Editor: Have you ever wondered why images of an old scholarly man riding an ox are depicted on Chinese antique porcelains and scroll paintings? What is so special about this man who looks highly respected and followed by yet still sitting on a buffalo’s back? In fact, this prominent figure is Laozi, a legend who has influenced Chinese history and philosophy for thousands of years. We hereby invite Dr Yibin Ni to highlight the great works and important events of Laozi, illustrated with traditional artworks left by our ancestors.

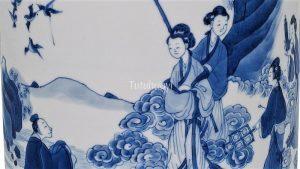

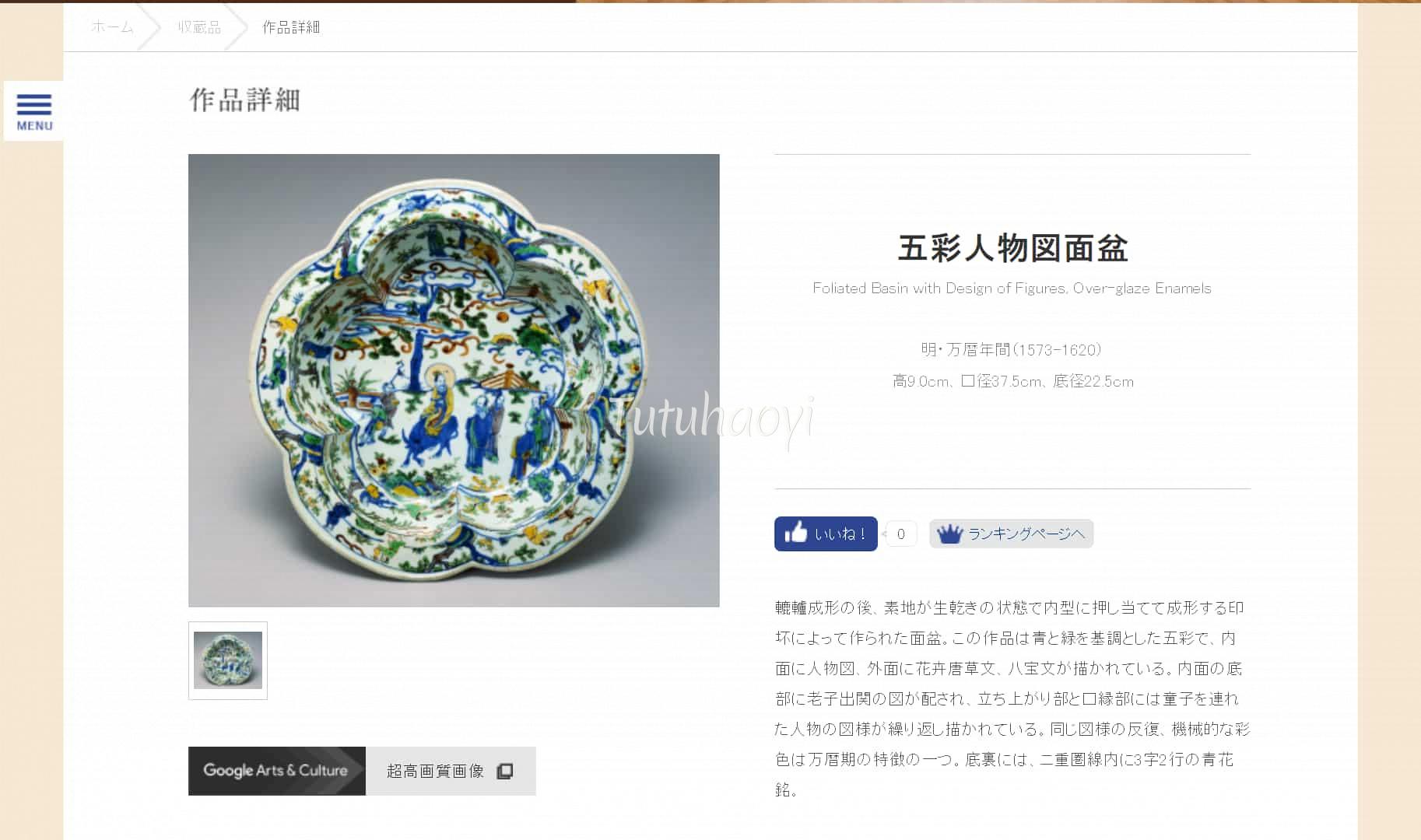

image above: porcelain basin with enamelled decoration (detail), Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, courtesy of Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, Japan

