If you mistake a motif in a traditional Chinese picture, you could have misinterpreted the meaning of the whole image intended by the ancient craftsman. Dr Yibin Ni has used the following example to illustrate the hidden meaning of a series of images in the context of Chinese pun rebus culture.

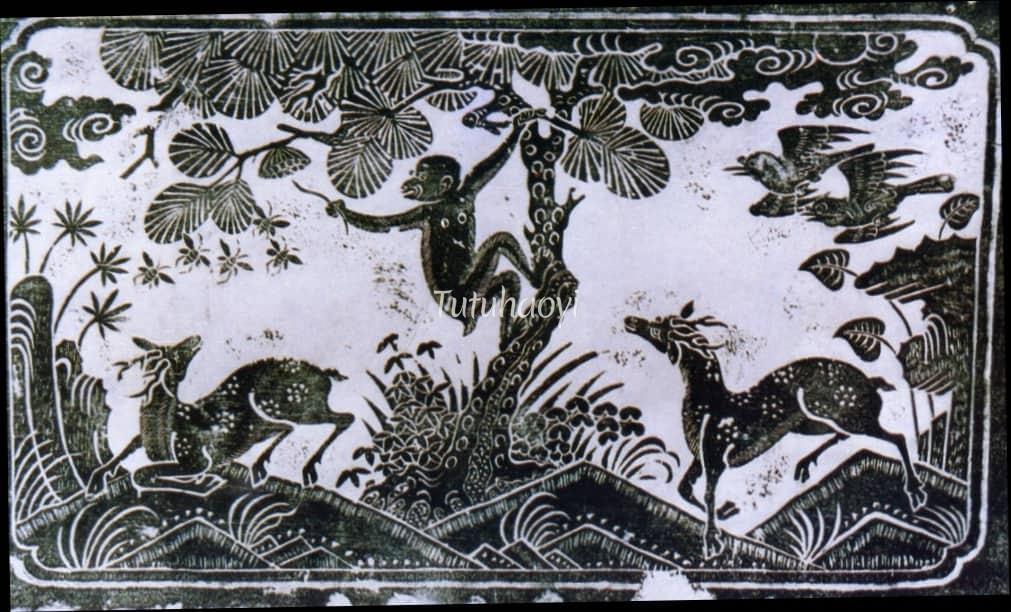

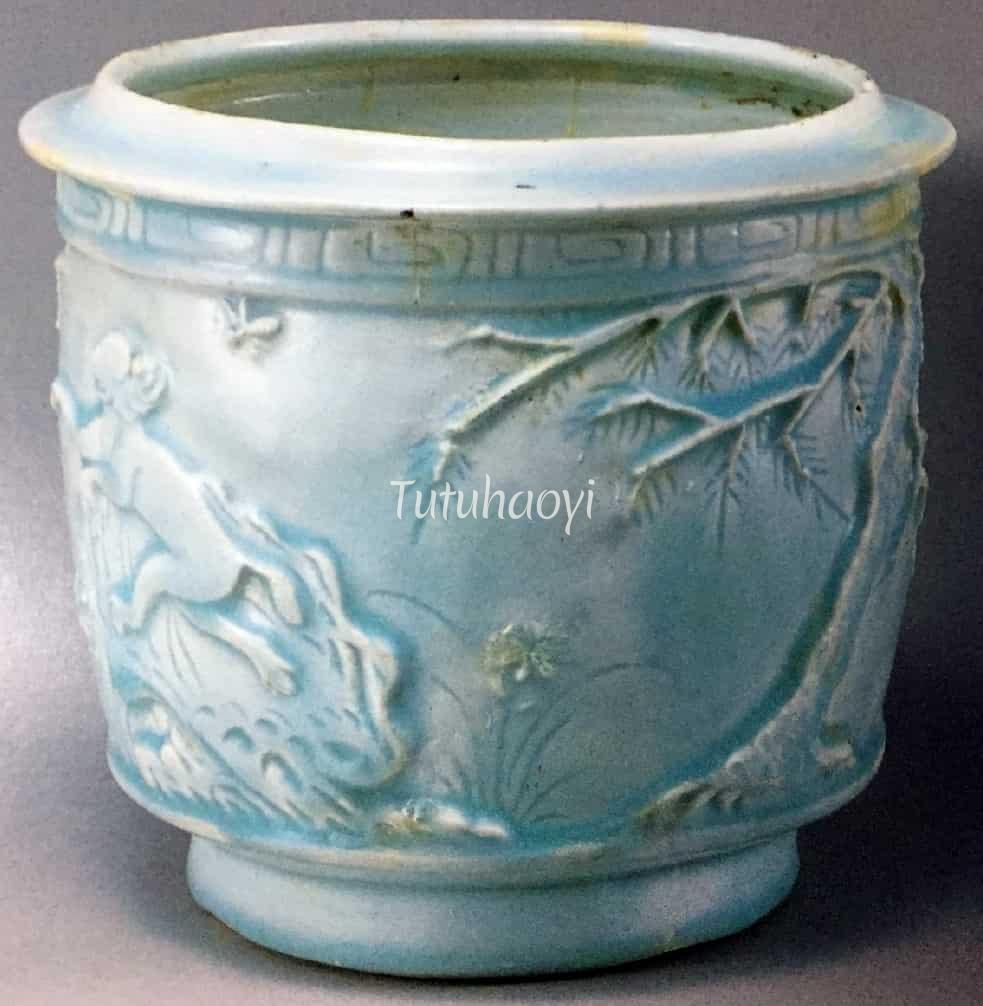

image above: brick-carving, Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

