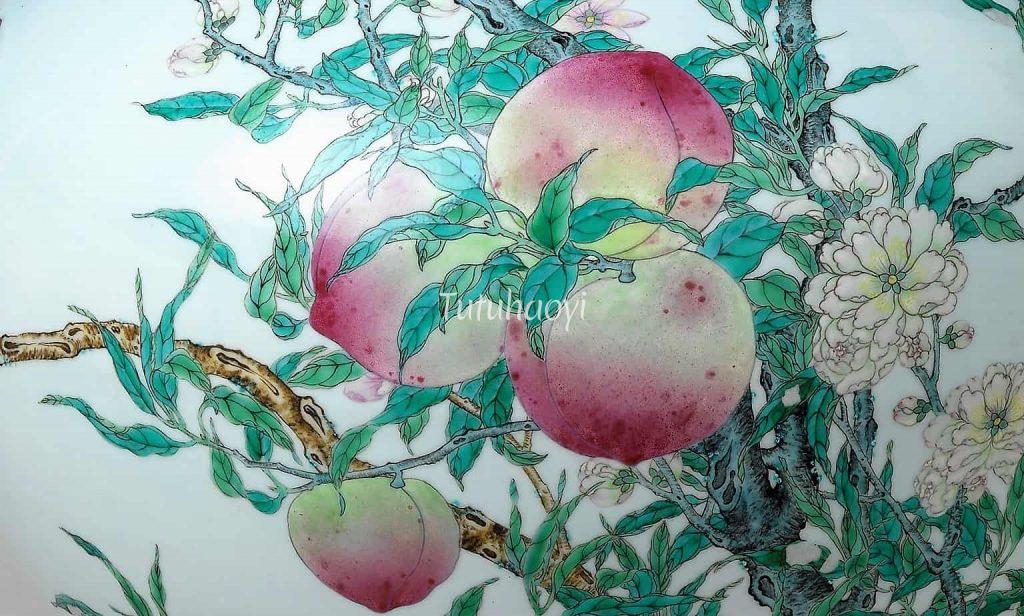

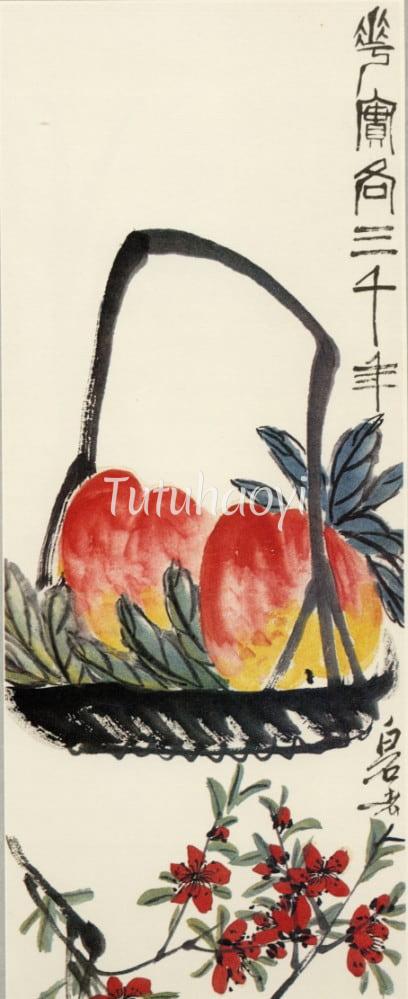

Editor: In Chinese culture and pictorial art, the peach fruit is often used to wish for long life on birthday parties. How does this fruit become associated with the idea of longevity? Here is Dr Yibin Ni explaining to us the origin of legendary stories related to the peach through his research work over literatures and treasurable artworks.

