Editor: The following blog is modified from Dr Yibin Ni’s research work first published on Antiques and Fine Art Magazine in 2002. The purpose is to appreciate how Chinese porcelain painters from ancient times passed on classical stories and illustrated traditional morals through their craftworks.

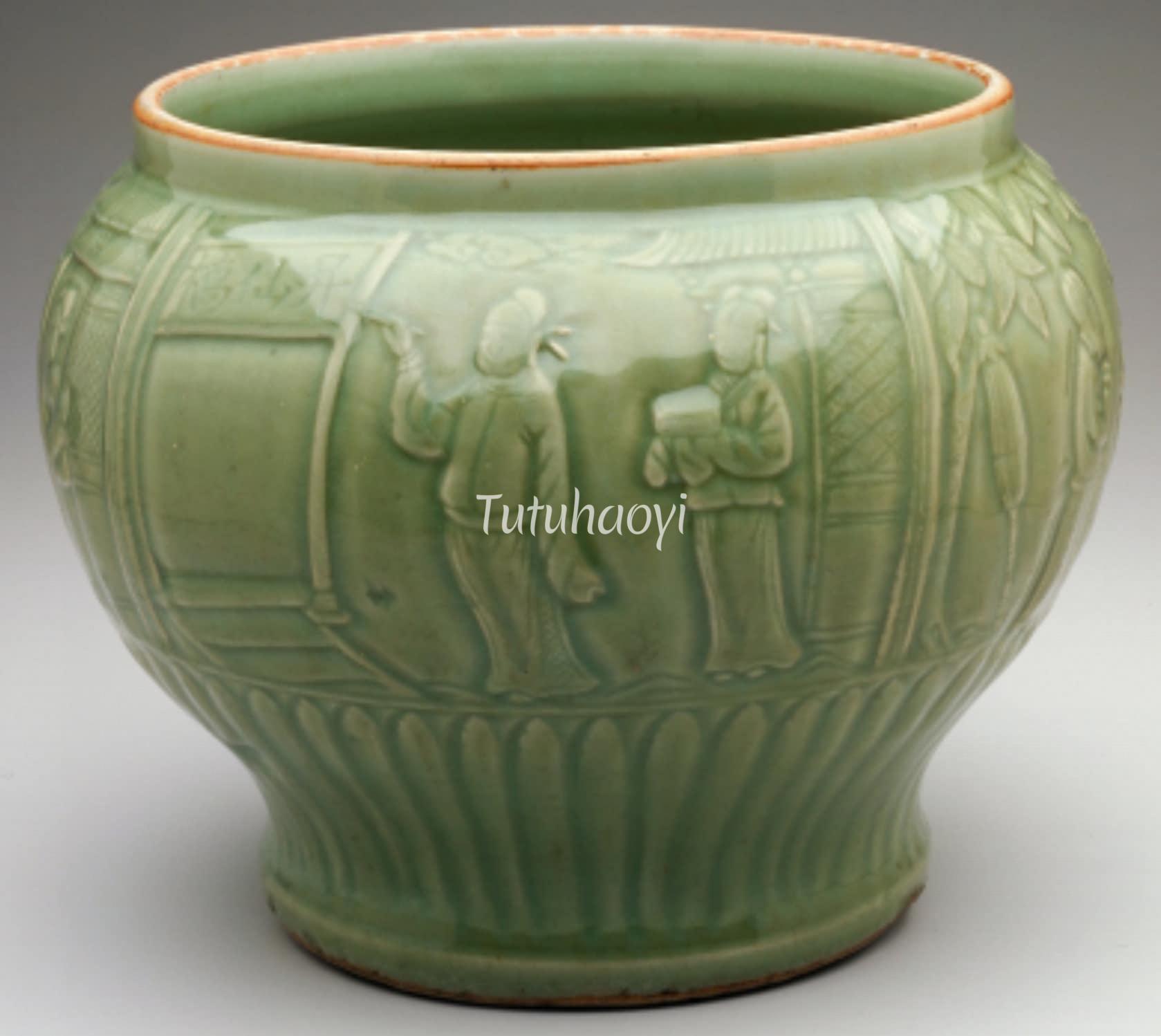

featured image: celadon jar (detail), 14th century, courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

