Editor: ‘Wu Song slaying the tiger’ is a popular fictional story among Chinese people. It was first recorded in 13th century, and gained its fame after being further adopted in plays and novels in Ming dynasty. However, it’s hardly noticed that this story scene has been chosen in Chinoiserie decorative art in Europe. Here is Dr Yibin Ni’s interesting research and his unique insights.

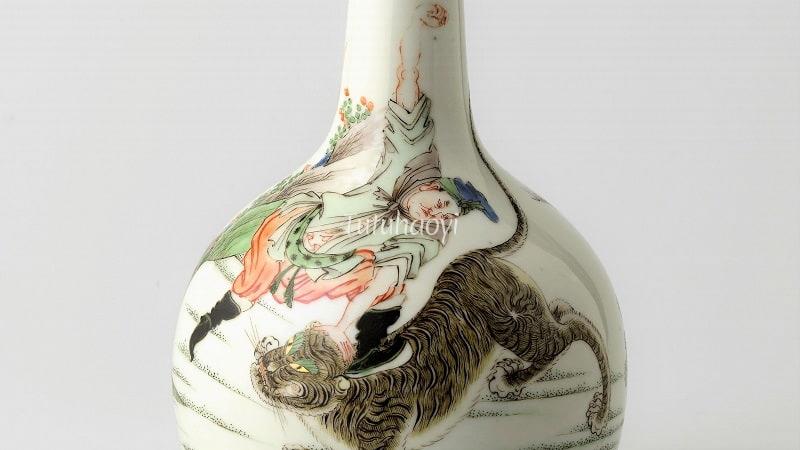

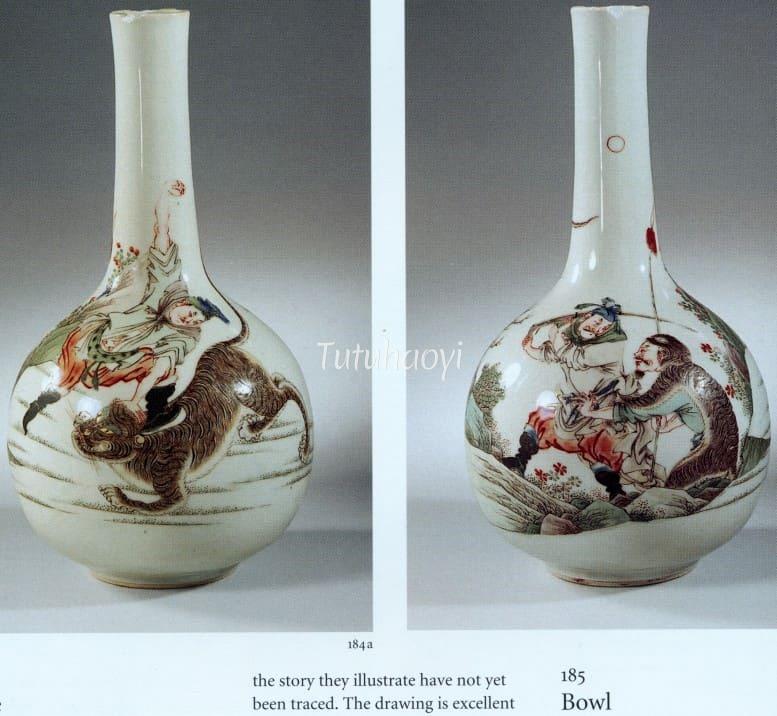

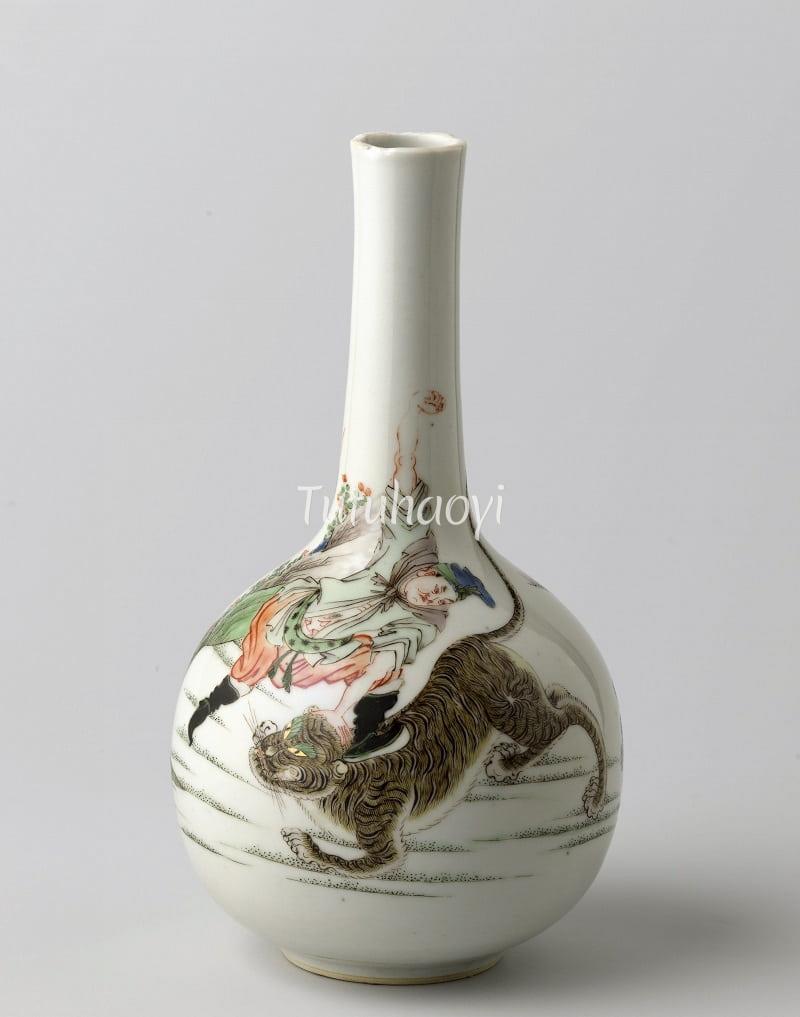

image above: porcelain bottle vase with overglaze enamelled decoration (detail), first quarter of the 18th century, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Nicknamed xingzhe (行者), ‘Pilgrim’ or ‘Traveller’, Wu Song (武松) is a popular fictional figure well-known for his slaying a tiger single-handedly after he was intoxicated on local rice wine. His heroic deed was first recorded as a title of a play in The Register of Ghosts (录鬼簿 Lugui bu), compiled by Zhong Sicheng (钟嗣成 ca 1279 – ca 1360). The book is a bio-bibliography of dramas and dramatists and lists the play entitled Wu Song Slaying a Tiger Even After His Quarterstaff Was Broken (折担儿武松打虎). During the sixteenth century, the legendary tiger-slaying episode was adopted in Shen Jing’s (沈璟, 1553–1610) miraculous play (传奇 chuanqi) The Story of the Righteous Knight-Errant (义俠记 Yi Xia Ji) and the two great classical novels in Chinese literature, i.e. The Water Margin (水浒传 Shui Hu Zhuan) and The Plum in the Golden Vase (金瓶梅 Jin Ping Mei).

During a trip, Wu Song entered a tavern at the foot of Jingyang Ridge (景阳冈), to have a break. The shop owner was proud of the potency of his alcoholic beverage and warned his customers not to drink more than three bowls and go alone to the territory of a man-hunting tiger in the mountains. Wu Song ignored his advice and proceeded with his journey even after drinking eighteen bowls of the rice wine. Sure enough, in the bushes, Wu Song was ambushed by the hungry tiger and shocked out of his stupor. After an arduous primaeval confrontation between man and nature, Wu Song subdued the mighty beast. On his way out, Wu Song met some local hunters who had been trying to eliminate the monster and they treated him with awe and respect. His Gilgamesh-like feat won him the honour of being the local hero and the story passed on everybody’s lips with numerous adaptations in arts.

