Editor: The following article is a discussion of the substitution of a mythical beast for a horse as Grand Duke Jiang’s mount on three classic porcelain vases adorned with the same story scene of ‘Bo Yi and Shu Qi Trying to Stop the Mighty Zhou Army’. The author, art historian Dr Yibin Ni, focuses on the origin and evolution of the two disparate but homophonic expressions ‘Sibuxiang’ in late imperial China and clarifies the terminological confusion in the contemporary world, as is reflected in the relevant entry in the Wikipedia.

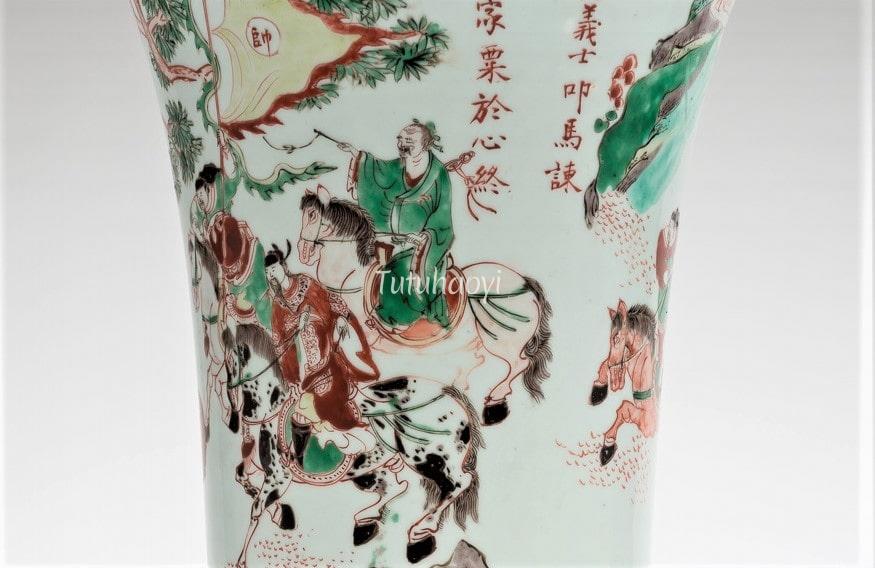

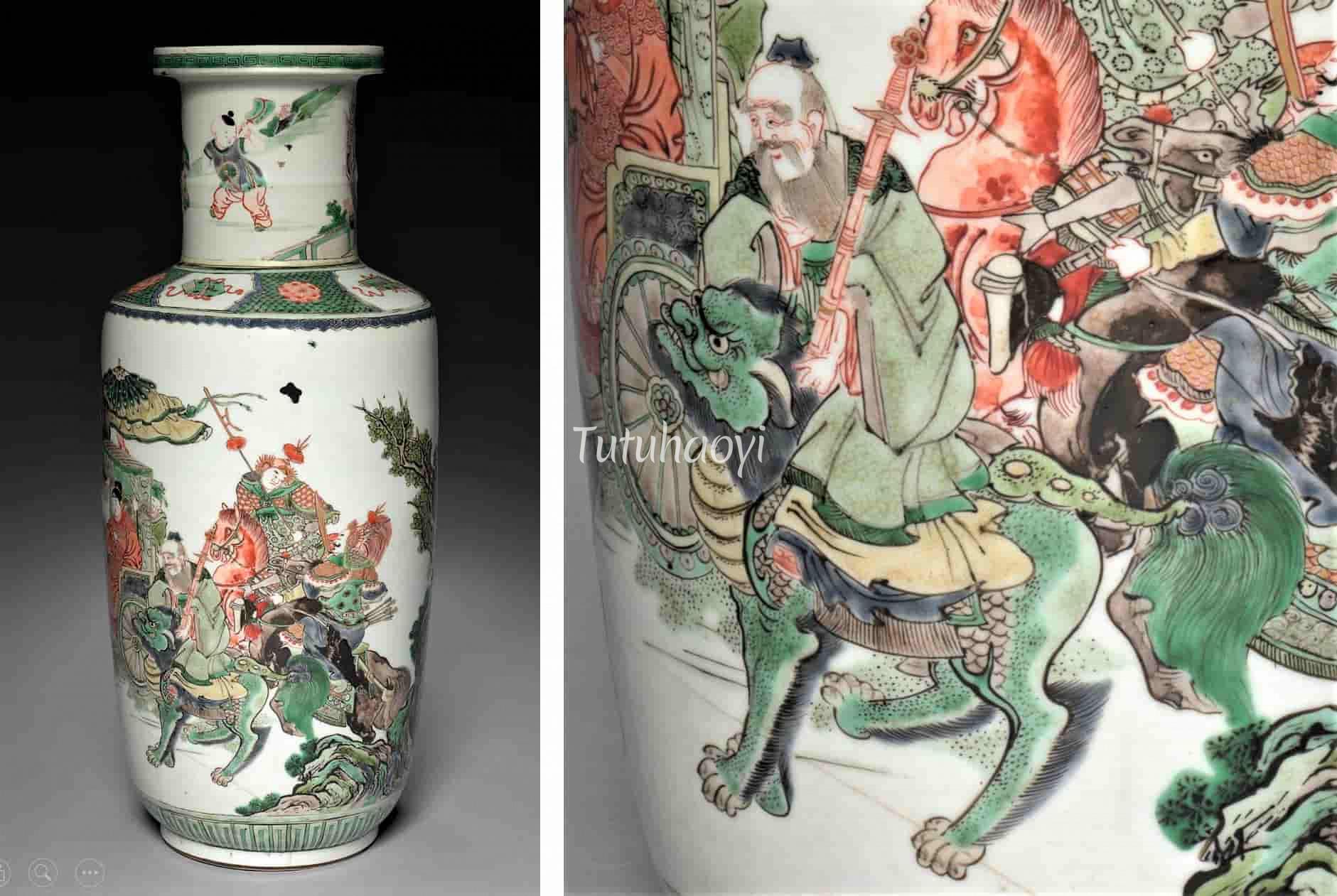

featured image above: porcelain vase (detail), Shunzhi period (1644-61), courtesy of the Butler Collection