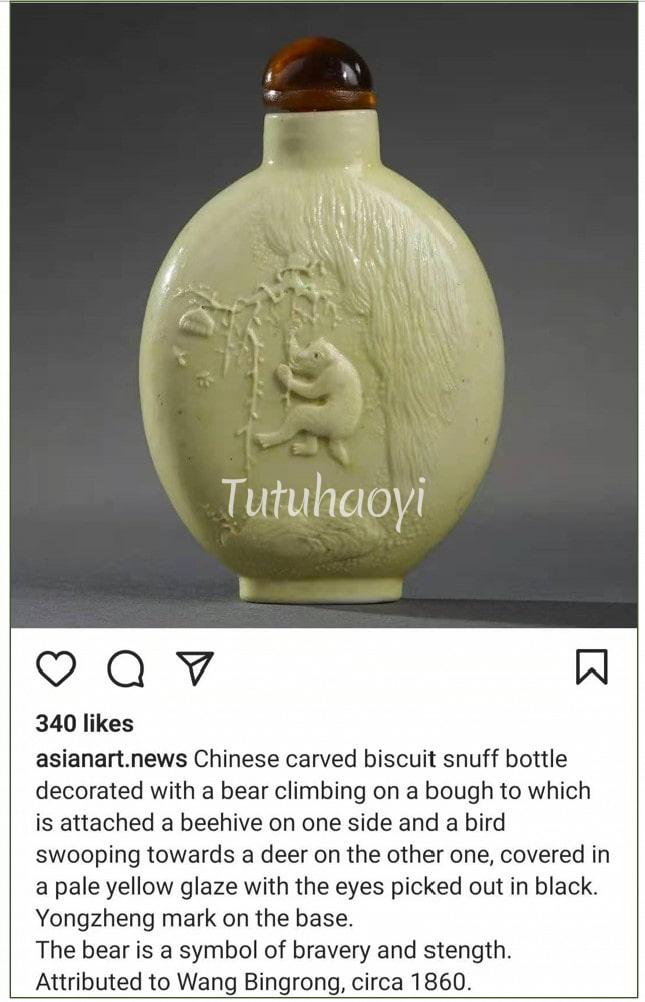

There is a late-Qing Chinese porcelain snuff-bottle advertised by Galerie Bertrand De Lavergne, Paris and in the online magazine @asianart.news. The description of the motif carved on it in shallow relief given goes like the following: ‘…a bear climbing on a bough to which is attached a beehive on one side and a bird swooping towards a deer on the other one…’