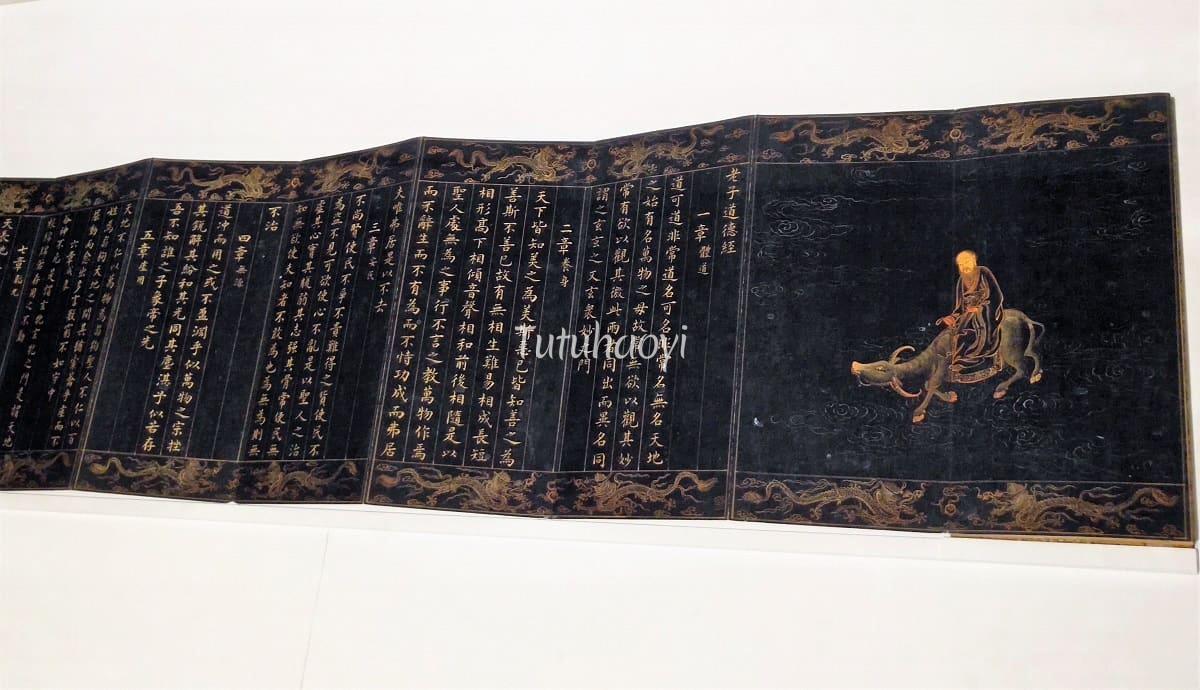

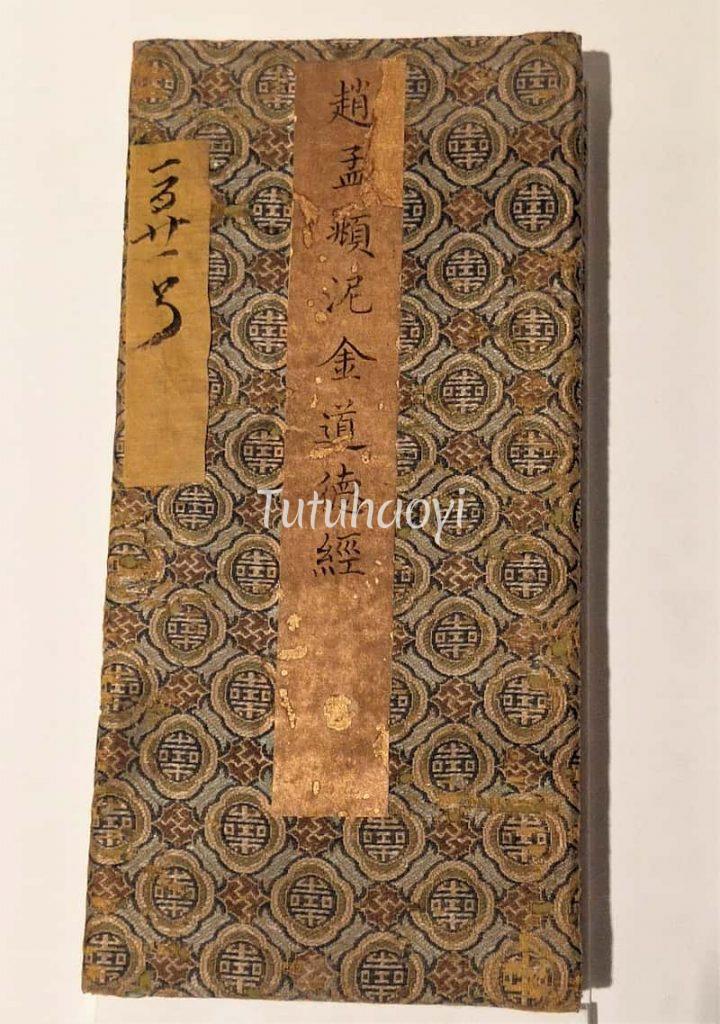

Laozi (Lao Tzu) 老子, literally ‘old teacher or master’, is the well-known name for a great ancient Chinese thinker, to whom a five-thousand-character book ‘Dao de jing 道德经’, or The Scripture of the Way and Virtue, has been attributed. He is regarded as the founder of philosophical Daoism (Taoism), daojia 道家, because of his profound insights to life and the world, and a supreme deity in religious Daoism (Taoism), daojiao 道教, and popular Chinese religious cults.

Ancient literature shows that Laozi served as the Keeper of the Imperial Archives of the Eastern Zhou court (东周 770-258 BCE). He must have greatly benefited from the perk of the job – the easy access to the best stock of classics written on bamboo slips at the time and became so learned that even Confucius (551-479 BCE), the paragon of the Chinese sages, consulted him several times on matters concerning rituals of mourning and funeral and spoke very highly of him.