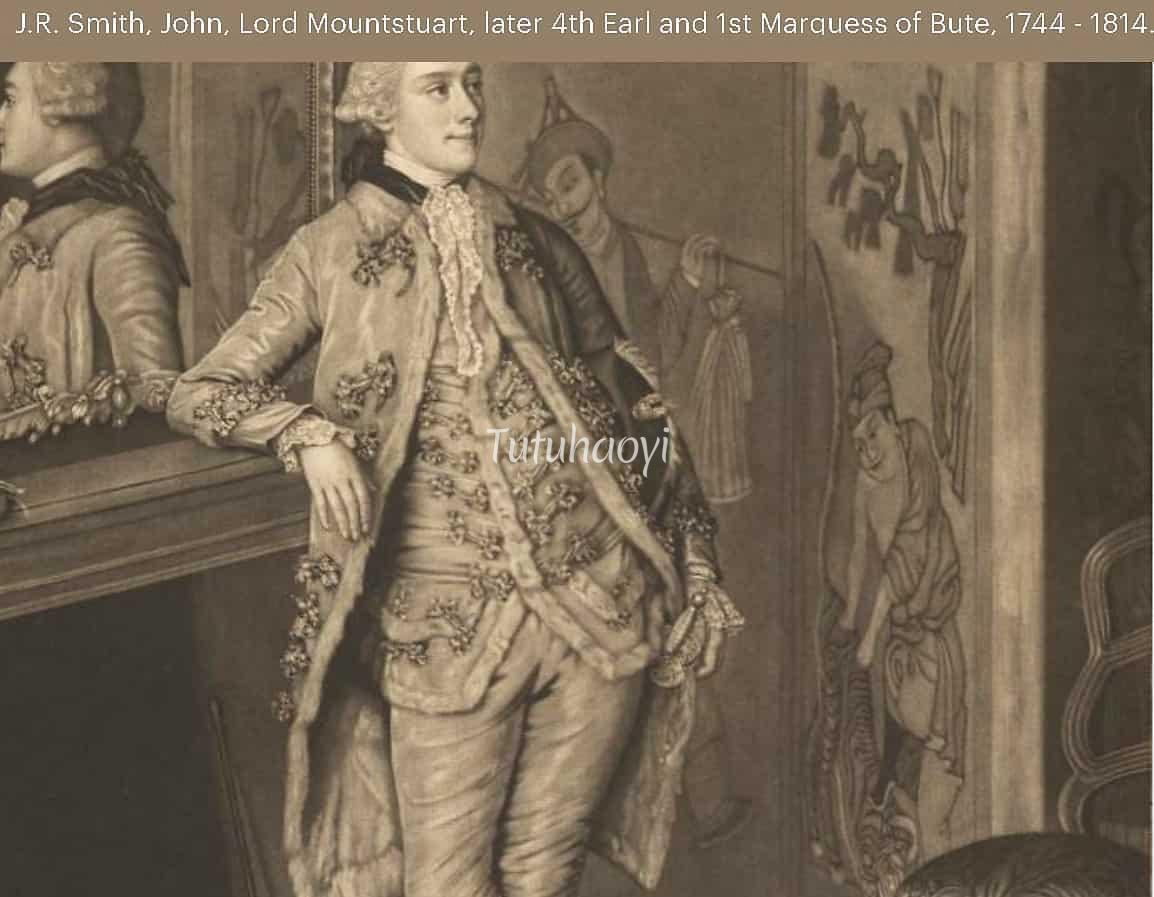

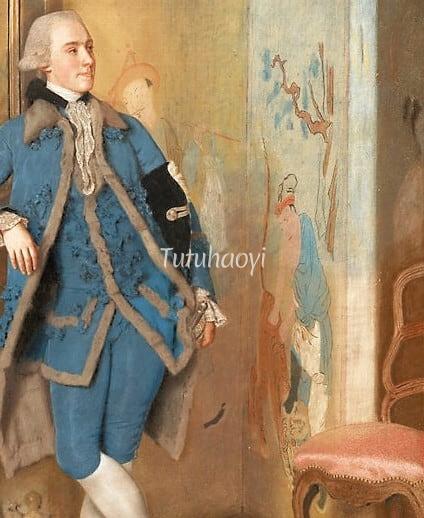

The eighteenth century saw the popularisation of the chinoiserie decorative style in Europe and Europeans held fascination and respect for things Chinese delivered by the recently-established sea trade route. The portrait of the diplomat and collector John Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute (1744–1814), in the National Portrait Gallery, London, reveals a detail of the legendary scene of Wu Song slaying the tiger on a hand-painted Chinese wallpaper on the panel of his grand family mansion.

