Editor: Congratulations on art historian Dr Yibin Ni’s new research into a rare story scene in Chinese pictorial art, which may have puzzled contemporary museum curators and porcelain collectors. Dr Ni has traced the art historical context in which this rare pictorial scene of The Wife of the Bow Maker in the State of Jin was created and provided us with historical evidence to identify and illuminate its unique composition. His work on this previously mysterious story scene has undoubtedly contributed to the treasure trove of Chinese iconography.

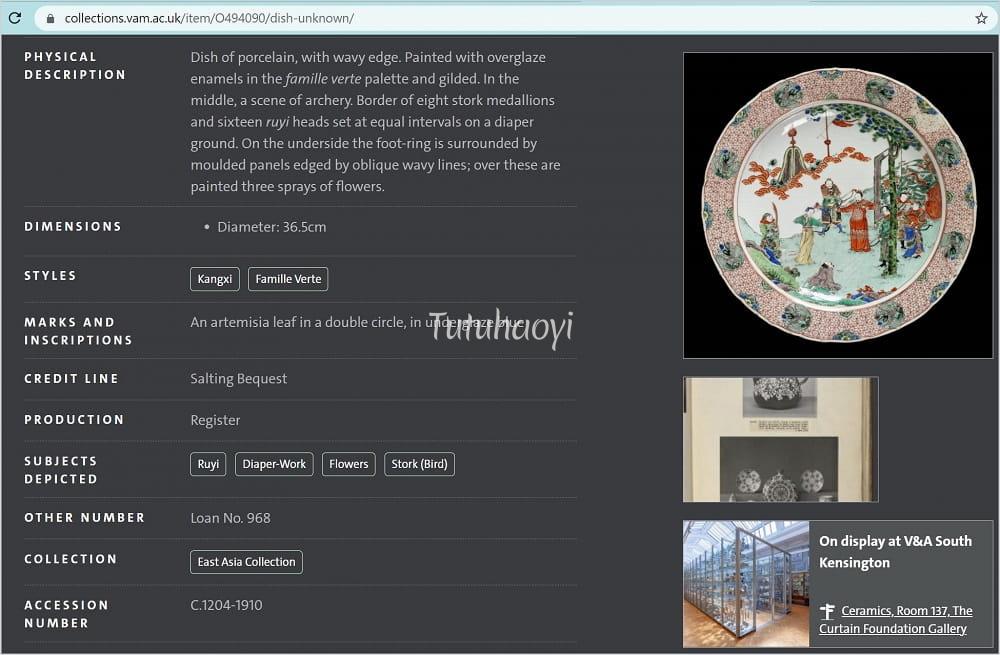

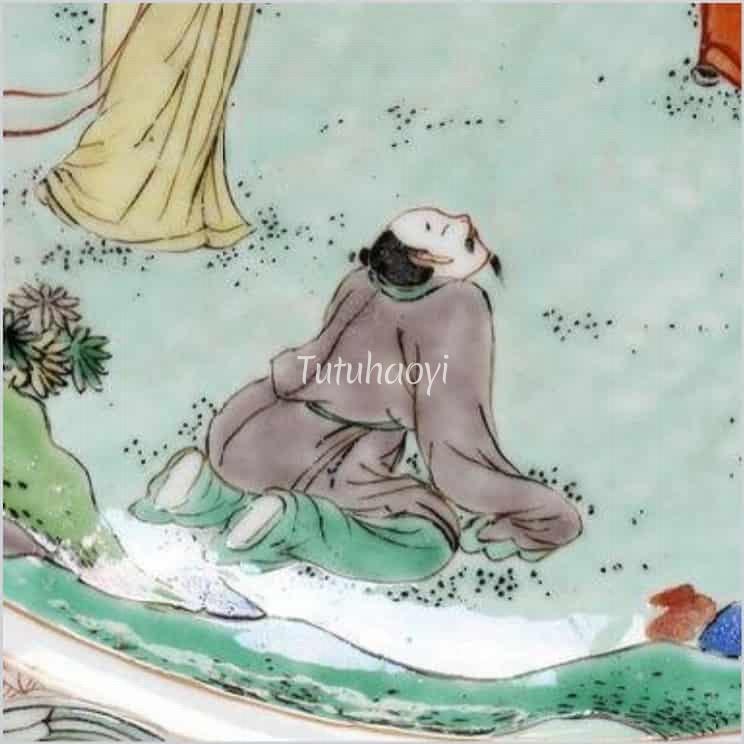

featured image above: porcelain dish with overglaze enamelled decoration, Kangxi period (1662-1722), courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London