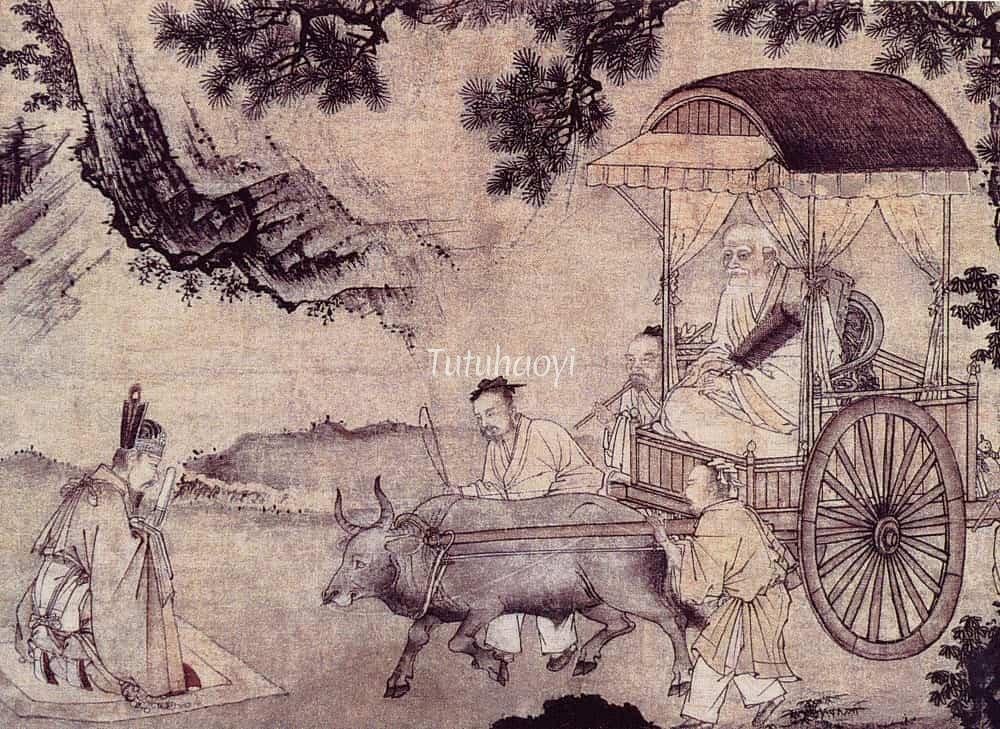

Legend goes that Laozi grew unhappy about the moral decay and decline of the society and decided to leave for the unsettled frontier in the west. A noble lie says that Yinxi (尹喜), the official in charge of Han’gu Pass (函谷关) on the border saw some purple clouds flying towards his direction, just as the wise men saw the Christmas Star rising over Bethlehem, and then euphorically expected and welcomed the renowned master’s arrival. Yinxi managed to persuade the master to write down his wisdom before he began his new life as a hermit. The brief pamphlet, also named after its author as ‘Laozi’ before ‘Dao de jing’, enjoyed a long-lasting appeal, resulting in more than seven hundred commentaries devoted to it by men of letters throughout the long history of China.