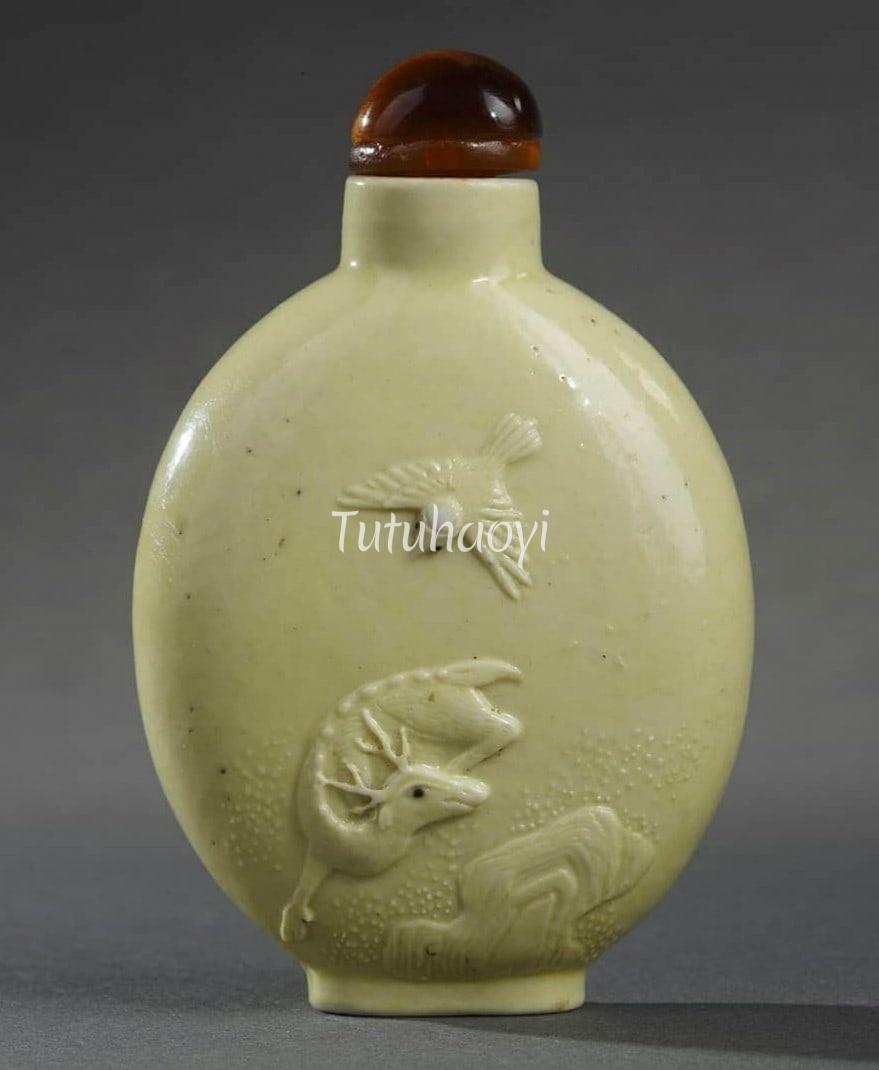

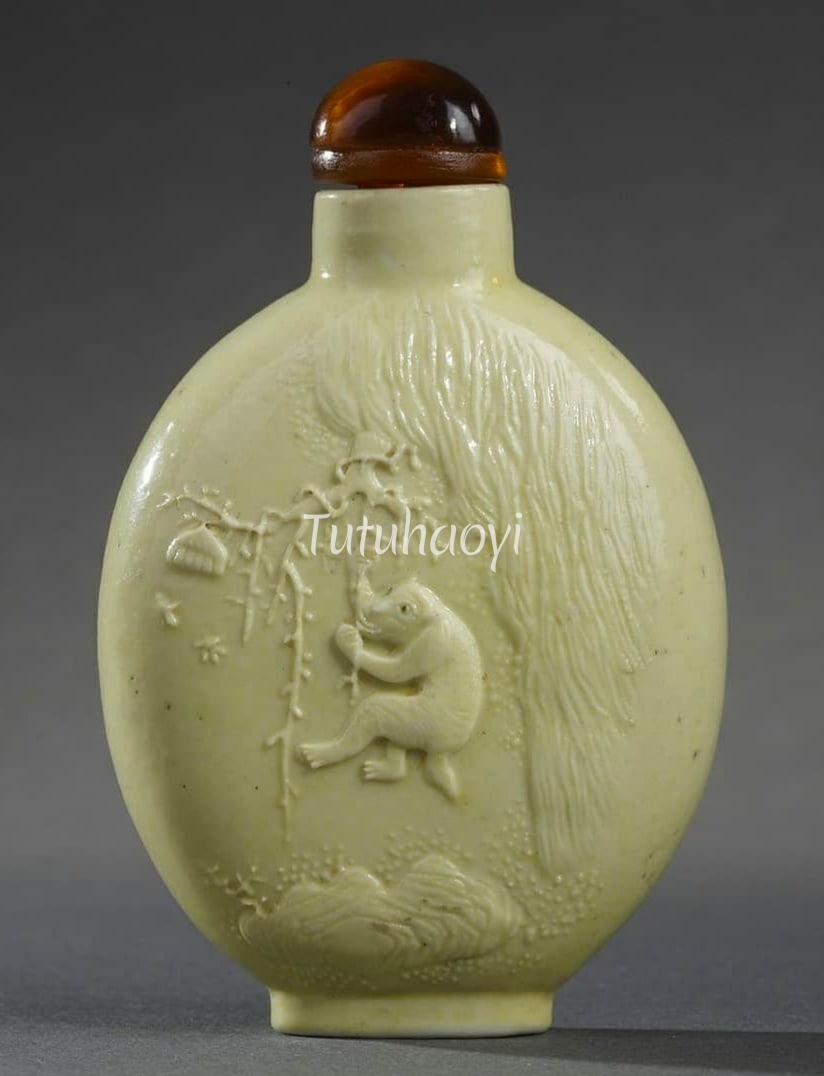

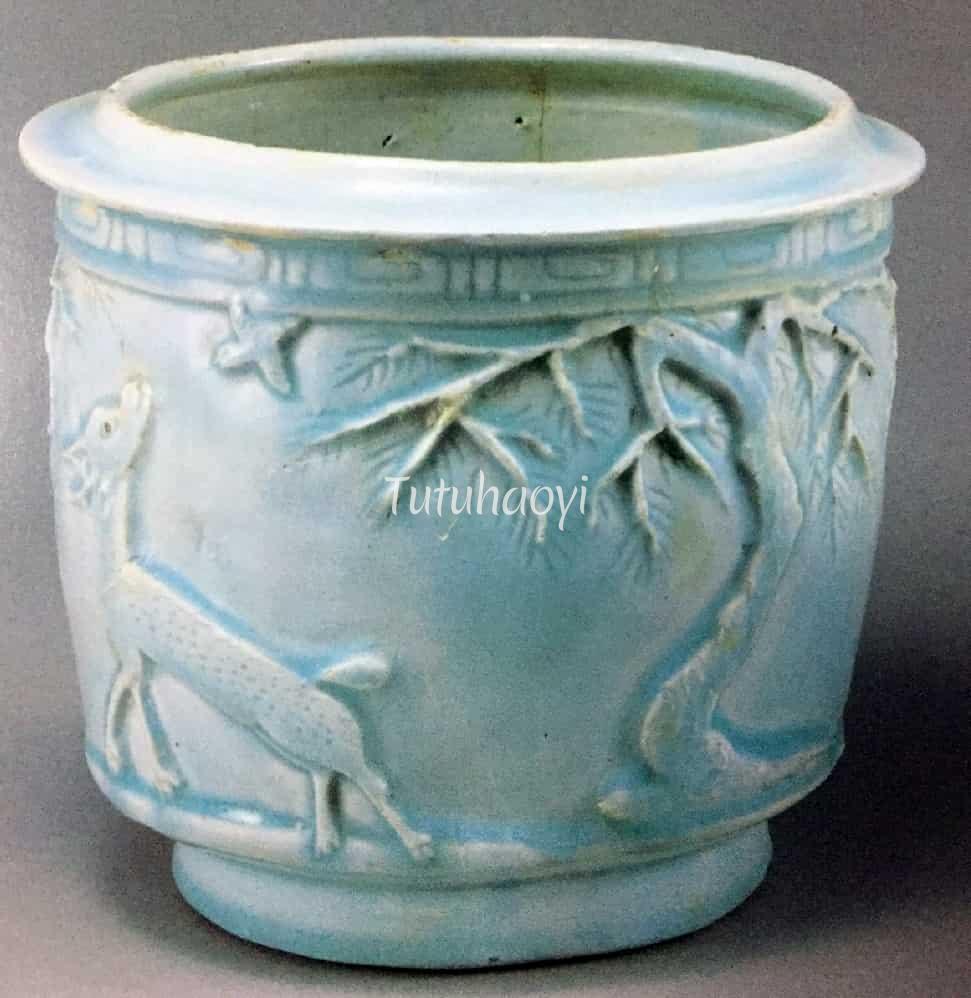

People from a culture where Fables of Aesop were their childhood bedtime stories may easily associate the chubby creature near the swooping bees with the hot-tempered and unwise bear. However, the animal motif encircling the snuff-bottle is deeply rooted in the traditional Chinese culture and its interpretation and appreciation require a totally different set of ‘eyes’. This particular pun rebus composition is conventional and culturally specific, consisting of four essential pictorial elements: bird, deer, bee, and monkey. They combine to convey the auspicious message of ‘May you be created a peer and earn a handsome official income’. Curios bearing such motifs were treasured gifts passing among friends and colleagues to lubricate the social machinery.

