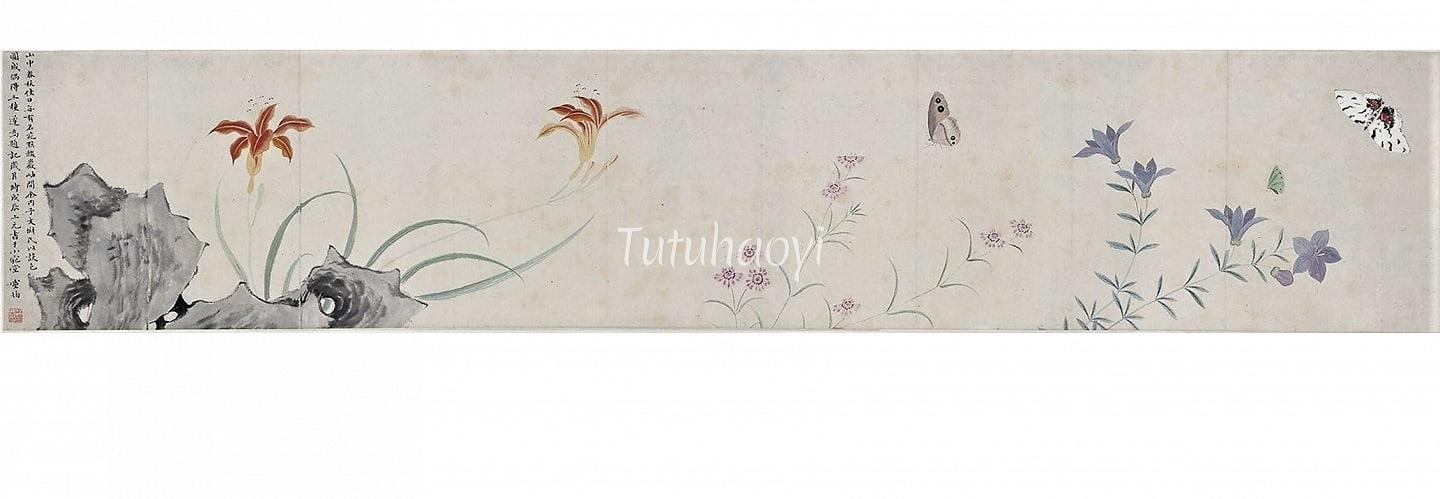

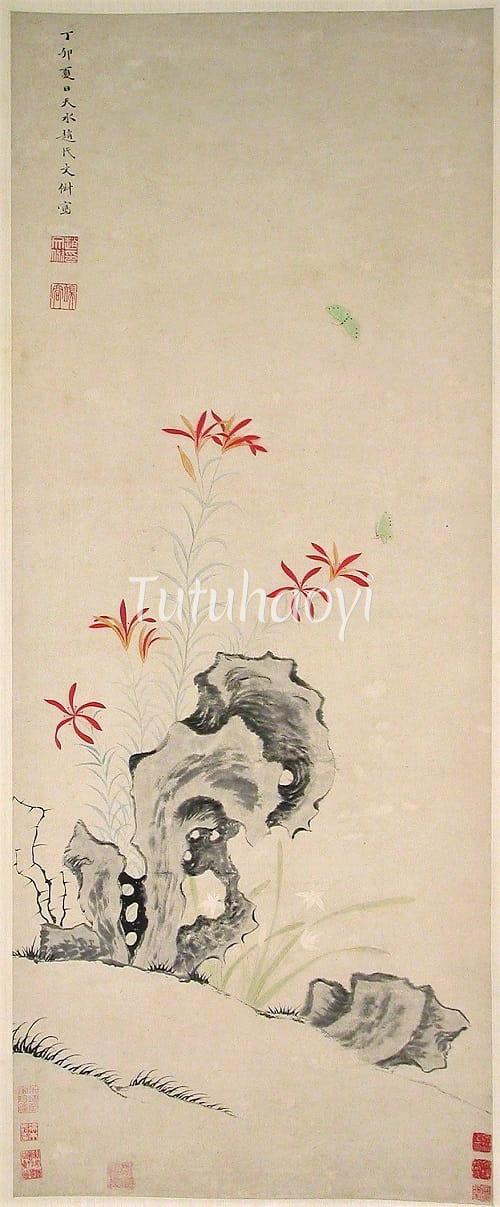

Such culture-specific knowledge applies to images on Chinese art works, too. The British Museum has a Ming Yuhuchun vase in their collection, which is embellished with a culturally significant pun rebus design. The online catalogue uses the description of ‘lily plants with a butterfly in underglaze blue on the body’, which can be regarded as the first level of art-historical understanding, concerning only the primary or natural subject matter in Erwin Panofsky’s (1892-1968) iconological framework. So can the Chinese description of a similar vase in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, which says ‘painted on the belly are two bunches of daylily plus a couple of butterflies.

As a matter of fact, the seemingly botanical design on the porcelain vase professes loud the loving message of ‘May mother live up to a ripe old age’ to a viewer well-versed in traditional Chinese culture, as is vindicated by versions of the same theme found on different media cited here.

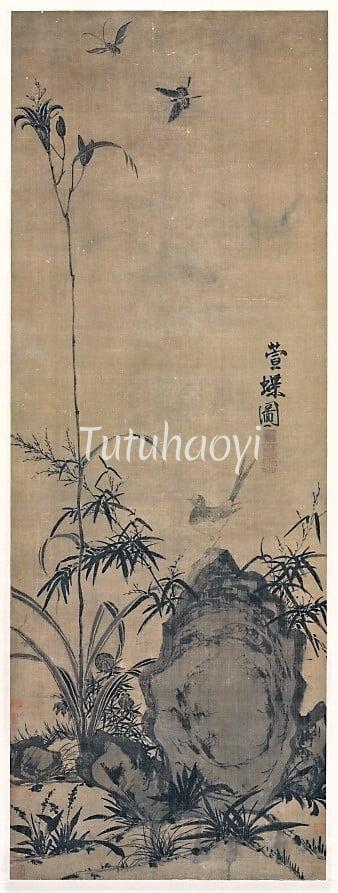

One of them has a clear inscription ‘萱蝶图 xuandie tu’ written on it. The Chinese character ‘萱 xuan’ in the picture title comes from ‘xuancao 萱草’, the Chinese name for the Asian ‘daylily’. A couplet from the poem Bo Xi 伯兮, in the section of Odes of Wei (Weifeng 卫风) of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing 诗经) is considered to make the earliest association of daylily with the ‘North Hall’, which is traditionally the quarters of the lady of the house and which has acquired its name because of its orientation. In the Mao Tradition of the Classic of Poetry (毛诗传 Mao shi zhuan), attributed to Mao Heng (毛亨), who lived during the 2nd or 3rd centuries BCE, the couplet ‘焉得谖草,言树之背’ is explained as meaning that daylily will help people forget sadness and the lady of the house often plant the flower outside her quarters. Ever since, daylily has come to symbolise motherhood in addition to its well-known depression-relieving function and become a favourite subject for poets and artists alike, especially for women artists. The character ‘蝶 dié’ in the painting title is the Chinese word for ‘butterfly’, which puns on ‘dié 耋’, the Chinese word for ‘octogenarian’. Thus, the combination of daylily and butterflies are used as an apt theme of a heartfelt birthday wish for mothers.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.