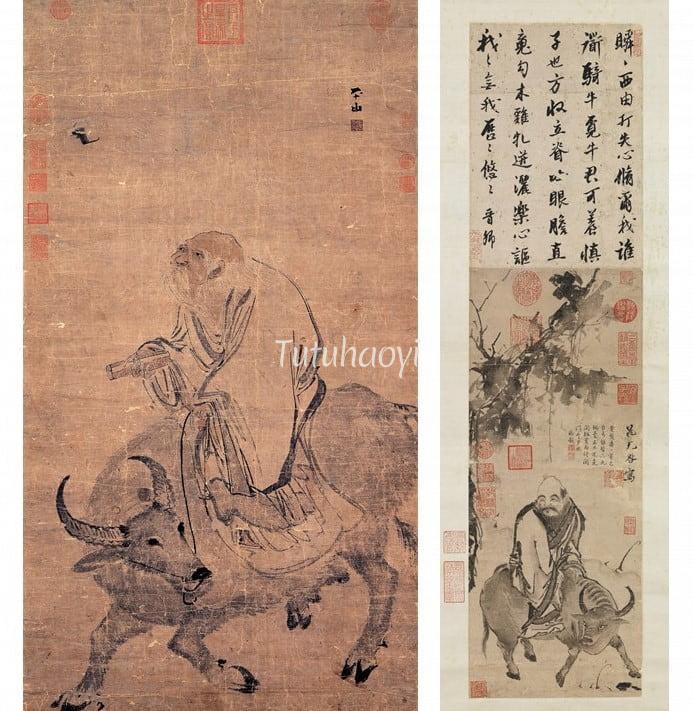

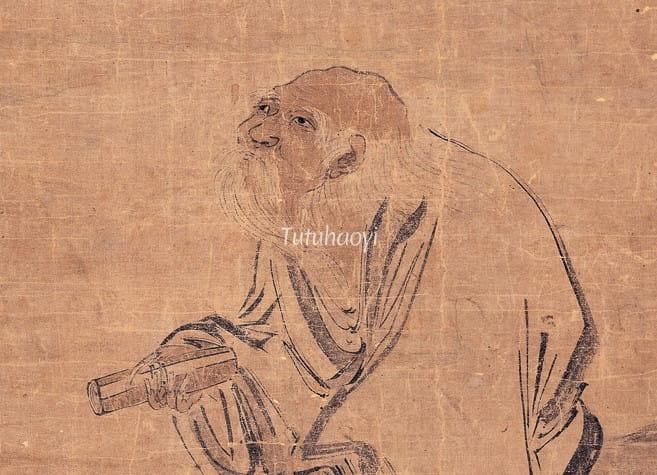

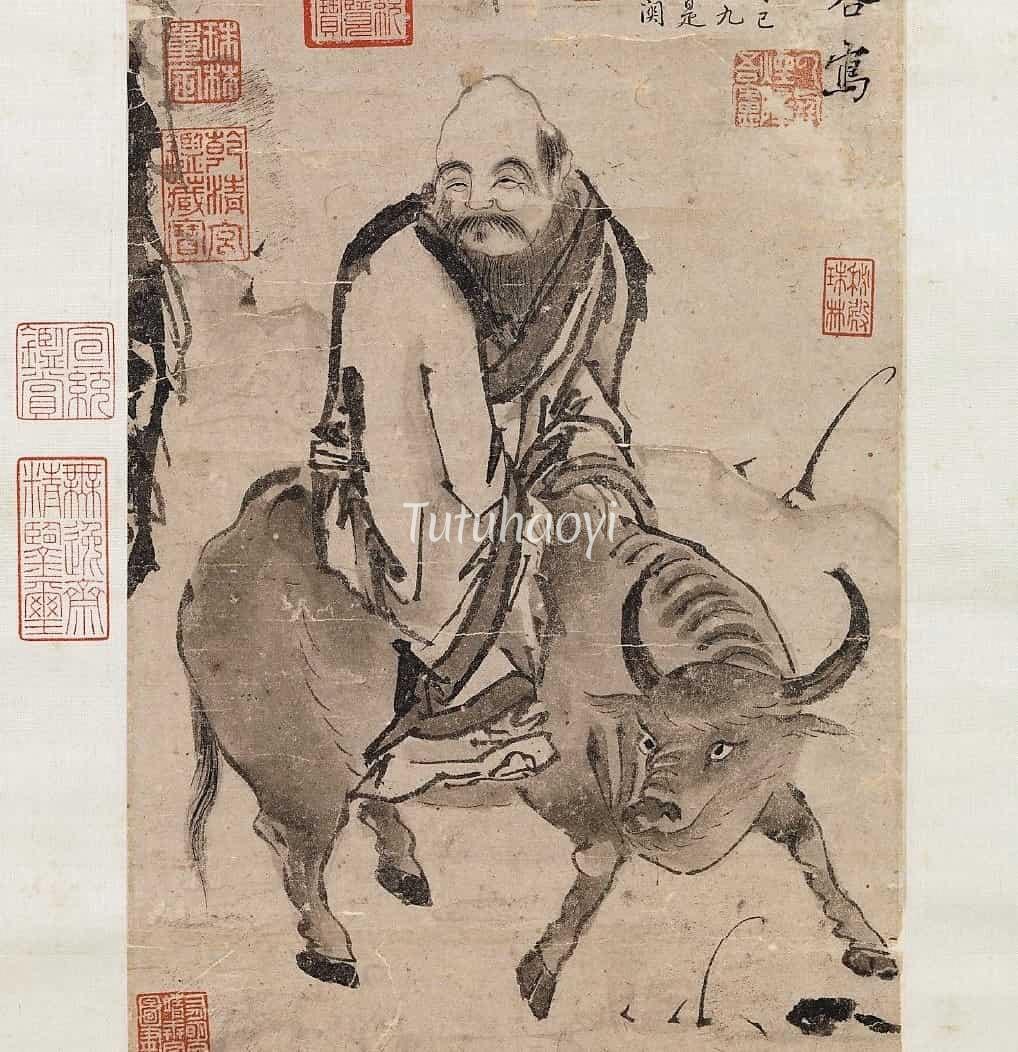

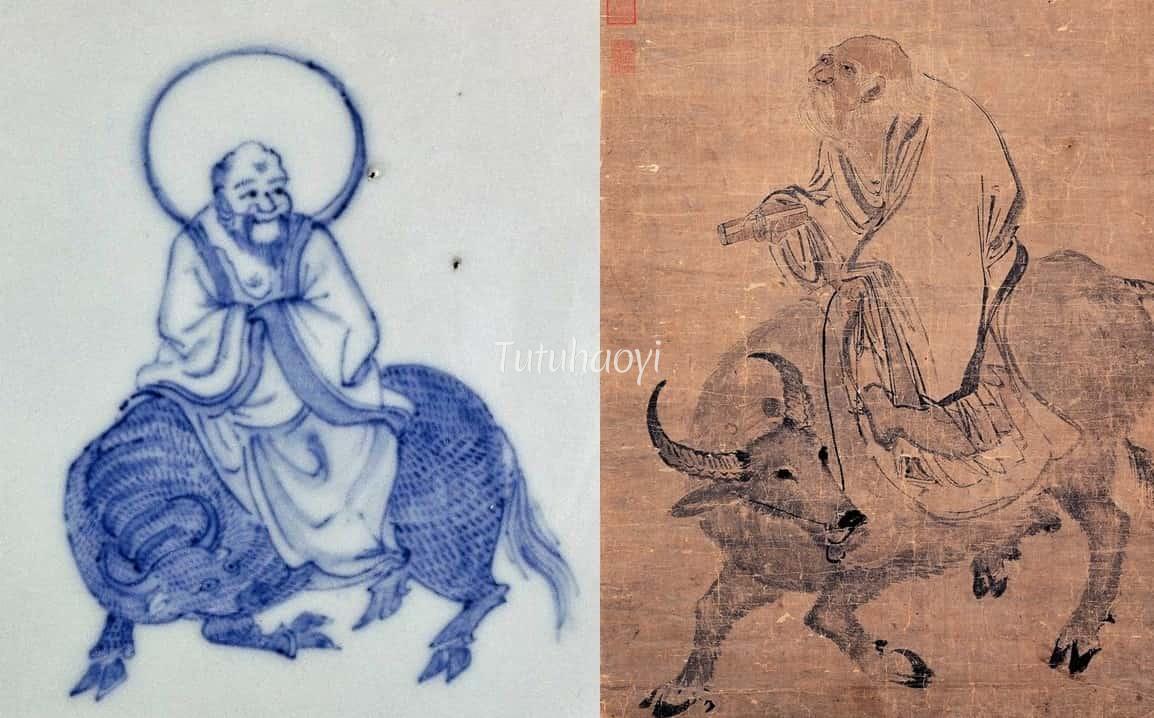

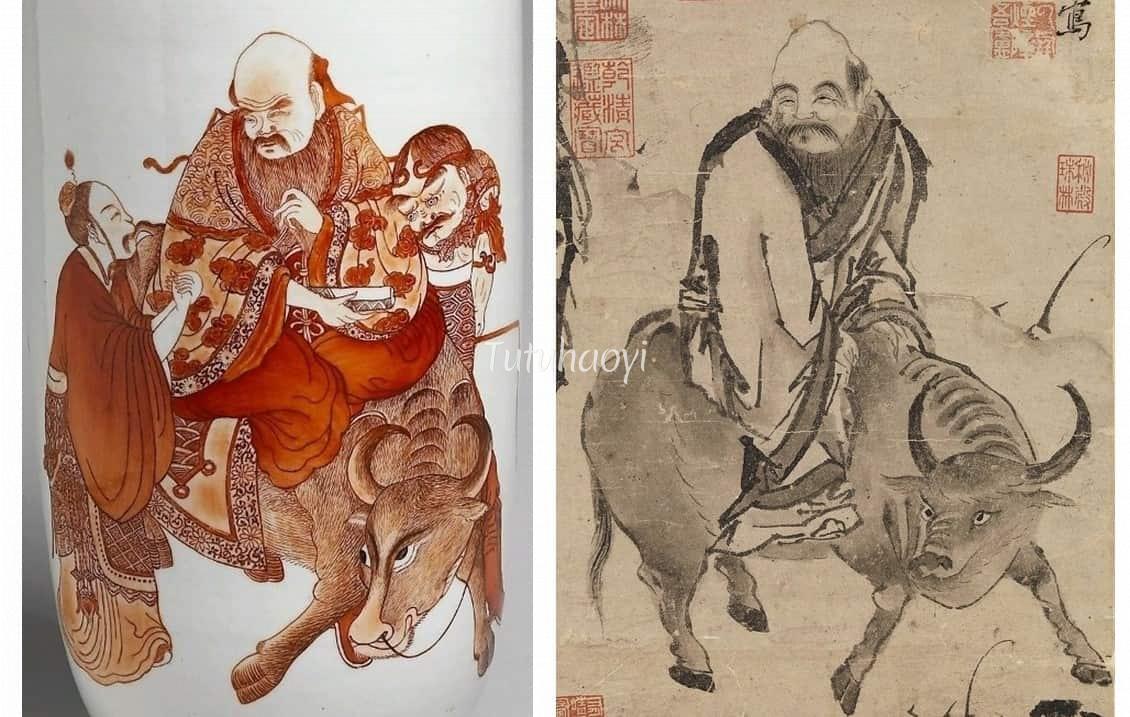

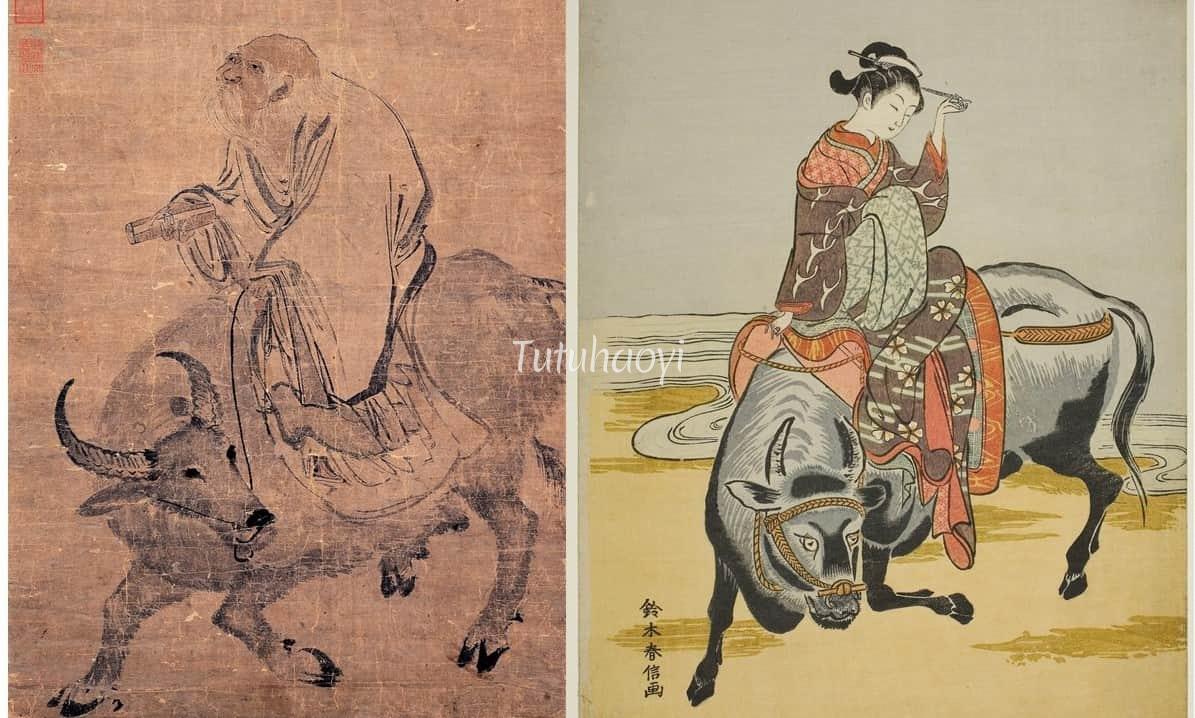

The earliest images of the legendary figure can be traced back to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) when he was typically portrayed as a geriatric riding on the signature buffalo, as are found on two hanging scrolls, one by the Zhe-school painter Zhang Lu 张路 (ca. 1464-1538) and the other spuriously attributed to Chao Buzhi 晁补之 (1053–1110), a Song-dynasty literary man. In the former, Laozi is holding a scroll in his right hand, presumably representing his seminal work. In the latter, Laozi is depicted as a stout character, which later became Laozi’s more formal persona.

