Editor: 2022 is the year of Tiger according to Chinese lunar calendar. Dr Yibin Ni has conducted a research overview of the pictorial representation of the tiger in the background of Chinese culture and history, from the origin of its motif in relics to various artistic forms in traditional decorative arts over the past three thousand years.

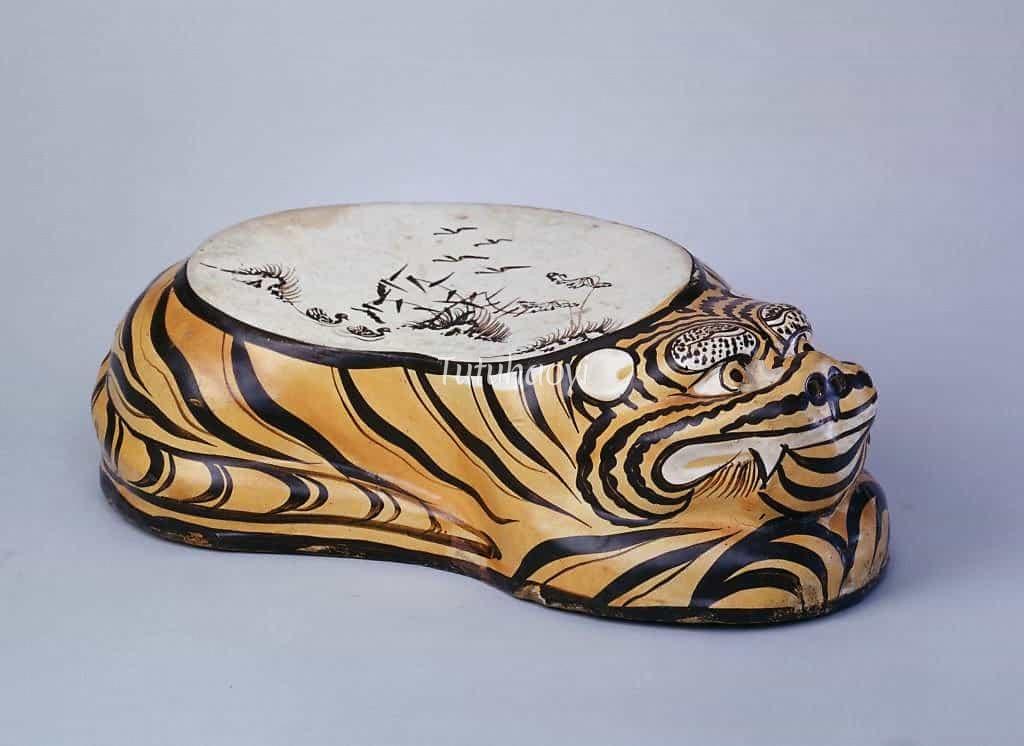

featured image above: tiger-shaped pillow, Cizhou ware, Jin dynasty (1115-1234), courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

As the largest member of the cat family, the tiger has impressed the Chinese for being ferocious, valiant, and awesome. Numerous imaginations, legends, and images have been stimulated by the fascinating impact of this majestic beast on the nation’s psyche ever since antiquity. Various versions of pictograms denoting the tiger incised on oracle bones and a marble statue of a tiger were excavated from the Ruins of Yin (Yinxu 殷墟) (dated between 1350-1046 BCE) in the historical capital of the Shang dynasty during the early part of the 20th century. They are among the earliest instances of pictorial representation of the tiger found in the landmass now known as China.

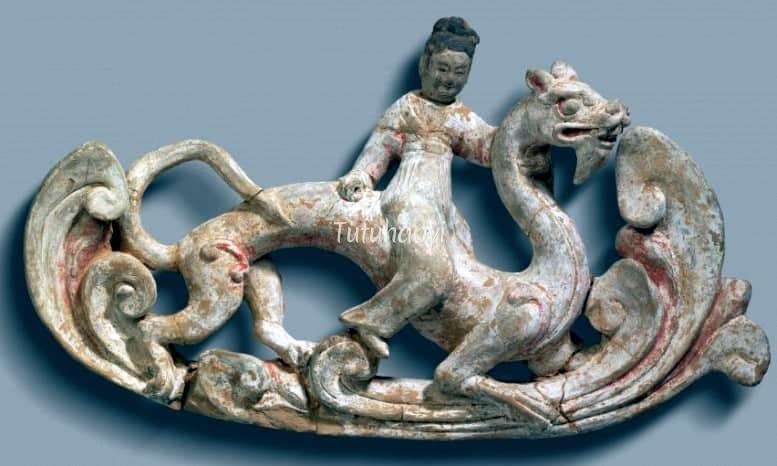

Early significant depictions of the tiger also include the shamanistic ‘monster-protector’ vessels of the Shang (商) dynasty, the naturalistic ‘tiger-devouring-bull’ scene of the Dian culture in Yunnan province, and the confrontation of an equestrian warrior with the dangerous beast on a bronze mirror. These images epitomise how people looked at the tiger in ancient society.