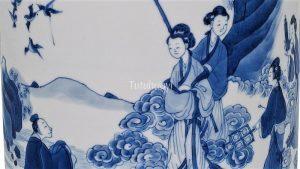

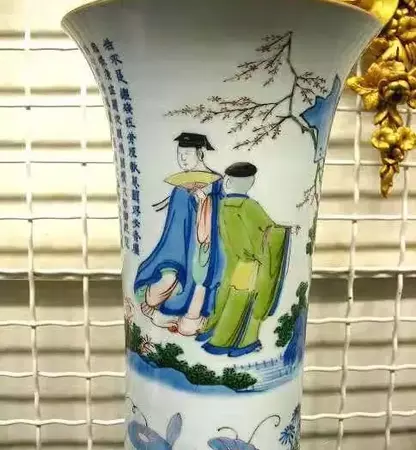

A scene of the poet Sima Xiangru (179-117 BC) of the Western Han dynasty inscribing his ambition on a bridge pillar (司马相如题柱, also called 相如题桥) is depicted on a magnificent trumpet-mouthed vase potted around the mid-seventeenth century. The anecdote was first recorded in a fourth-century gazetteer and later widely recounted in many primers from the Tang (618-907) to the Ming (1368-1644) dynasties. As a grain in the Chinese literary tradition, it has inspired generations of readers by demonstrating how ambition and hard work could result in great success.

The story relates that when Sima Xiangru was a poor young scholar he was able to demonstrate his musical talent one day by playing the qin zither at a party given by a rich businessman. There, he won the heart of the rich man’s recently widowed daughter, Wenjun (文君), with whom he eloped during the night. Humiliated, Wenjun’s father refused to support the couple, and the poverty-stricken pair had to earn their living running a wine shop by the roadside. One autumn day, encouraged by his beloved wife, Sima Xiangru made up his mind to seek his fortune in the capital, Chang’an (present-day Xi’an). He parted from Wenjun on the bridge leading to the city, and there, vowed that he would not cross the bridge again unless he did so riding in a carriage drawn by four horses; meaning he would only return home accompanied by fame and fortune. In the capital, Sima Xiangru impressed the emperor with his talents and made a successful career in court. He was then sent back home by Emperor Wu (reigned 140–86 BC) as an envoy to the barbarians in western China. Arriving in his horse-drawn carriage, he was received by the local officials with the highest of honours.

The exquisitely executed painting on the vase shows Wenjun holding the ink stone for Xiangru while he writes his vow on one of the pillars on the bridge. Though the porcelain painter did not know the techniques of chiaroscuro, he delineated Xiangru’s robe with highly fluid lines, which are highlighted with lighter washes to create the contours of a wind-blown garment. Projecting over a strategically positioned rock are gnarled tree trunks with distinctively angular branches, reminiscent of the Song (960-1279) academician tradition. Further, imitating the painting format then in vogue that combined painting with poetry and calligraphy, a short poem is inscribed next to the rock:

Had Xiangru not had the ambition he wrote on a pillar by the bridge, then how could he expect to return riding high up in a four-horse-drawn carriage? (相如不奋题桥志 安得高乘驷马车)

This is a truly remarkable tableau in the best tradition of Chinese figural painting.