A blue-and-white square tile fired during the Wanli period (1573–1620) is embellished with an elegant depiction of Laozi built up by fine lines and numerous short strokes that resemble the buffalo’s hair. A halo behind the master’s venerable bald head indicates his deity status. The buffalo head jack-knifed towards its left side, its right leg strode forward, while its left hoof bent backward. The posture of the bovinae is a twin brother of that in Zhang Lu’s scroll and this resemblance calls for the possibility that there had been a common model shared widely by artists at the time.

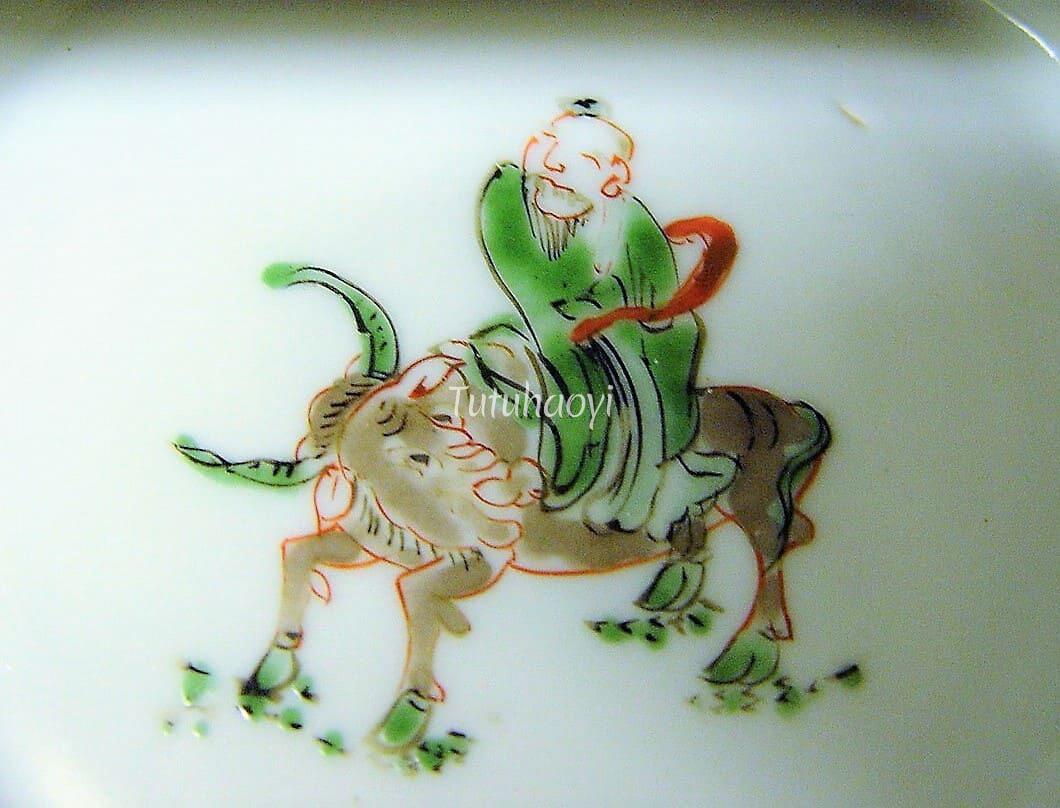

An overglaze enamelled cartoon figure of Laozi riding on a buffalo is found on a late-Ming dish potted during the early part of the 17th century. The lean figure resembles Zhang Lu’s rendering and so does the whole composition.