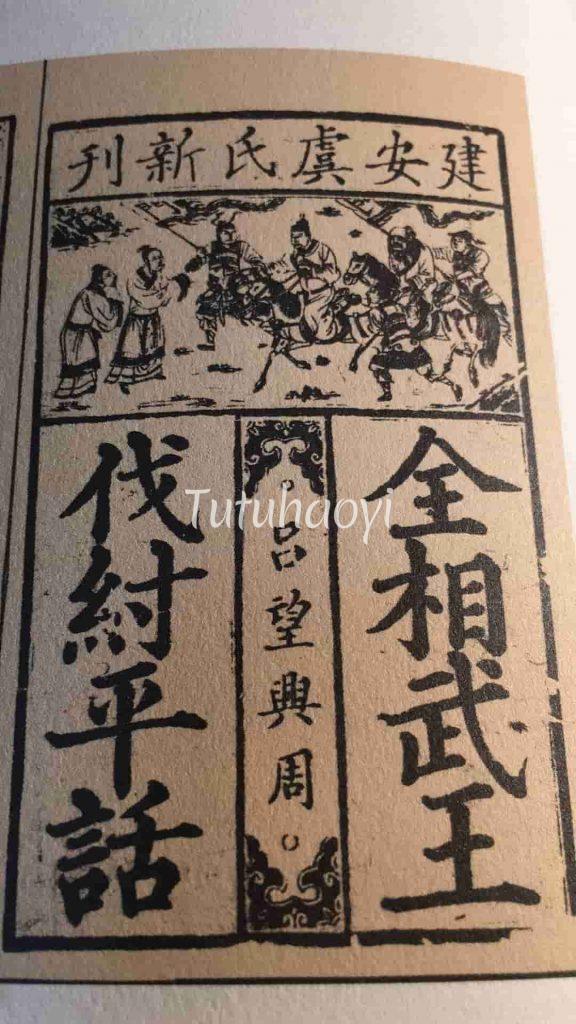

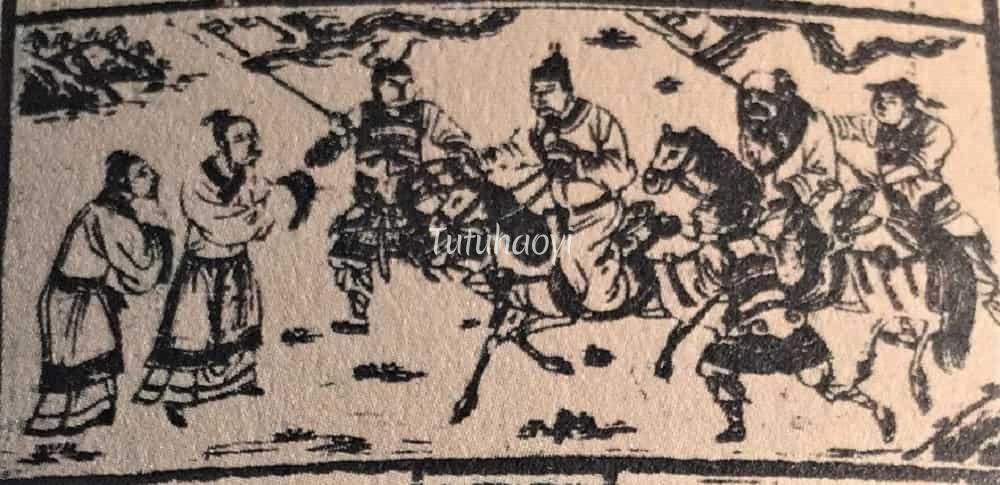

On the Shunzhi-period five-coloured enamel vase, the Grand Duke Jiang Ziya (姜子牙, also called Jiang Tai Gong 姜太公) rides an ordinary horse, which clearly has a one-toed hoof. This obviously follows the pictorial tradition of woodblock printed illustrations of a popular historical novel Story of King Wu launching a campaign on King Zhou of Shang (全相武王伐纣评话, Quanxiang Wuwang Fazhou Pinghua) published in the 14th-century, as is illustrated below.