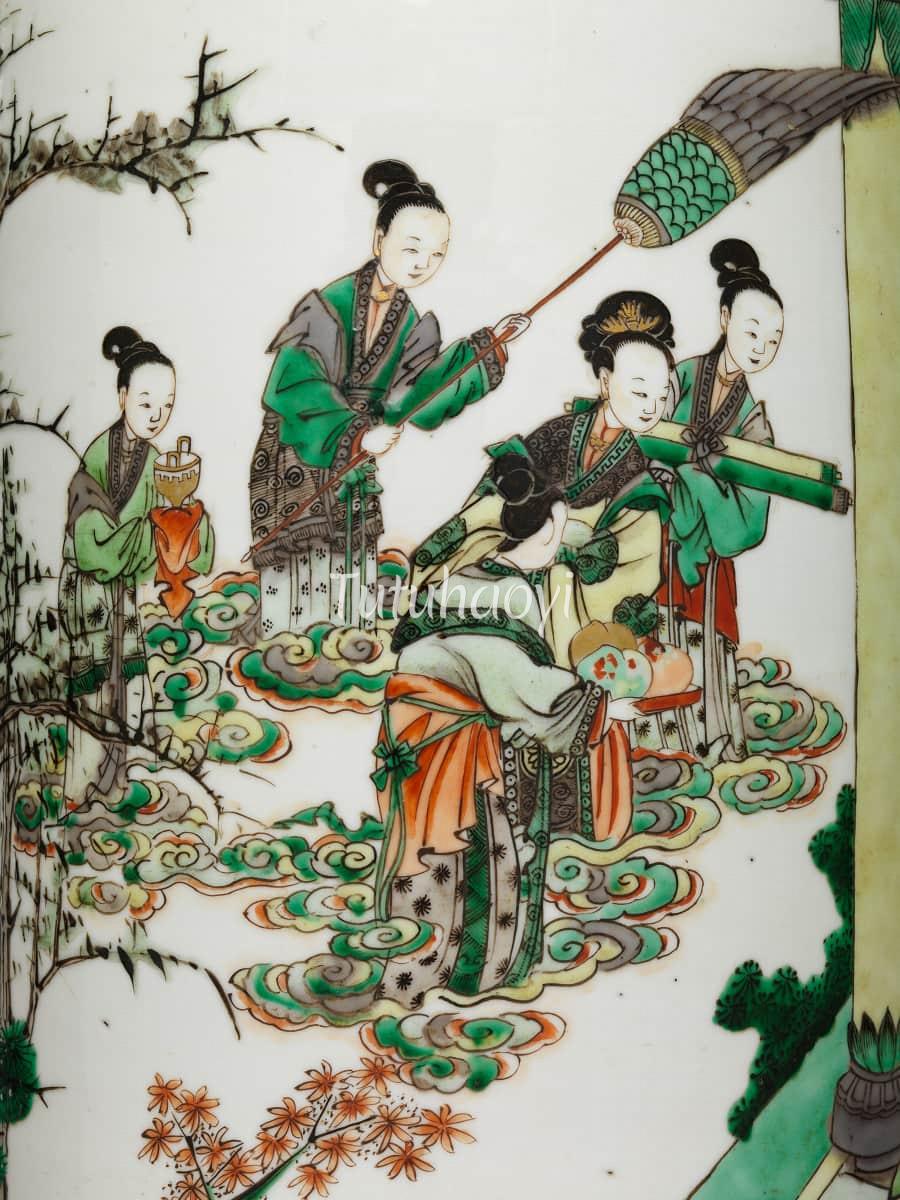

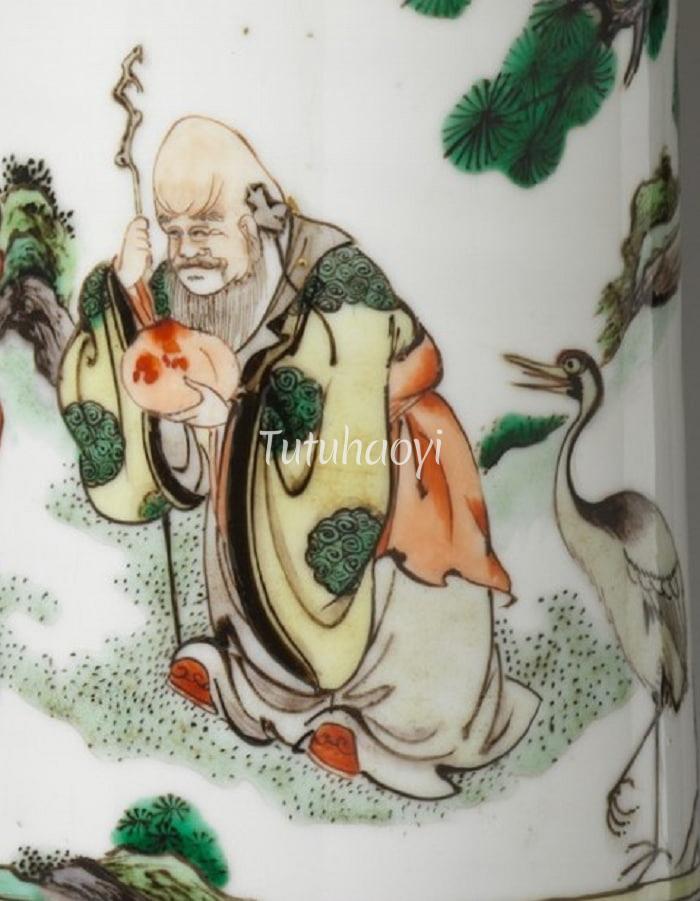

image above: porcelain vase with nine peaches (detail), Qianlong period (1736-95), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

In Chinese pictorial art, the voluptuous rosy fruit of the peach is most likely to be associated with the idea of longevity or immortality – the obsession to pursue a very long life. However, apart from being juicy and sweet, peaches do not have any intrinsic property that will prolong one’s life. The supposed magic value of peaches in China came from legends dating back to the third century.

Records of Miscellaneous Matters (《博物志》), compiled by Zhang Hua (张华) (232-300), a scholar living during the Western Jin period (西晋) (265-316), and The Stories of the Emperor Wu of Han 《汉武帝内传》, a pamphlet appearing during the Eastern Jin period (东晋) (317-420), give an account of a legendary meeting between the Emperor Wu of Han (汉武帝) (156-87 BCE) and the Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu 西王母). During the meeting, the immortal Queen Mother produced seven peaches, five presented to the emperor and the Queen Mother ate two herself. She wondered why when she saw him keeping the peach stones in front of his seat. He told her that the peaches were so delicious that he wanted to have them cultivated in the palace. The Queen Mother said that the peach would take three thousand years to fruit and his land may not be good enough for it to grow. It is the millennia that these peaches take to grow and fruit that give them the mystic property of conferring immortality to people who eat them.