Millions of visitors may have passed the two imposing portraits of Lord Mountstuart in the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the Getty Center, Los Angeles, respectively. But hardly any of them would have noticed the traditional Chinese story scene embedded in the portraits. The depiction of the actual chinoiserie hand-painted wallpaper, in fact, serves as the historical evidence of a harbinger of the future globalisation.

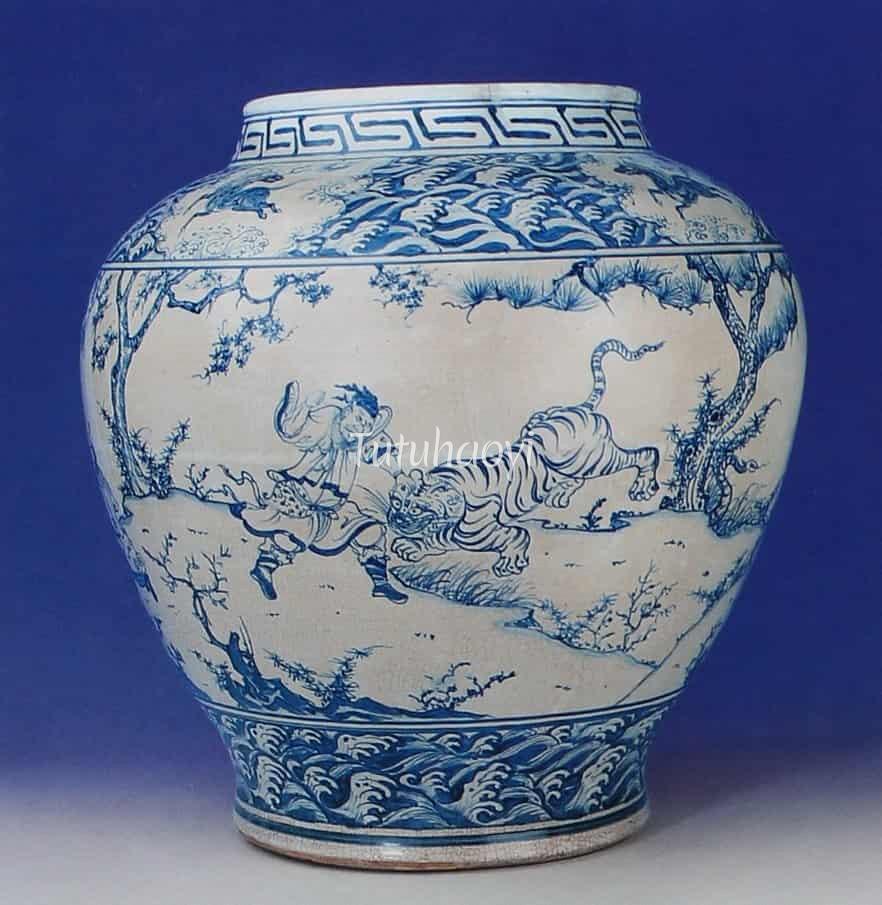

There is an 18th-century enamelled bottle vase bearing the scenes of the Wu Song story in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. However, Dr Christiaan J.A. Jörg admits in his catalogues that ‘The meaning of these lively scenes and the story they illustrate have not yet been traced.’ (Christiaan J.A. Jörg, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Ming and Qing Dynasties, the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1997, p. 168; current webpage of this vase in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam online catalogue). On one side of the vase, Wu Song is raising high his powerful right fist, with his left hand grabbing the tiger tightly by the neck and his left foot on its shoulders to further check the beast’s movement. The viewer can sense the tiger’s struggle against Wu Song’s might but his firm control over the beast is almost assured. On the other side, two local hunters, one of whom is disguised with an animal skin, are staying away from the fight.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.