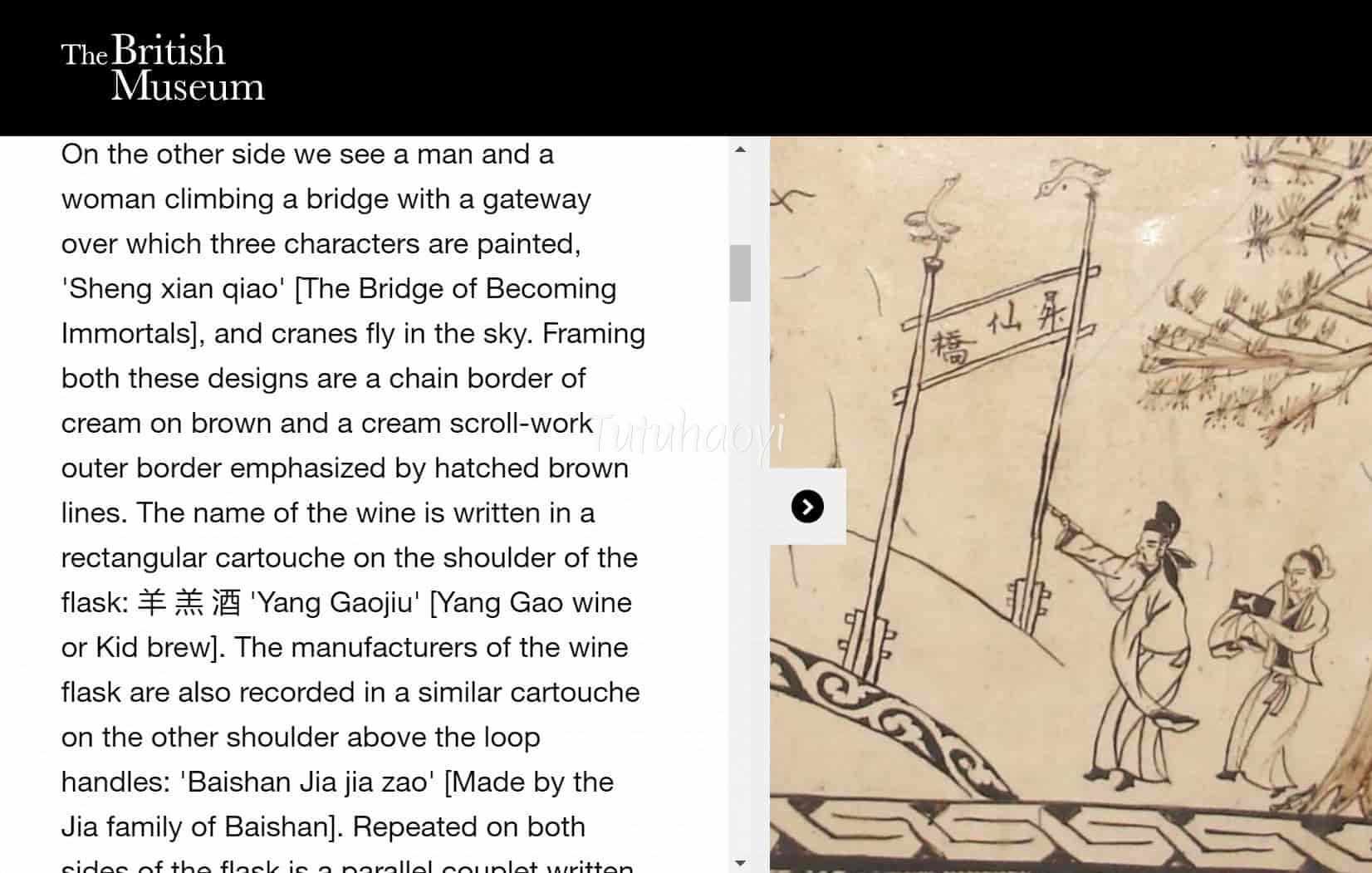

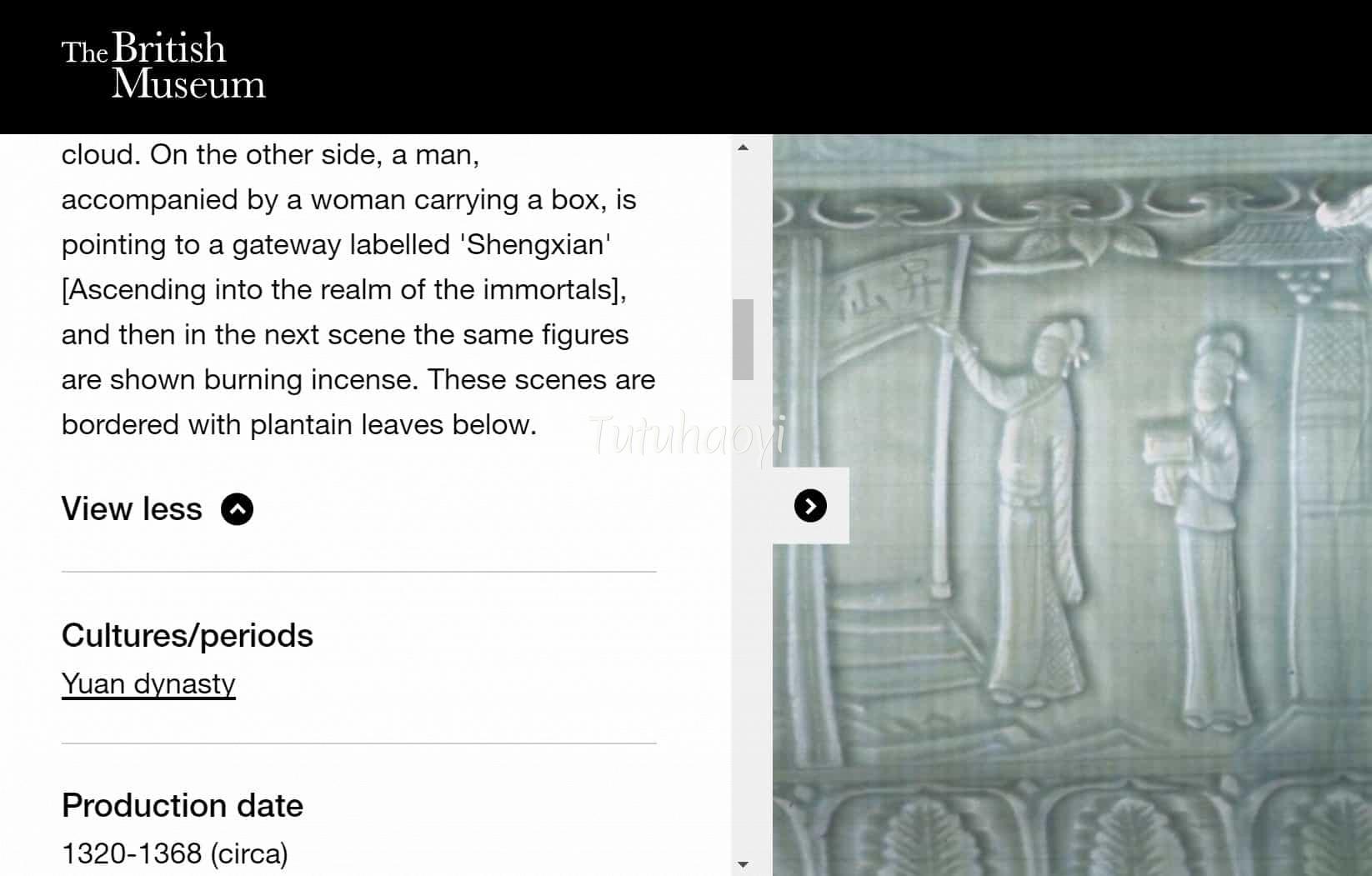

Before my identification of this scene at the turn of the new millennium, in scholarly works such as ‘Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum’ by Jessica Harrison-Hall (2001, published by The British Museum Press), the scene was described as ‘… a man and a woman climbing a bridge with a gateway over which three characters are painted, Sheng xian qiao [The Bridge of Becoming Immortals], …’(p. 435), and ‘a man, accompanied by a woman carrying a box, is pointing to a gateway labelled Shengxian [Ascending into the realm of the immortals], …’ (p. 468). Rich content and a moral message conveyed by ancient painters are thus lost by such plain description of the image.

Minneapolis Institute of Art so far has left no description of the image for its 14th century celadon jar.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.