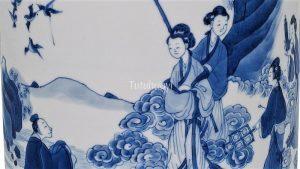

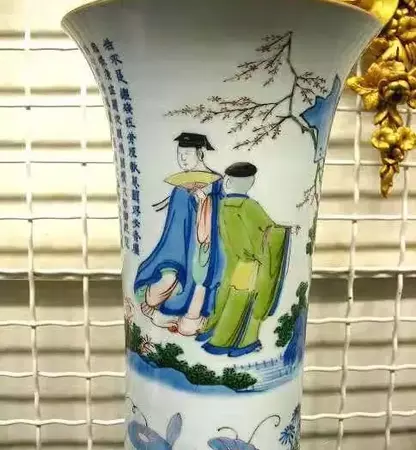

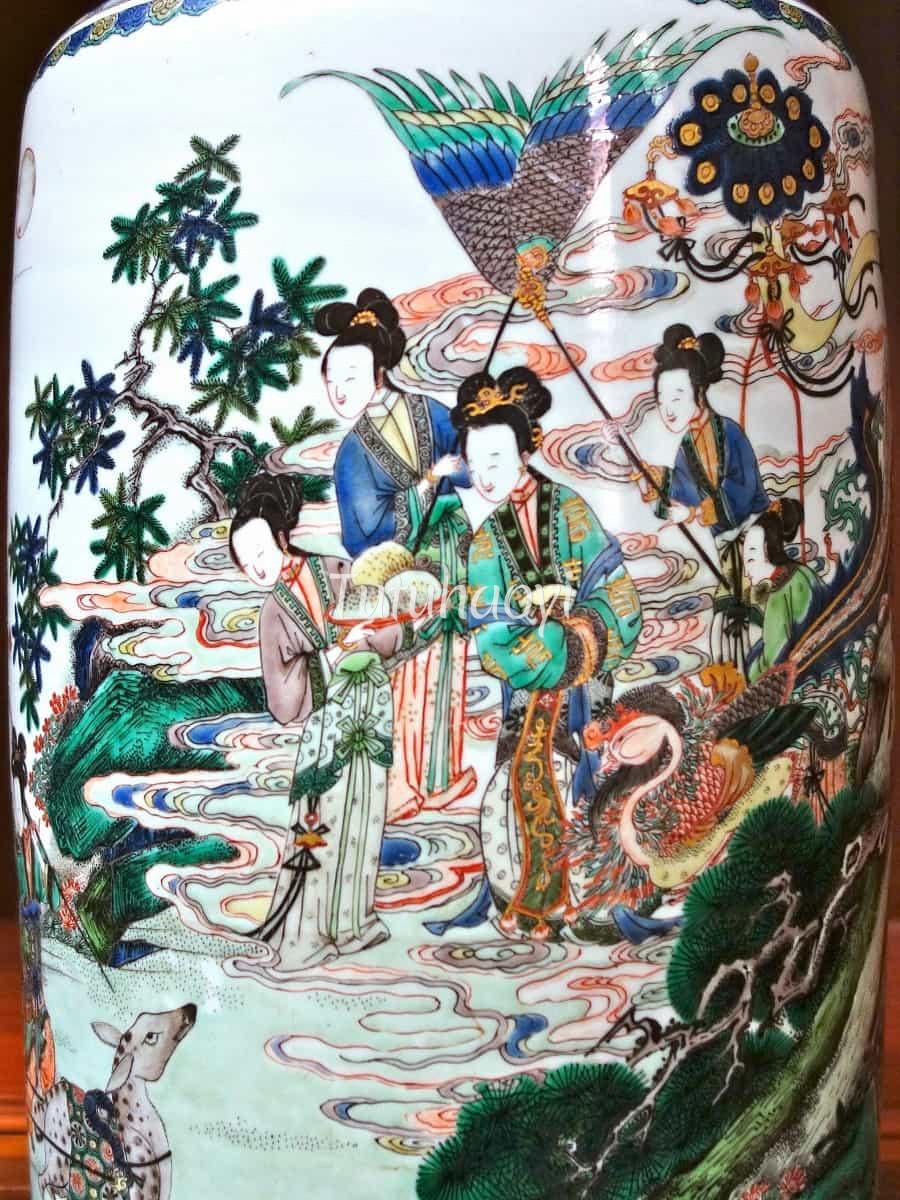

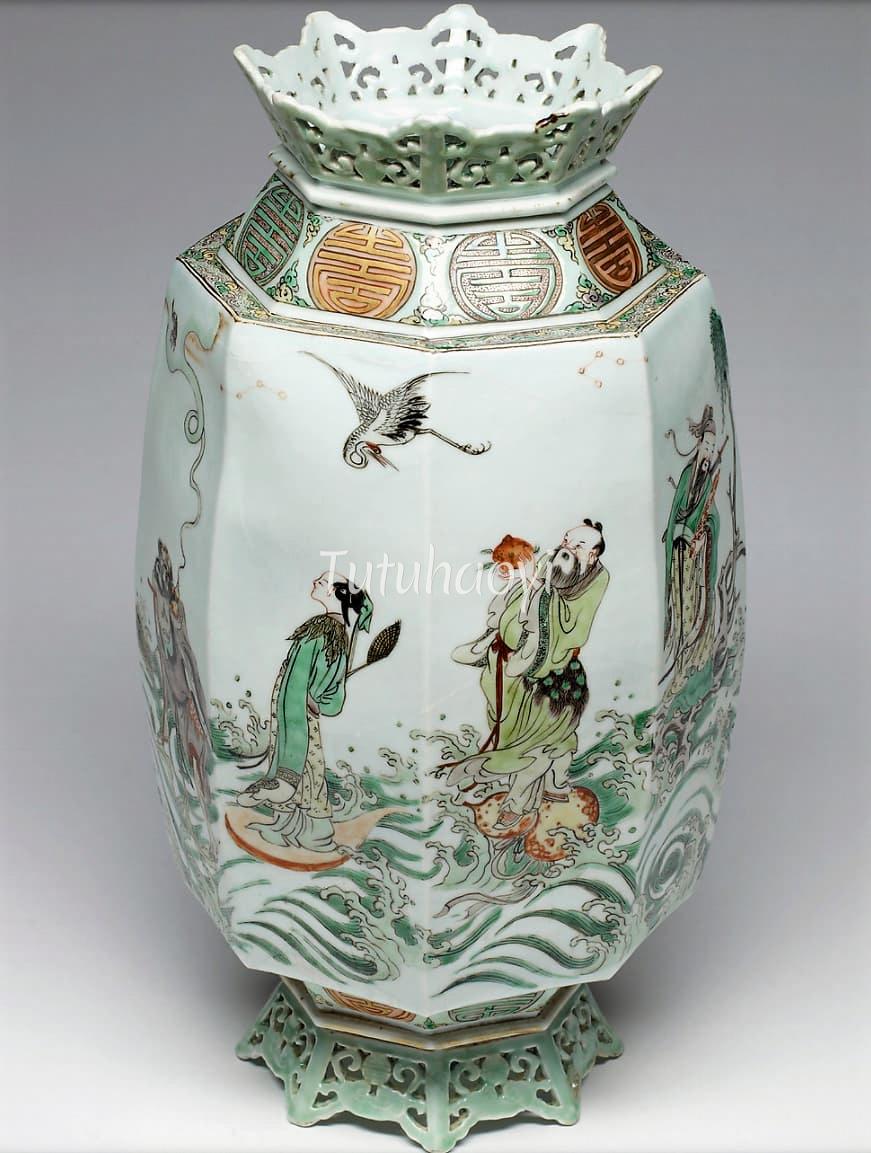

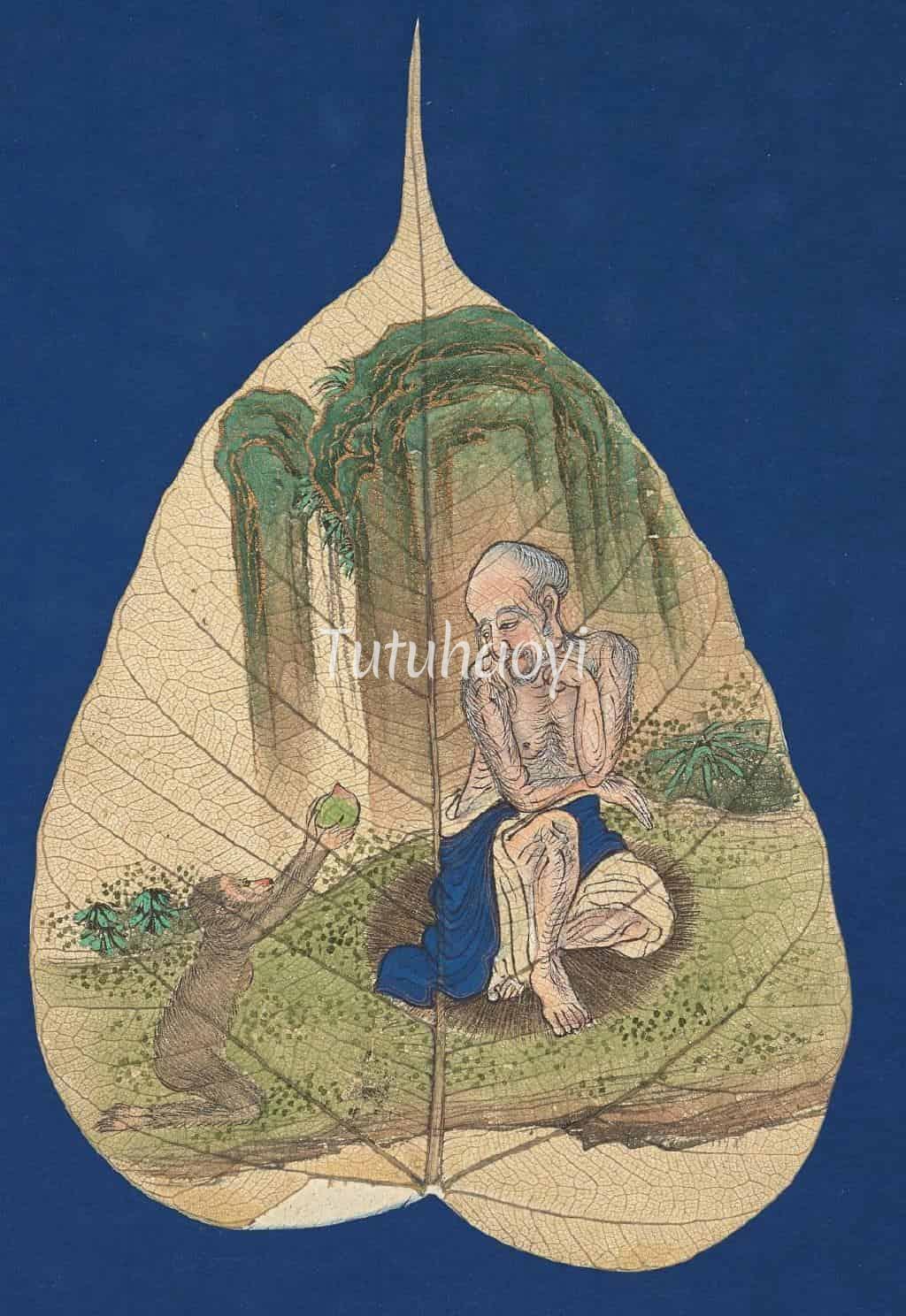

The story gradually grew more elaborated. The Queen Mother was said to hold ‘Feast of Peaches’ to entertain deities, immortals, and fairies on her birthday which fell on the third day of the third lunar month. The famous Eight Daoist Immortals (八仙) would travel across high sea to attend this fashionable party. Later on, the Monkey King (孙悟空) was put in charge of the Peach Garden in Heaven. When he heard that he was not on the guest list of the ‘Feast of Peaches’, he flew into a rage and ate most of these precious peaches in his custody. The party was ruined and the Monkey King became the target of the whole angry pantheon. All of these anecdotes further involved the Eight Daoist Immortals and the monkey with the immortality peach myth.

As a symbol of longevity, the peach fruit is often paired with the other potent symbols with similar meaning, such as the crane, the lingzhi (灵芝 fungus), and the shou 寿 character for ‘longevity’, and is also associated with legendary immortals such as the monkey or the Monkey King (Sun Wukong 孙悟空), the Old Man of the South Pole (南极仙翁), also known as the Star God of Longevity (寿星), and Dongfang Shuo (东方朔), whose prominent deeds include stealing divine peaches from the Queen Mother’s peach garden.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.