Shuowen jiezi (说文解字), or Explanations of Simple Graphs and Analyses of Composite Graphs, the oldest dictionary in China, finished at the beginning of the 2nd century CE, defines the tiger as the ‘lord of the beasts in the wilderness (山兽之君)’. Fengsu Tongyi (风俗通义), or Comprehensive Meaning of Customs and Mores, compiled by Ying Shao (应劭) towards the end of the 2nd century, records the contemporary custom of painting tigers on the door to ward off evil spirits in the chapter entitled ‘Sidian (祀典 i.e. Sacrificial Statutes)’. It claims, ‘The tiger is the embodiment of the yang energy and the chief of all the wild beasts (虎者,阳物,百兽之长也).’

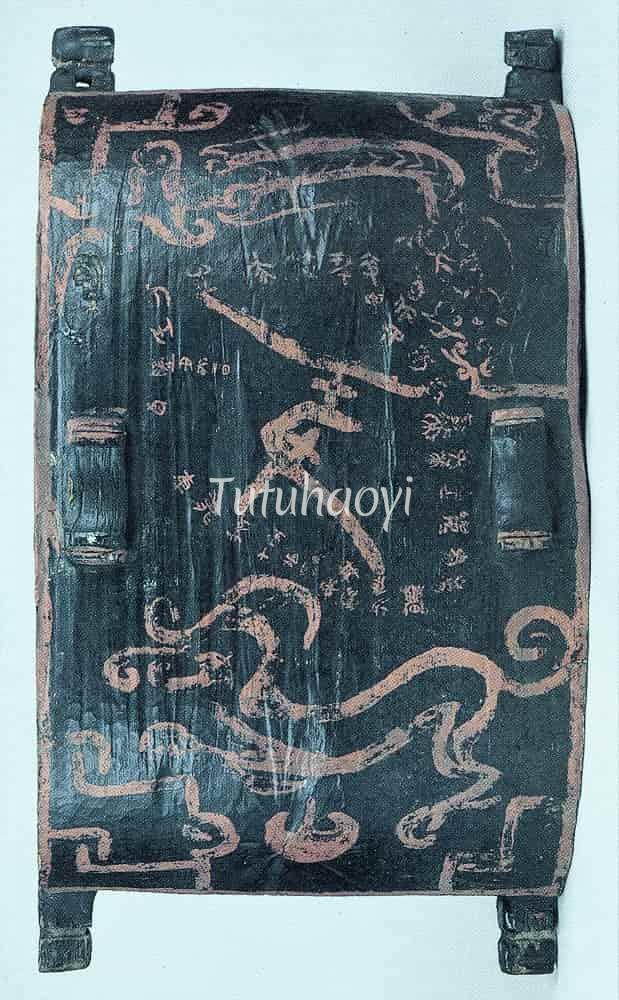

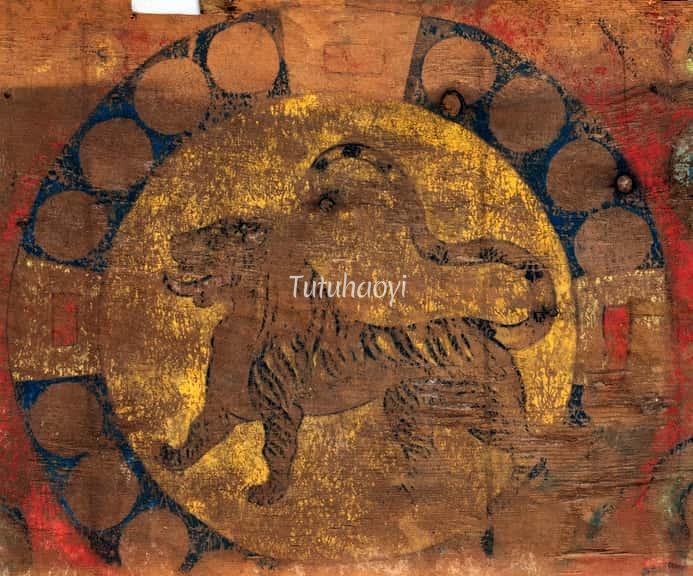

The special status of the tiger in the Chinese mind helped the animal join the rank of the ‘Four Directional Guardians’, known variously as si ling (四灵), si xiang (四象), or si shen (四神) in the literature from the Han dynasty downwards. They respectively symbolise the four cardinal directions: the Azure Dragon of the East (苍龙 or 青龙), the Scarlet Bird of the South (朱雀 or 朱鸟), the White Tiger of the West (白虎), and the ‘Black Warrior (intertwined tortoise and snake)’ of the North (玄武). The earliest image of the White Tiger as an astrological and/or astronomical entity appeared on the cover of a painted lacquer chest for clothing, excavated from the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (曾侯乙墓) in Hunan province, dated sometime after 433 BCE. The White Tiger, together with the Azure Dragon, painted in red on a black ground, features prominently among the 28 lunar mansions (二十八宿), i.e. divisions of stars in the sky, decorated on different sides of the chest.

One of the earliest textual mentionings of the White Tiger as the guardian of the West, is found in The Huainanzi (淮南子), or The Discourses of the Huainan Masters. The book is a collection of discussions held in the court of Prince of Huainan (179-122 BCE) before 139 BCE. In the chapter entitled ‘The Treatise on Heaven (天文训 tianwen xun)’, there is the saying: ‘The West is related to metal (of the Five Elements / Phases), …… and its related beast is the White Tiger (西方, 金也, ……其兽白虎). In a 12th-century Song-dynasty commentary of the Chun guan (春官 i.e. Offices of Spring) chapter of the Zhou li (周礼 i.e. Rituals of Zhou) by Zheng E (郑锷), the tiger is said to be ‘the beast symbolising the direction