Editor: Through analysing the elements of the traditional Chinese figures and story scenes on art collections, such as dressing, hairdo and composition of figures and their gestures, Dr Yibin Ni has compared a number of porcelain vessels from Ming and Qing dynasties, and demonstrated his unique insight which can facilitate the correct dating of Chinese antiques. A famous theme that depicts Bo Yi and Shu Qi Stopping the Zhou Army was adopted in the following discussion.

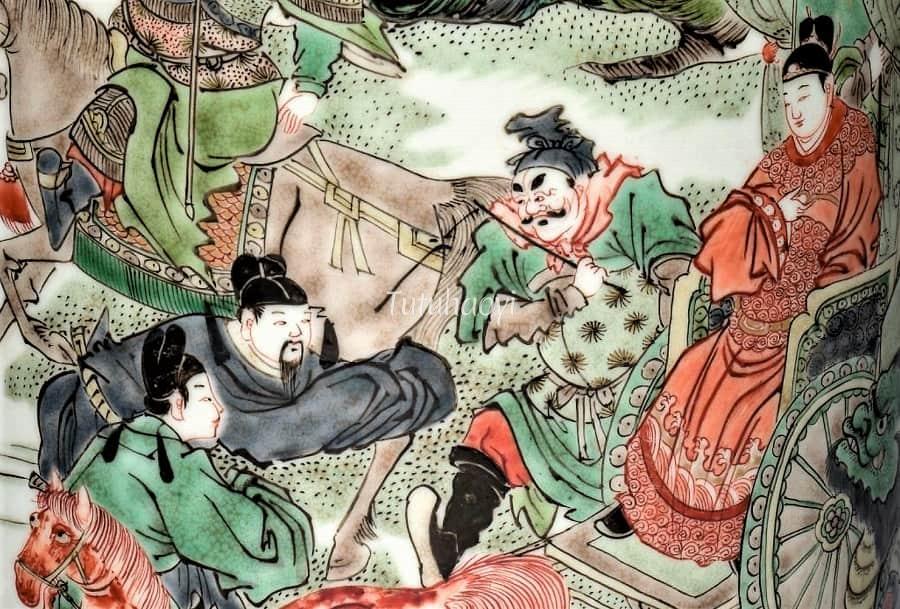

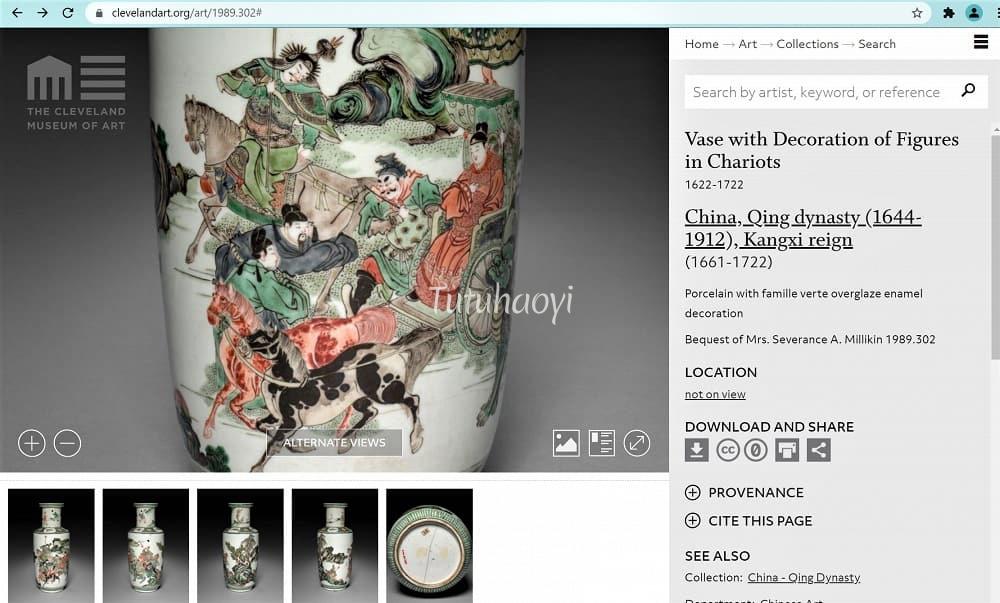

featured image above: porcelain vase (detail) with famille verte overglaze enamel decoration, Qing dynasty (1644-1911), courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