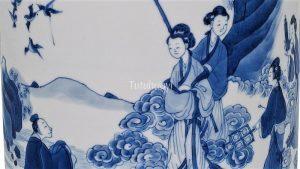

screenshot from V&A Museum https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O494090/dish-unknown/, accessed on 16 Aug 2021In the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, there is a large famille verte dish and the online catalogue describes the narrative painting in the middle with only four words: ‘a scene of archery’. In the scene, there is a group of military personnel carrying bows surrounding a dignitary wearing a red robe and a gold crown. They are looking at a woman pulling the string of a bow. In the foreground, a kneeling middle-aged man faces the dignitary. On the right, stands a three-fold screen with a ferocious red dragon rising from a choppy sea. In front of the screen, there is a chair covered with expensive red brocade. Obviously, there is a dramatic tension among these people and it is more than a mere ‘scene of archery’.

As a matter of fact, the scene represents a fascinating story of a brave woman who boldly exercised her rhetorical competence, managed to correct the erring ruler and saved her husband from execution. The story is entitled ‘The Wife of the Bow Maker of Jin (晋弓工妻)’, recorded in Chapter 6 Convincing and Perceptive (辩通传), Biographies of Exemplary Women (列女传 Lienv zhuan), the earliest extant book for moral education of women in China.

Duke Ping of Jin (晋平公, r. 557-532 BCE) was the sovereign of the State of Jin. Once he ordered a bow to be made for his personal use and the job took three years to finish. The duke happily received the new bow and tried it out with great expectation. Wooden strips for writing at that time were used as the testing target. The duke was sorely dismayed when the arrow did not pierce even one layer of the wooden strips. The duke wanted to have the bow maker executed for his utter incompetence. As soon as the bow maker’s wife heard about the news, she rushed to the palace. In front of the duke, the bow maker’s wife demonstrated her brilliant mastery of reasoning skills. First, she quoted famous benevolent anecdotes practised by past admirable rulers. Second, she enumerated all the best materials her husband had managed to select over a very long time in order to make this finest bow. Third, she pointed out that it is absolutely absurd to blame the bow for the previous ineffective shooting since it was none other than the result of the duke’s misuse of the bow. She then went on teaching the duke the right way of holding the bow and drawing the string and the right moment to release the arrow. The duke followed her advice. This time, the arrow hit the target and went right through seven layers of wooden strips! The reputation of the bow maker was instantly restored and the duke rewarded him 60 taels of gold.

The devil is in the details. The V&A dish is a remarkable example of depicting a complex story in a single format. Once the viewer knows the story, all the key elements in it can be found in the painting: the wronged bow maker, the demonstrating wife, and the bow testing field.

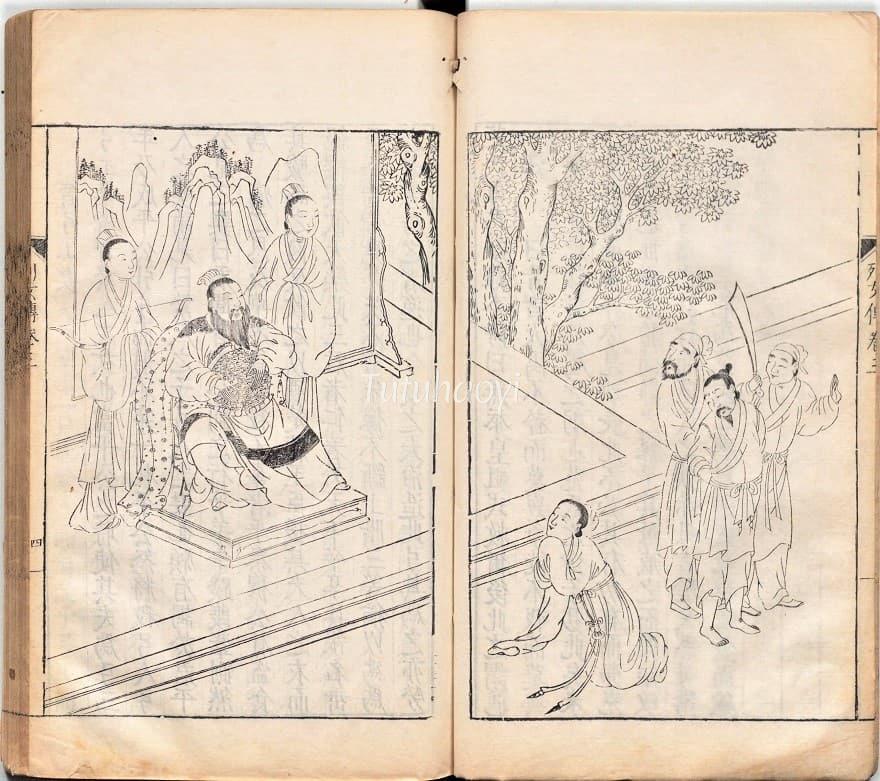

By contrast, the three major existing illustrations of the same story in three different versions of the woodblock printed book Biographies of Exemplary Women are all less illuminating. The earliest one shows a passive and summary scene: the duke is holding the bow after his lousy shooting, the bow maker is being taken away by a jailer, and the bow maker’s wife is standing aside, looking miserable. Obviously, the picture does not convey the gist of the story.