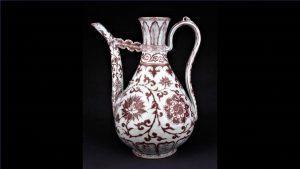

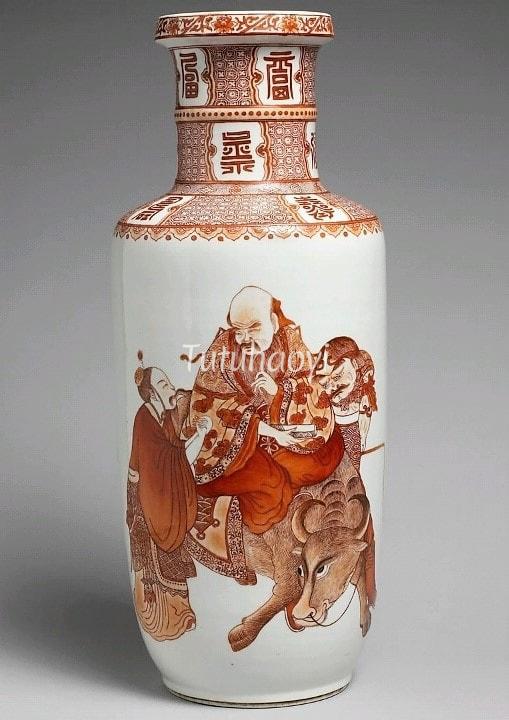

On the other hand, the Laozi on an iron-red enamelled rouleau vase follows the style of the ‘Chao Buzhi’ scroll, with a stocky figure and egghead and his buffalo’s head both turn right. He is met by the official in charge of Han’gu Pass, and attended by a non-Chinese servant, a subtle reference to the western barbarian land of Laozi’s destination.