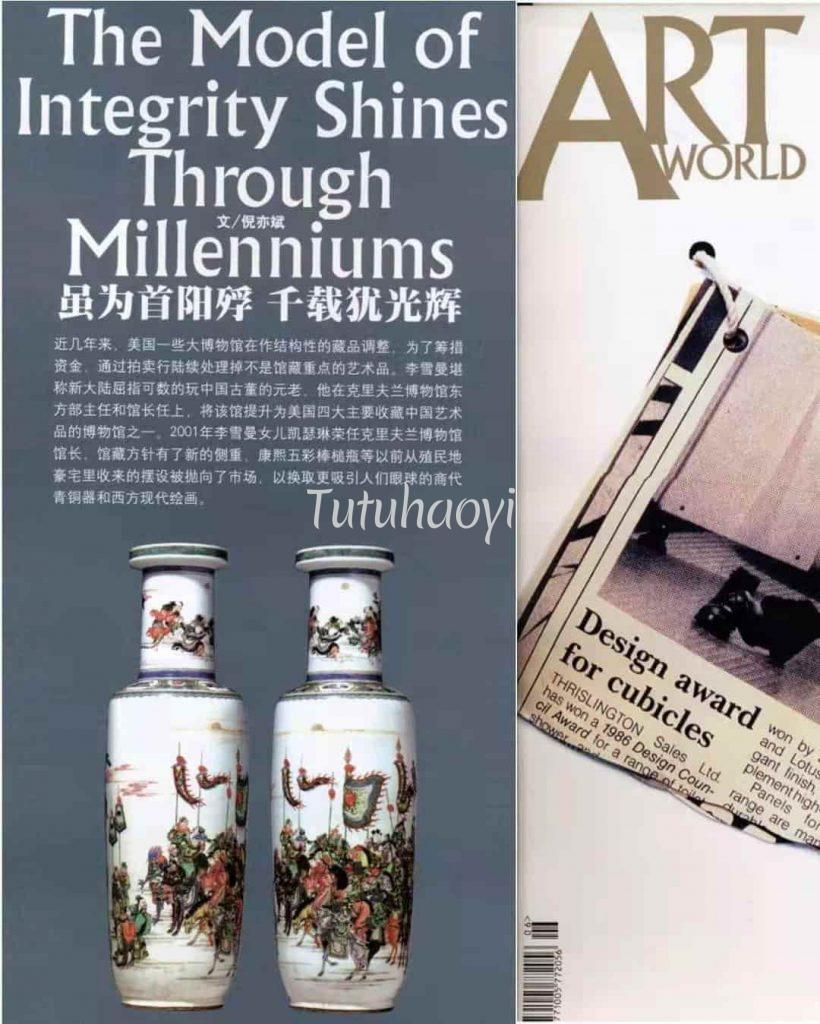

If you find these pictures familiar and, furthermore, you can recognise they are the story scenes of ‘Bo Yi and Shu Qi Trying to Stop the Mighty Zhou Army’, then you are pretty well-versed in Chinese iconography! However, in the Cleveland Museum of Art online catalogue, this famille verte rouleau vase with finely executed important historical scene is described simply as ‘Vase with Decoration of Figures in Chariots’, which is tantamount to label Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) Last Supper ‘Painting of a Dinner Party at a Long Table’.