This is how this Chinese pun rebus works. The word ‘que 雀’ for ‘small bird’ in Chinese puns on the word ‘jue 爵’ for ‘high official rank’ or ‘peerage’. The word ‘lu 鹿’ for ‘deer’ shares the same sound with ‘lu 禄’ for ‘emolument’ or ‘salary’. The word ‘feng 蜂’ for ‘bee’, is a pun on ‘feng 封’ for the verb ‘to be granted’ and the word ‘hou 猴’ for ‘monkey’ is a pun on ‘hou 侯’ for ‘marquis’, which represents high ranks in the government in general.

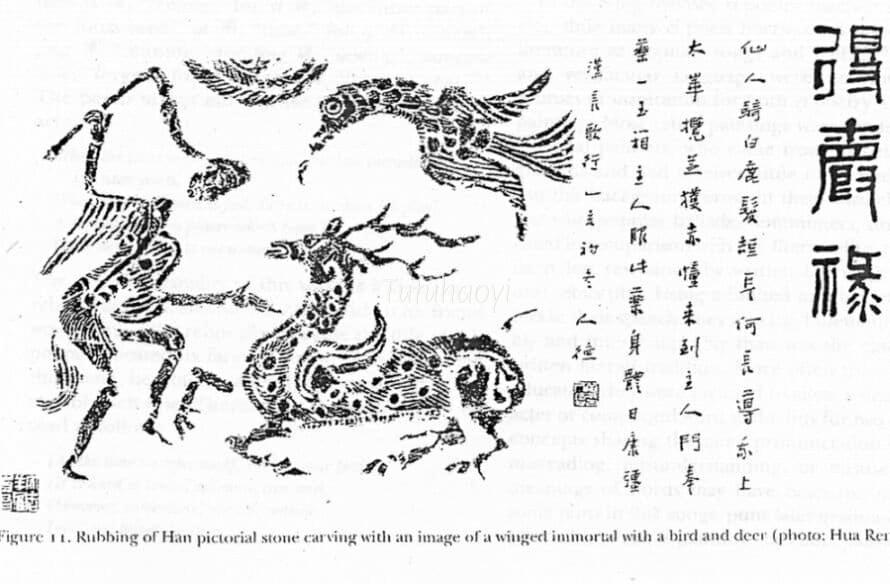

The juxtaposition of flying birds and roaming deer has been used to represent people’s dream of climbing high on the social ladders ever since the Han dynasty (202 BEC – 220 CE), as is vindicated by a carving stone rubbing kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. The seal script caption on the right-hand side says ‘Acquiring Peerage Titles and Official Emoluments’, which indicates that ancient Chinese people endorsed the received meaning of this zoomorphic motif.

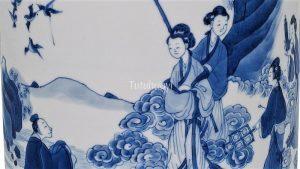

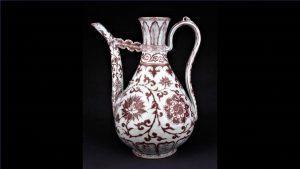

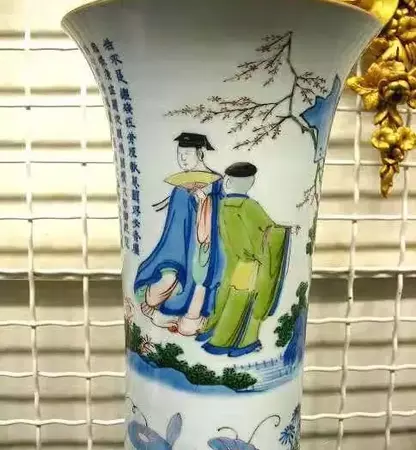

Further examples of different renderings of the same motif appeared in large numbers in late Ming and early Qing (ca. 1550–1720) periods. The living creatures are often arranged on a flat plane with not much attention paid to their relative sizes as long as the essential elements are present, with usually enlarged bees and birds and dwarfed deer. On some a narrative event is introduced where the usually curious monkey is portrayed as trying to disturb bees or poking the beehive. In the context of such a pictorial tradition with ample evidence on different media, serving people from different social and economic strata, the somewhat plump creature on the 1860s snuff bottle has to be a monkey, rather than a bear albeit the porcelain carver’s skill leaves something to be desired.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.