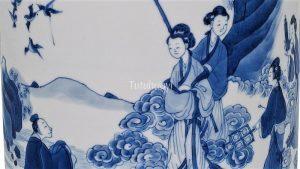

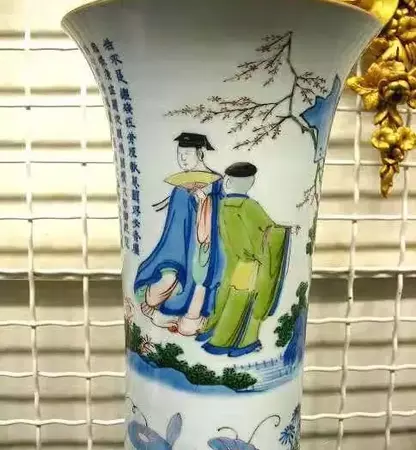

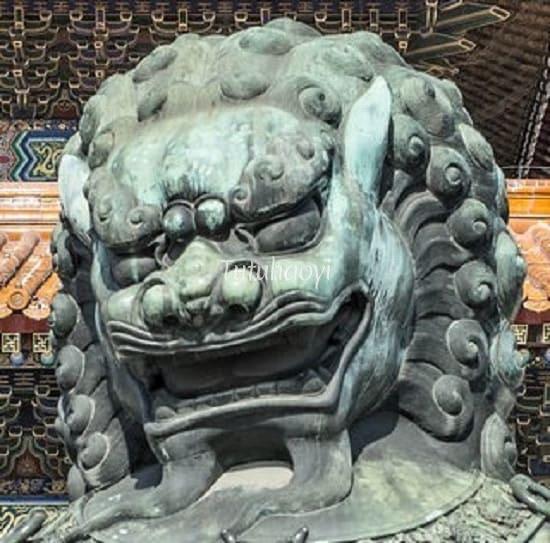

However, the Grand Duke Jiang’s mount on the Jie Rui Tang rouleau vase is a beast that has two-toed hooves and an exaggerated hairy tuft at the end of its tail. The head of this mythical beast resembles those of the Chinese guardian lions, two of whose Ming examples are shown here for comparison.