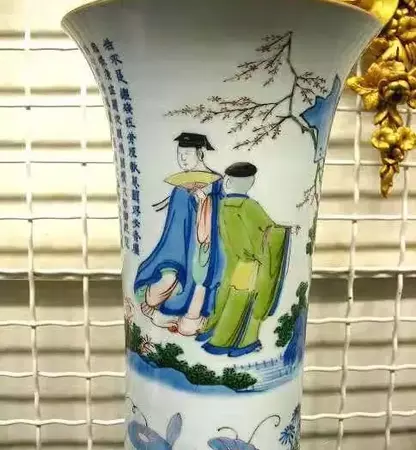

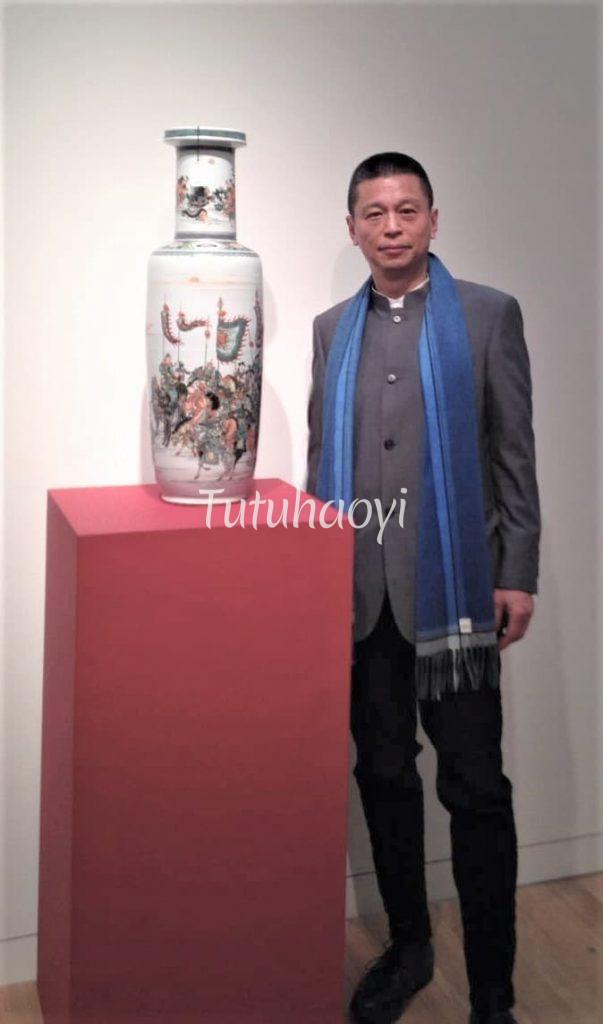

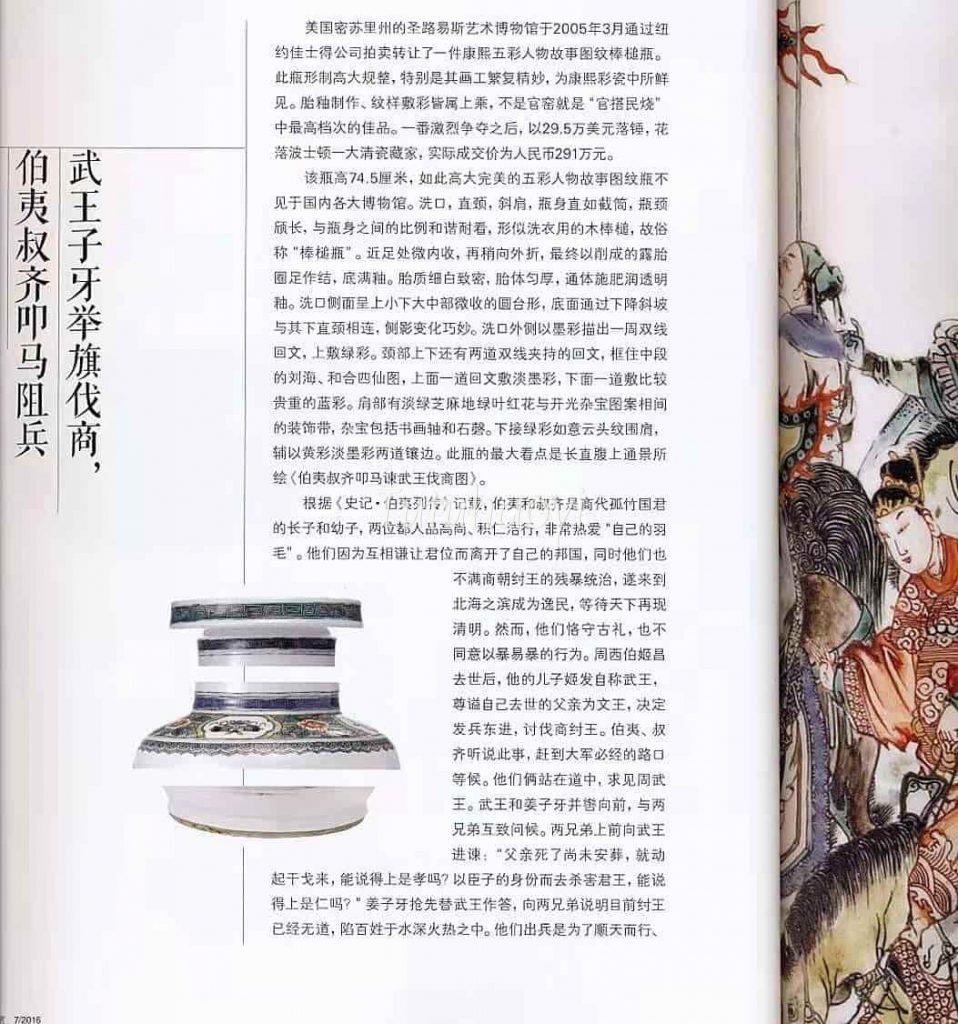

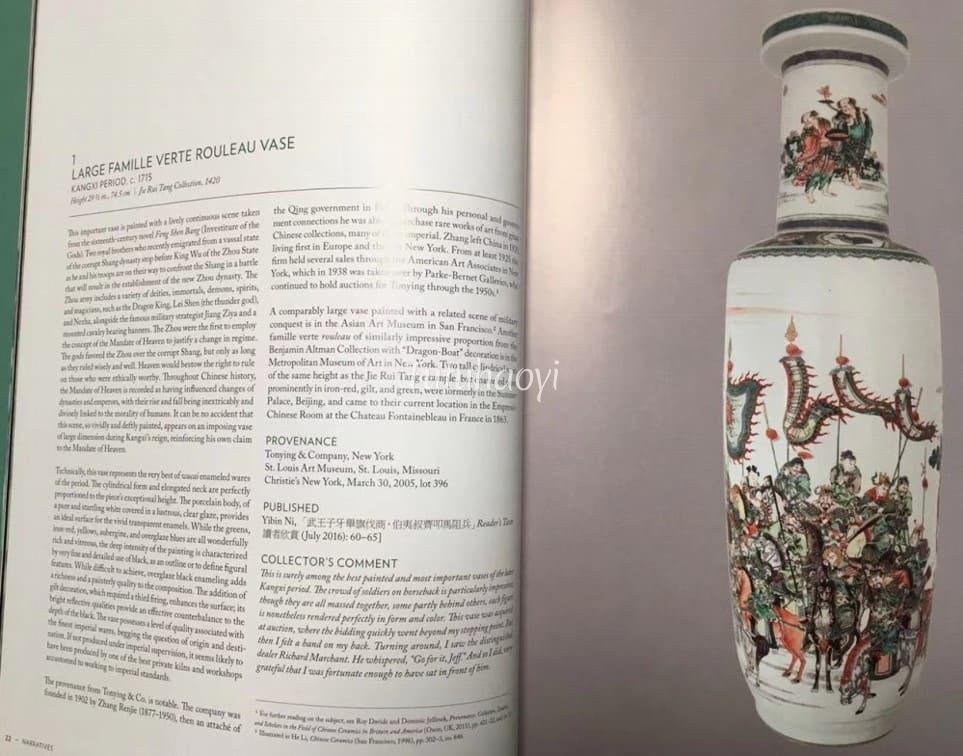

I first unveiled this story scene on a magnificent famille verte rouleau vase (see below) and published a series of scholarly articles to illuminate the historical significance and artistic value of the vase and the painting on it in 2005, 2008, and 2016, in both Chinese and English, such as《武王子牙举旗伐商, 伯夷叔齐叩马阻兵》in a Chinese journal Reader’s Taste (《读者欣赏》) in July 20161, and later in the book ‘A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection’. My lecture at Sotheby’s New York in 2018 has also put an emphasis on this vase, which certainly drew well-deserved attention to it during the auction.

This magnificent history theme, superbly represented by the former Jie Rui Tang vase, depicts a major dynastic transition in early China and the event depicted harbingers the longest-lasting dynasty, stretching for 790 years, in Chinese history. The complexity of its composition, the distinctive variety of the characters involved, and its strong and effective dramatic impact make it a rare treasure, comparable to Rembrandt’s ‘The Night Watch’, in the Chinese artistic tradition.

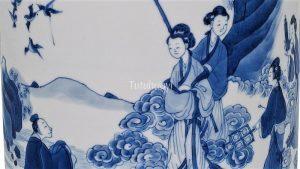

There are very few porcelain vessels in the world that depict such historical theme. Comparing the scene on the Cleveland vase with the above three classical examples of the same theme, we may be able to offer a few observations that are not only relevant to the more accurate dating of porcelain vessels, but also to picture production and dissemination and the ideological consideration behind the changes in the pictures.