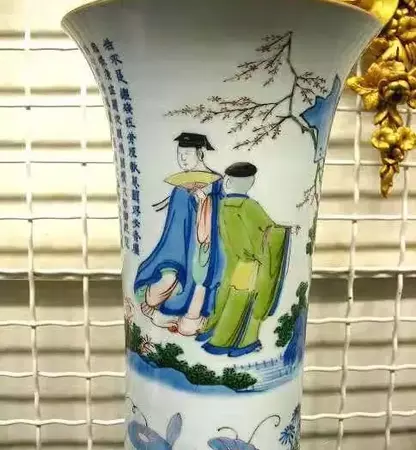

In a very sophisticated illustration of the same story, probably designed by the well-known Ming professional painter Qiu Ying (仇英 d. 1552), the three main protagonists are all present. The bow maker is about to be taken away for execution. His wife is kneeling in front of the duke, speaking out in a distraught manner. The duke is sitting on a platform and one of his courtiers behind him is holding the bow in question. Compared with the confident woman skillfully demonstrating the art of archery in the porcelain painting, the characterisation of the wife in this illustration renders her as a mere pitiful crying lady.

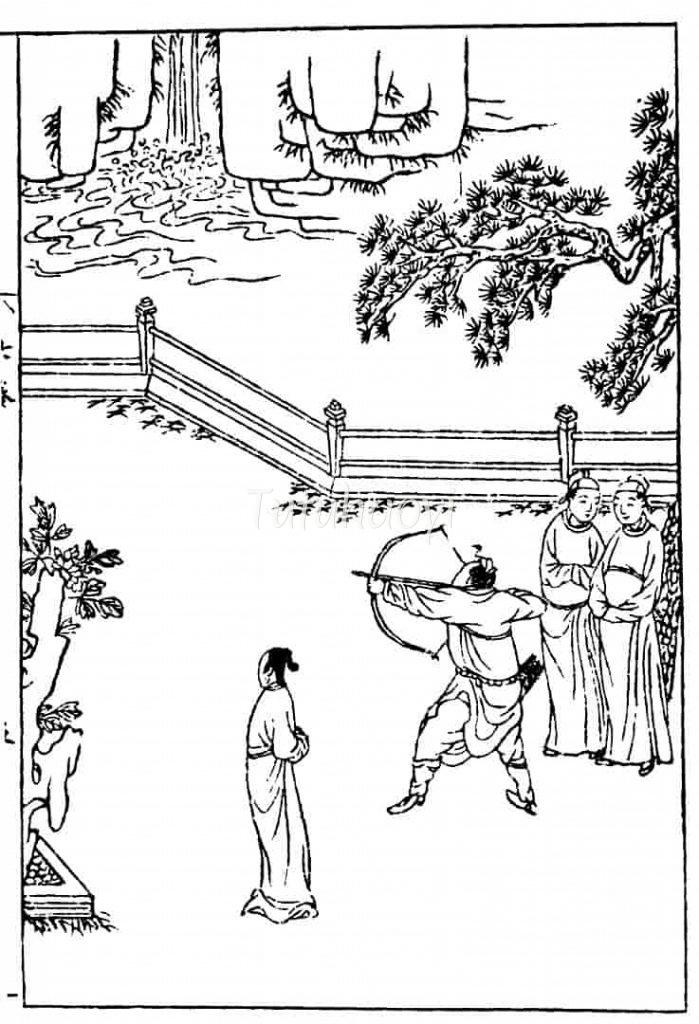

The third illustration presents an idyllic archery scene with a man ready to shoot and a woman and some assistants looking on. Without being told by the caption of this picture in a book of Biographies of Exemplary Women, one can hardly sense that it is about an able wife who saved her husband in front of a duke.

There are very few images on this topic extant in China, and we are pleased to find that Chen Guchang (陈谷长, born 1942), one of the contemporary Chinese artists, did an exquisite water colour painting of the bow maker’s wife and achieved a desirable result in an auction in 1984.