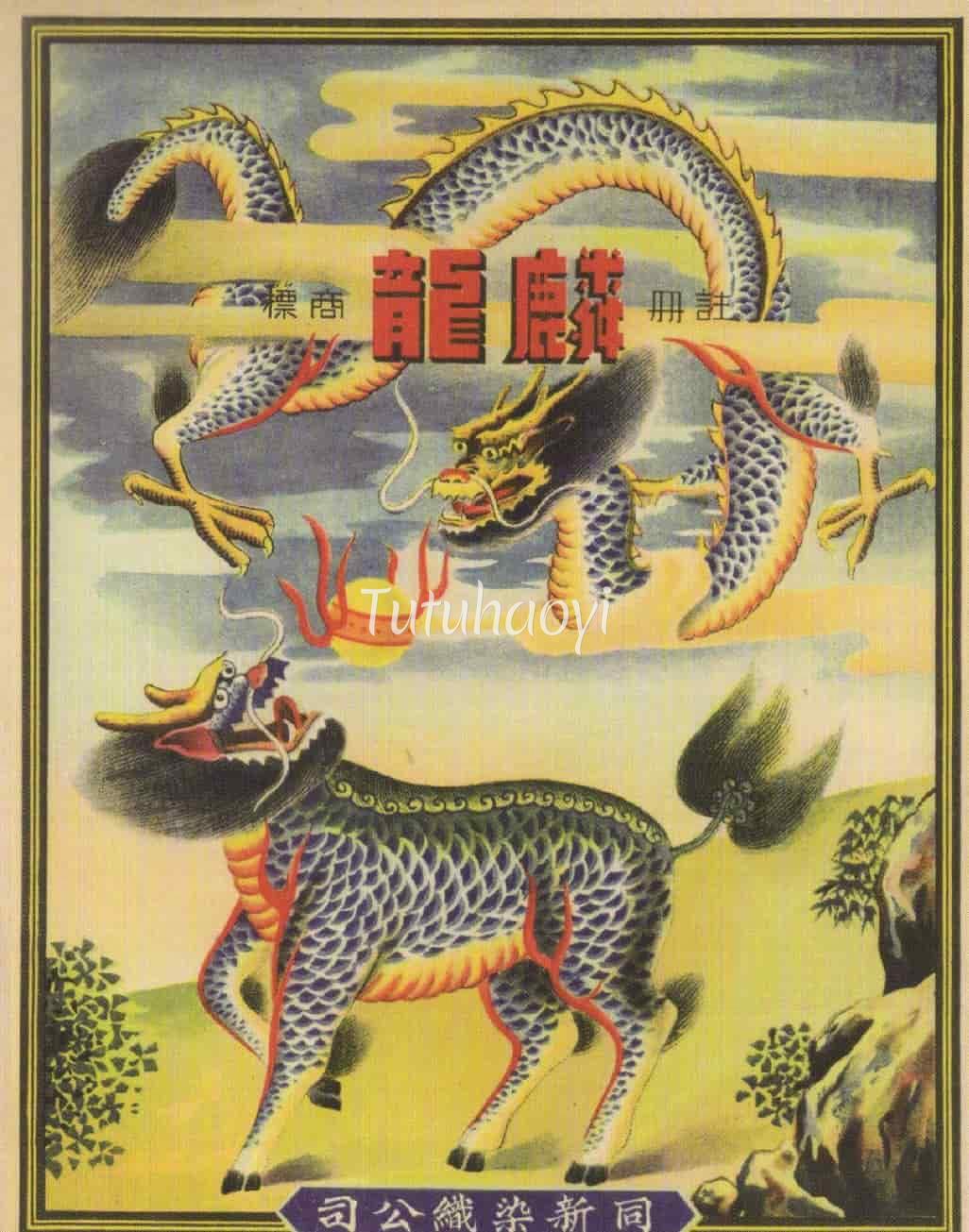

It is evident that the image of Jiang’s mount was influenced by its description in the late-Ming novel The Investiture of the Gods (封神演义, Fengshen Yanyi), published about three quarters of a century earlier. In Chapter 38 of the novel, Jiang’s mentor, a Zeus-like Primeval Lord of Heaven (元始天尊, Yuanshi Tianzun), offered him his own mount to defend himself against all sorts of demonic beasts he may confront with in his imminent battles. The fantastic beast of this creator of Heaven and Earth must be unusual enough and exceptionally outstanding, so it was nick-named ‘四不相 (Sibuxiang)’, i.e. ‘neither-fish-nor-fowl’, literally meaning ‘four unlikes’. The nickname was supposed to indicate that it was an assembly of the essence from some most powerful and benevolent mythical creatures including ‘a qilin (麒麟)’s head, a unicorn-xiezhi (獬豸)’s tail, and a long (龙)-dragon’s body’ (麟头豸尾体如龙), to name three of them.