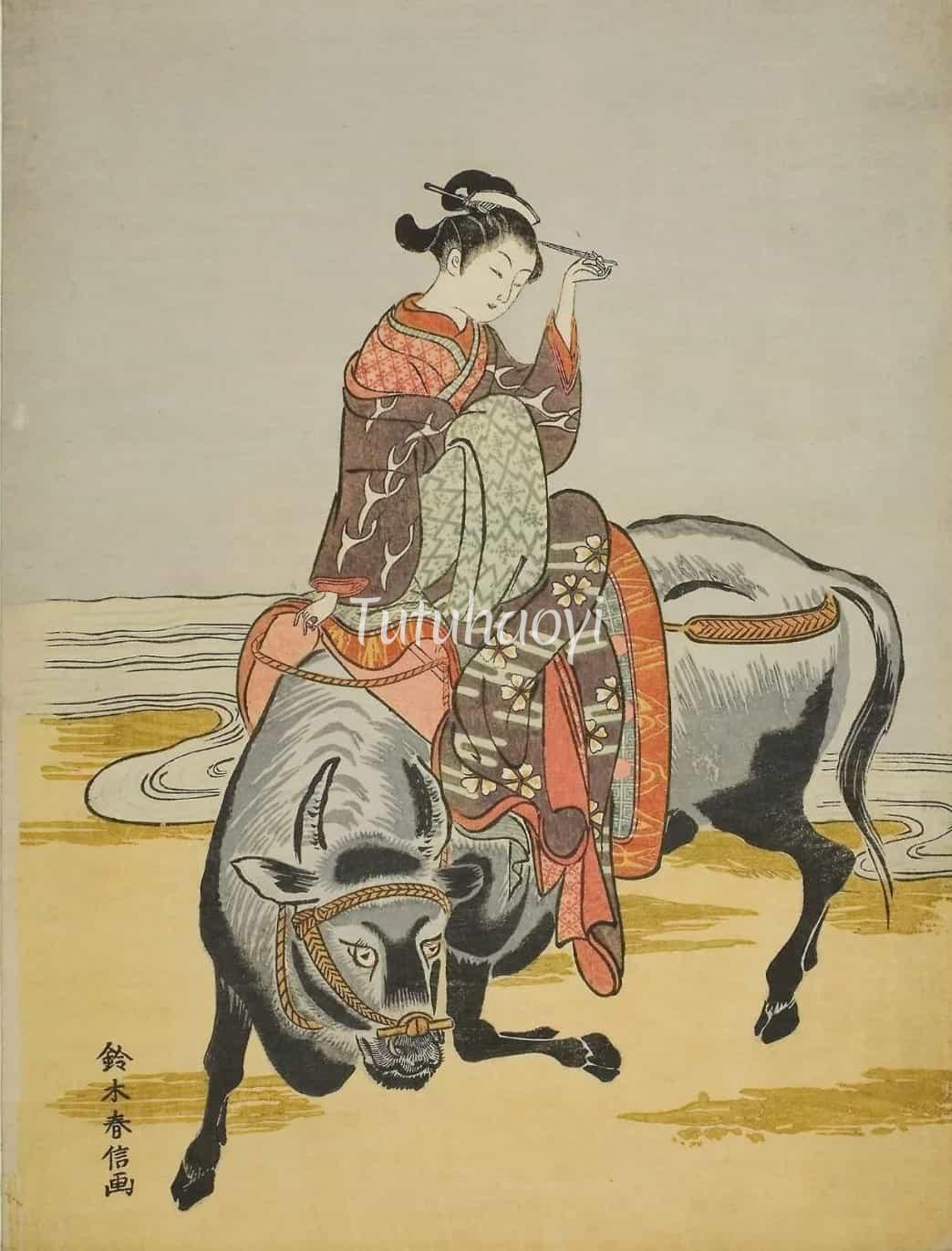

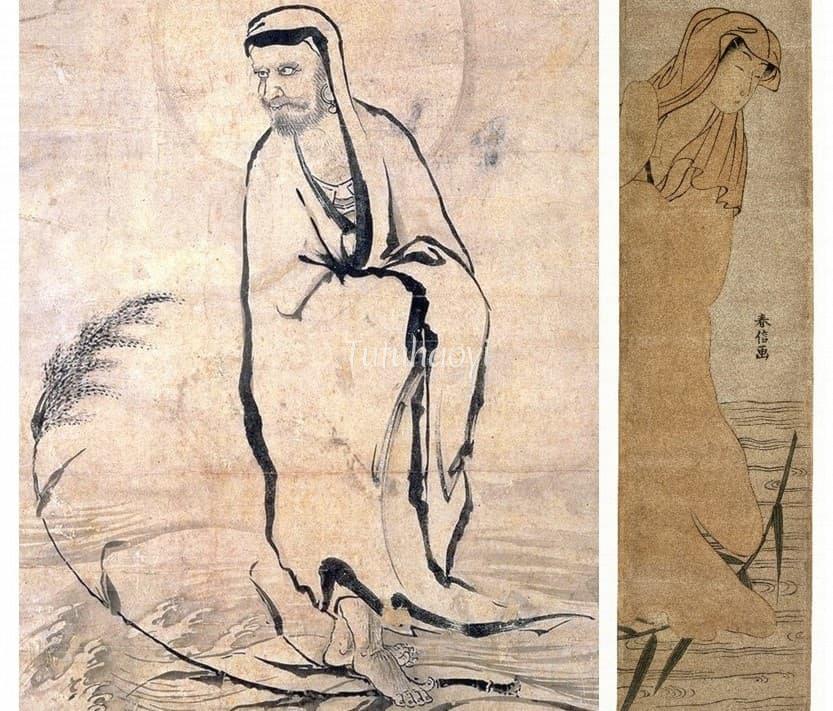

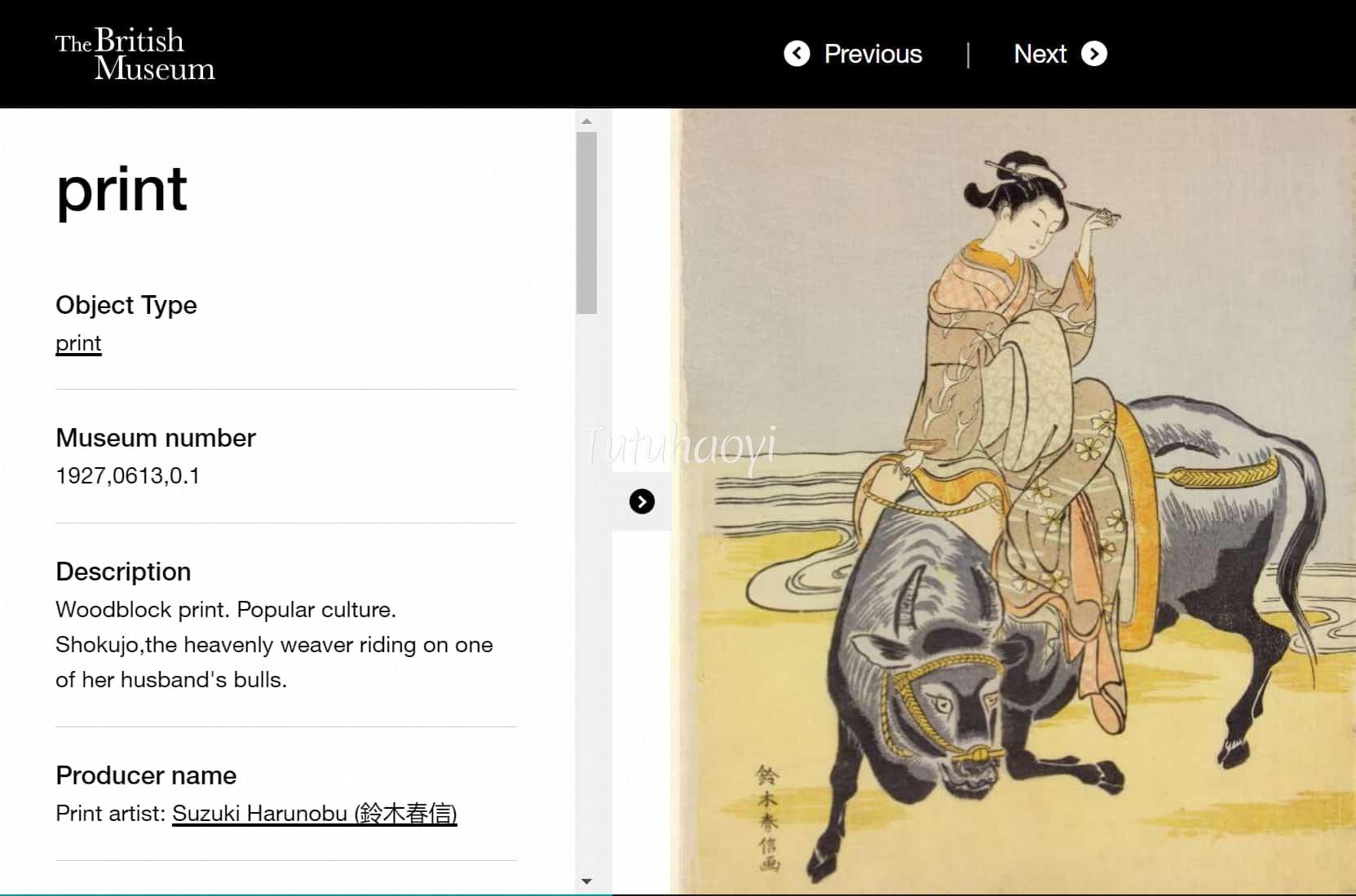

The way Zhang Lu characterised the buffalo was obviously inherited by Suzuki Harunobu 铃木春信 (ca. 1725–70) in Japan in a mitate-style print, on which a lavishly dressed geisha courtesan was substituted for the octogenarian. Such a pictorial parody was created as an intellectually stimulating game for the educated elite of the time. Related examples include parody images of ‘Bodhidharma crossing the Yangtse River on a reed 达摩一苇渡江’ and ‘The Immortal Qingao Riding a Fish 琴高乘鲤’, where both the revered legends were replaced by a female beauty.