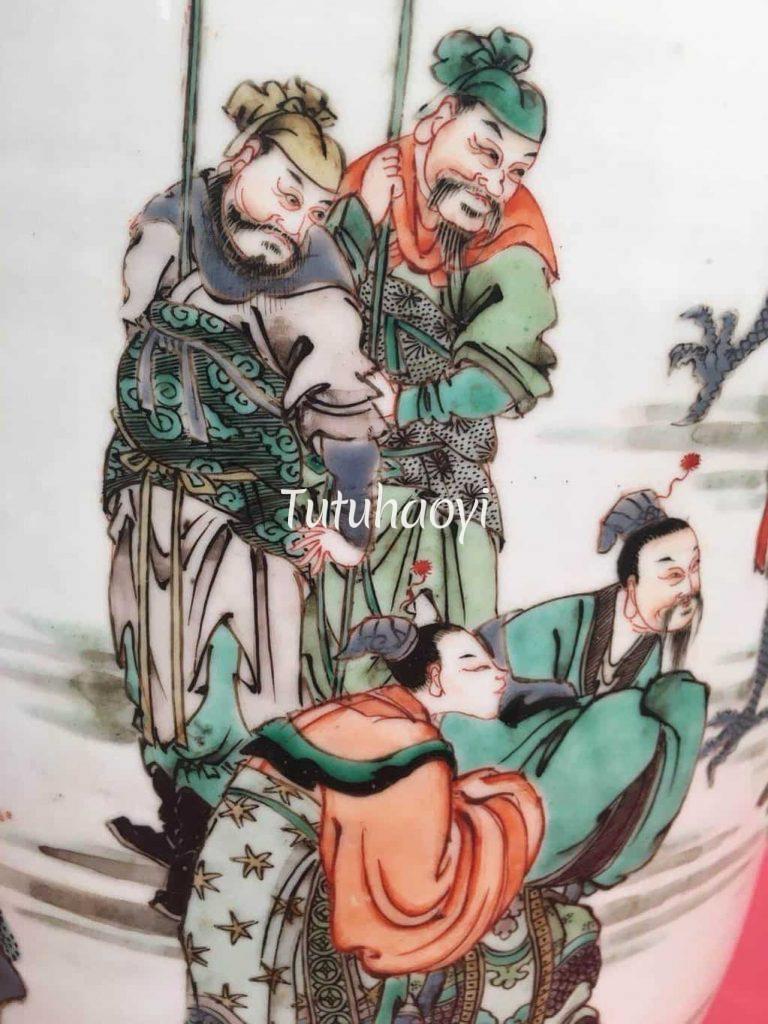

Compositionally, in the classical mode of this theme, Bo Yi and Shu Qi brothers are situated away from the approaching Zhou army, most prominently on the blue and white jar of the Chongzhen period (1628-44), to effect a tension between the two confronting parties. By contrast, on the Cleveland vase, the two brothers almost collapse onto the chariot of King Wu of Zhou and the two formerly separated groups have merged into one. As a result, the tension that exists between the two former parties has lost its formal base. The change of the relationship between different protagonists means a departure from the old tradition, which often implies a lapse in time. Therefore, it may well indicate that the Cleveland vase was probably painted in a much later date, as opposed to what the museum itself has dated.

Both on the Ming Chongzhen (1628-44) jar and Qing Shunzhi (1644-61) gu vase, Bo Yi and Shu Qi are characterised as commoners in cotton clothes with a bun as the headdress. They are kneeling before the Zhou Army. This copying of characterisation clearly shows the continuation of tradition between masters and apprentices within one generation even if the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) was replaced by the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and the transition brought brutal and drastic social changes.

However, on the Jie Rui Tang Kangxi (1662-1722) vase, the attire of Bo Yi and Shu Qi has been conspicuously upgraded to archaic embroidered silk gowns with decorative sashes. They also wear sophisticated headgear such as a jade or gold crown with a hairpin and a fluffy red ornament on the head. The two brothers are still positioned opposite the Zhou army bending over to show their modesty in front of King Wu.

Notably, the design of the same theme on the Cleveland vase represents a marked departure from the previous versions. Not only do the two brothers wear plain Ming-style official robes, but their heads are also covered with the official hats with two wing-like flaps that are popular in late imperial China. Such clear adoption of the later style of costumes again suggests the late execution date of the porcelain vase.

Literature:

1 Yibin Ni, 《武王子牙举旗伐商, 伯夷叔齐叩马阻兵》Reader’s Taste 读者欣赏 (July 2016): 60-65

2 Jeffrey P. Stamen and Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni (2017), A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection 文采卓然:潔蕊堂藏康熙盛世瓷, Jieruitang Publishing.

The findings and opinions in this research article have been written by Dr Yibin Ni.