One may wonder how come the Jiang’s mount on the two famille verte vases has a lion’s head instead of a qilin’s, which is dictated in the novel. This may be explained by the fact that Jiang’s counterpart in the enemy army, the almighty Wen Zhong (闻仲), rides his signature steed, a black qilin and, therefore, it is reasonable for Jiang’s mount to have a head distinctively different from that of Wen Zhong’s mount.

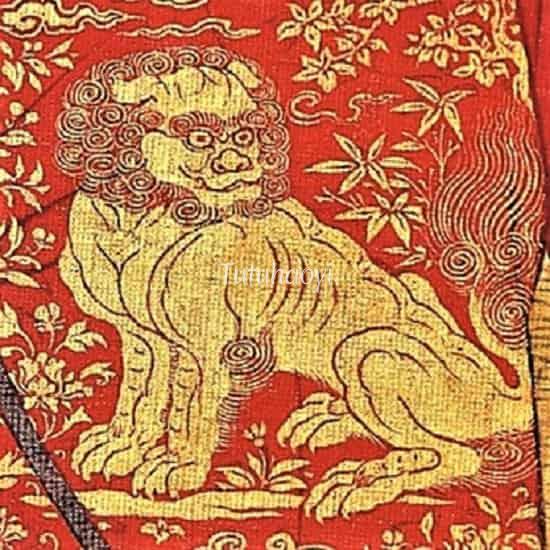

Also, how does a unicorn xiezhi look like? Well, from the images passed down by our ancestors, qilin and xiezhi are often indistinguishable. Comparing Jiang’s mount on the two famille verte rouleau vases above with the fairly standard images of qilin and xiezhi illustrated here, it is apparent that the tufted tail and the folded throat and chest are noticeable common denominators. It is interesting to note that the typical qilin has two-toed hooves, as has Jiang’s mount on the Jie Rui Tang vase, while the xiezhi illustrated in the largest imperial encyclopaedia has paws, typically with five digits, as has Jiang’s mount on the Cleveland vase. This interchange of the feet reflects the fuzzy image of these mythical beasts in folk minds.

Apart from the fact that Grand Duke Jiang’s mount has a qilin’s head but is not a qilin, has a xiezhi’s tail but is not a xiezhi, has a long-dragon’s body but is not a dragon, etc. and, therefore, was named ‘Sibuxiang, the “Four Unlikes”’ in Chinese by the novelist, there is a more profound reason for this nickname.

In the section of the Hereditary House of the Grand Duke of Qi, in The Records of the Grand Historian (史记 Shi Ji), a seminal work of ancient Chinese history, there is an account of how the strategist Jiang Ziya was recruited by the Count of the West of Zhou (周西伯), King Wu’s late father. Before the Count of the West of Zhou was about to go on a hunting trip, he had a divination session performed. The oracle turned out to be the following, ‘What to be captured will not be a dragon with horns or without horns, nor a tiger, nor a brown bear. What you are to catch is a great assistant to a hegemon (西伯将出猎,卜之曰:所获非龙非彲,非虎非羆,所获霸王之辅).’ Because this oracle actually contained four ‘nots’ or four negatives, the novelist cleverly coined the word ‘Sibuxiang, the “Four Unlikes”’ to allude to this historical anecdote when he named Jiang’s signature mount.