The cracking of the visual riddle requires encyclopaedic knowledge of Chinese and Japanese traditional culture, which has been proven to be a challenge in the contemporary world. The label on the print in the catalogue of the Art Institute of Chicago is ‘Courtesan riding an ox’ and that in the British Museum is ‘the heavenly weaver riding on one of her husband’s bulls’. The identification of the theme of the print remains to be a controversy, as is reflected in the online talk given by Dr Matsuba Ryoko 松葉涼子 in early 2021.

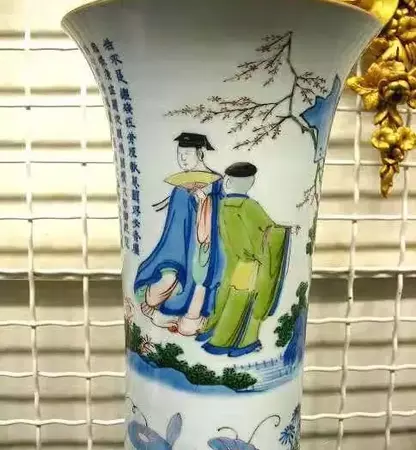

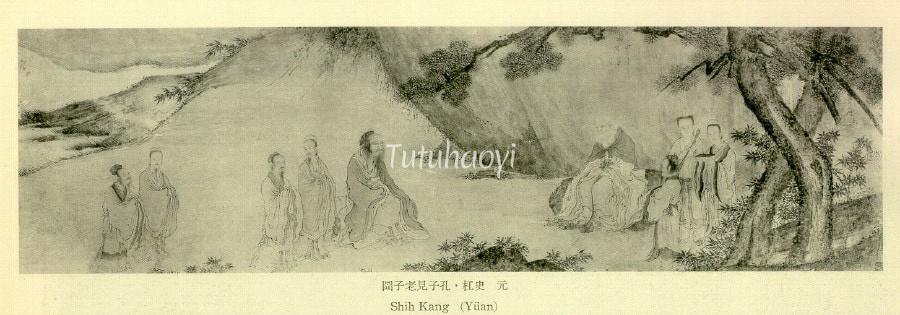

The legendary meeting between Laozi and Confucius was first pictorially presented during the Eastern Han period (东汉 25–220 CE), in which the two sages were usually bowing to each other with the precocious boy prodigy Xiang Tuo 项橐 standing between them. However, this early simple characterisation of the famous meeting was taken over by a new composition of the two literary giants surrounded by their own pupils and servants in late imperial China. One surviving early example attributed to the Yuan painter Shi Gang 史杠 (active around 1352) staged the conference among huge jumbles of rocks in an austere landscape.

In the bottom of a Ming wucai (five-coloured) basin in the collection of Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, there is a scene which the museum labels as ‘Laozi exiting (Han’gu) Pass’. However, the elderly master talking to Laozi on the buffalo back is much older than the usual depiction of Yinxi, the guarding official of the Pass, and looks like a sage rather than a petty official. The standing sage is followed by several confident, respectable-looking gentlemen, quite different from those servant-like figures behind Yinxi in Shang Xi 商喜’s history painting of ‘Yinxi welcoming Laozi at Han’gu Pass’. These gentlemen obviously resemble Confucius pupils in Shi Gang’s painting of ‘Confucius consulting Laozi’. Thus, this scene is that of the meeting between the two ancient masters rather than that of Laozi exiting Han’gu Pass.

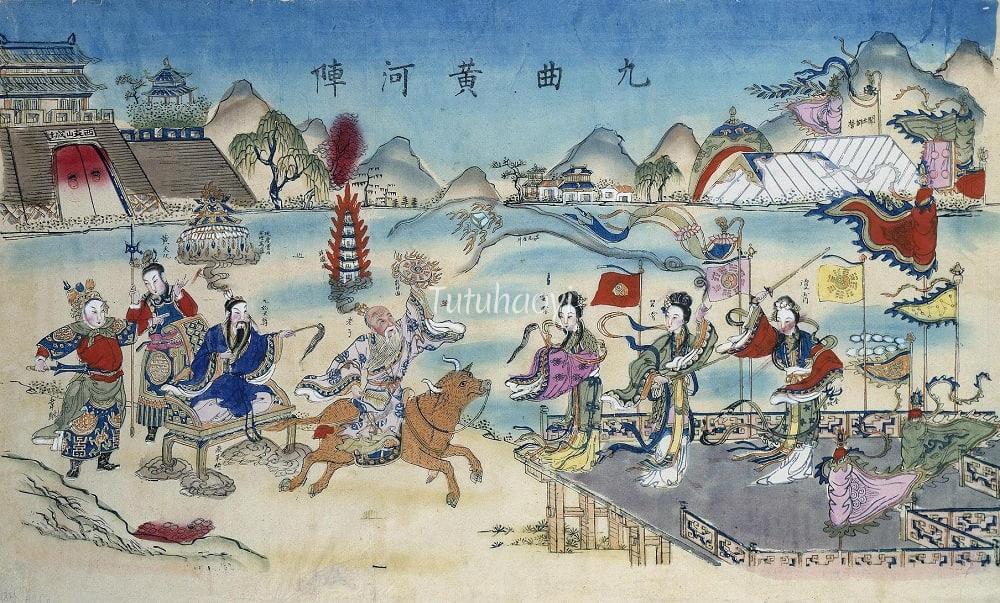

Laozi’s supreme status in the Chinese popular pantheon is highlighted in The Creation of the Gods (封神演义), a major work of vernacular literature published at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. In Chapter 50 of the novel, the baddies led by three extremely powerful women created a battle formation called ‘Yellow River Nine Zigzags (九曲黄河阵)’ and trapped almost ninety percent of the heroes. It was Laozi who single-handedly reversed the situation. A Kangxi-period new-year print made almost a century later than the novel’s publication records the contemporary artistic imagination.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.