of the West and the virtue of righteousness (虎, 西方义兽)’. The Rituals of Zhou is one of the classics of Confucianism composed probably during the third century BCE. Metal (金 jin), wood (木 mu), water (水 shui), fire (火 huo), and earth (土 tu) were conceived in ancient China in a system of wuxing (五行) as cosmic agents responsible for all the changes in the world. They are seemingly comparable to the classical elements of the ancient Mediterranean world. However, the Wuxing System may be better described as ‘Five Phases’. The Five Constant Virtues (五常 wu chang) advocated by Confucianism respectively correspond to the Five Phases.

Eave-end tiles with the Four Directional Guardians representing four cardinal directions including the White Tiger first came into being during the Han dynasty (汉朝 206 BCE – 220 CE) and the Xin dynasty (新朝), or the ‘New dynasty’ (9-23 CE). The Xin dynasty, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang (王莽 c. 45 BCE – 23 CE), existed between the Western and Eastern Han dynasties and was short-lived. The tradition of decorating architecture with the Four Directional Guardians continued for centuries to come.

Utensils in zoomorphic shapes such as that of a tiger are inspired by ancient shamanistic beliefs of animals’ mysterious power. Chamber pots called ‘hu zi (虎子)’ or the ‘tiger’ were popular during late Han and Six Dynasties periods. Cizhou kilns produced tiger-shaped pillows during the Jin 金 and Yuan 元 periods.

Tigers are often depicted, often alone, in an imposing majestic pose with their tail sticking high up in a landscape.

In the Chinese zodiac, there is a twelve-year cycle of specific animals with the tiger as Number Three, which matches the third of the twelve Earthly Branch symbol 寅 yin.

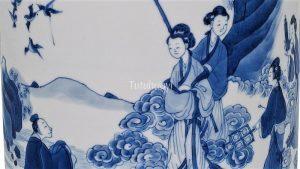

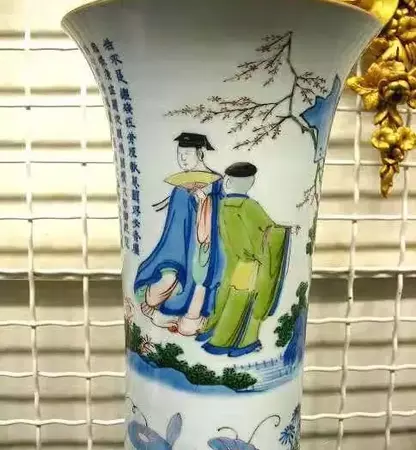

Traditional decorative scenes featuring the tiger include Celestial Master Zhang (张天师) with His Personal Mount Tiger, the ‘Five Supernatural Beasts (五灵 wu ling)’, the ‘Four Directional Guardians (四灵 si ling or 四神 si shen or 四象 si xiang)’, the ‘Four Mythical Creatures (四灵 si ling)’, Li Kui (李逵) Fighting a Tiger, Monk Chou Separating Two Fighting Tigers, Tiger-Taming Lohan (伏虎罗汉), Twelve Zodiac Signs (十二生肖属相), Wu Song (武松) Slaying a Tiger, Yang Xiang (杨香) Subduing a Tiger to Rescue Her Father, etc.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.