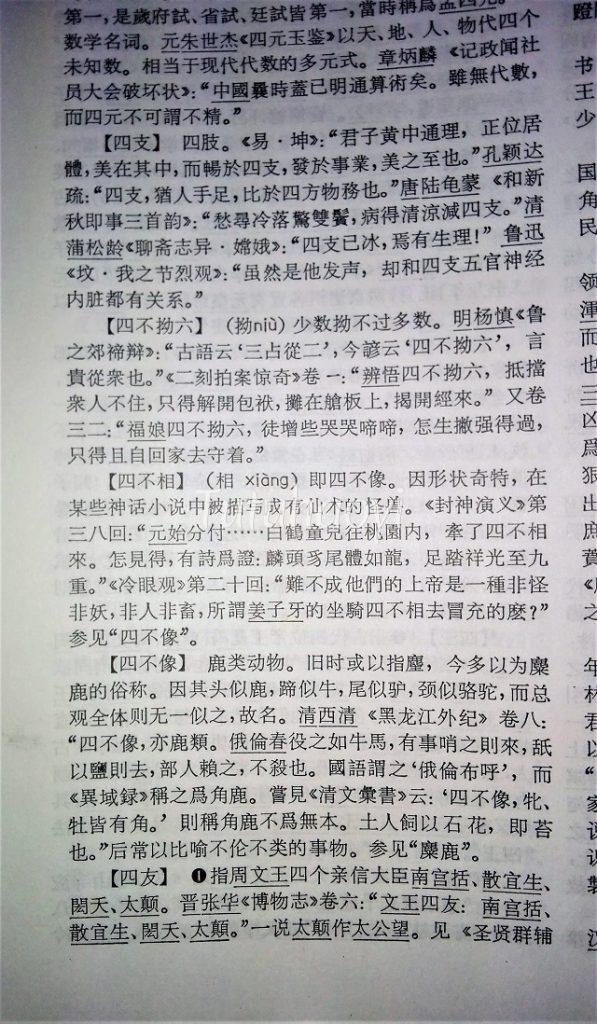

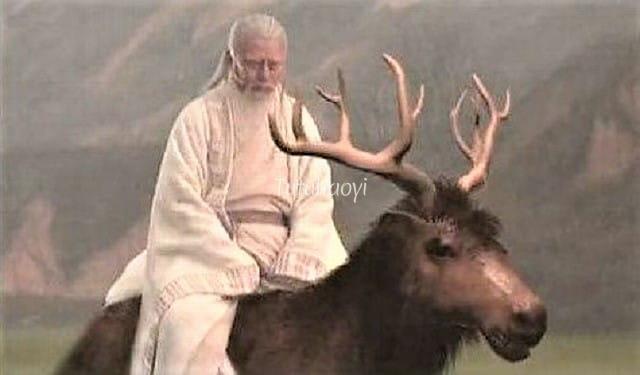

There is a misconception in contemporary popular culture that Jiang’s mythical mount is a Père David’s deer for the simple reason that this animal’s informal name is also ‘sibuxiang (四不像)’. The English Wikipedia entry ‘Père David’s deer’ claims, ‘By this name, this undomesticated animal entered Chinese mythology as the mount of Jiang Ziya in Fengshen Bang (translated as Investiture of the Gods), a Chinese classical work of fiction written during the Ming Dynasty.’ (cited on June 1, 2021)

As a matter of fact, historically and linguistically, there is no evidence to show that the nickname of Jiang’s mount and that of the Père David’s deer, though coincidentally identical, have had any connections until now. According to The Comprehensive Dictionary of Chinese Words and Phrases (汉语大词典), the so-called ‘most inclusive available Chinese dictionary’, the earliest citation of ‘sibuxiang’ meaning the Père David’s deer is from the book Information about Heilongjiang (黑龙江外记), which was completed in 1810, two centuries later than The Investiture of the Gods’s publication date.

In the earliest reference book that explains the Père David’s deer’s nickname, Research into the Origins of Colloquialism (俗语考原), published in 1937, the animal is said to have acquired its nickname because of ‘its having the head of a deer, the feet of an ox, the tail of a donkey, and the neck and back of a camel (其头类鹿,脚类牛,尾类驴,颈背类骆驼)’, which has little to do with the description of Jiang’s mount in the Ming novel mentioned above. As nobody has explicated this entangled mess properly, we have to make do with the screen image of Jiang riding an elaphure.

References:

- 倪亦斌:《武王子牙举旗伐商 伯夷叔齐叩马阻兵》,《读者欣赏》,兰州:读者出版传媒股份有限公司,2016-07,60-65 页

- Jeffrey P. Stamen and Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni (2017), A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection 文采卓然:潔蕊堂藏康熙盛世瓷, Jieruitang Publishing, Bruges, pp. 22-25.

The findings and opinions in this research article have been written by Dr Yibin Ni.