Editor: Today is the Chinese Duanwu or the Double Fifth Festival. On this day, Chinese people have a variety of practices, such as drinking rice wine sprayed with realgar powder, hanging images of the Heavenly Master on the lintel, and displaying the Five Poisons on clothes, utensils, and toys. But where did this tradition come from and how were these practices depicted on various artefacts over the last one and half millennium? We have invited renowned art historian Dr Yibin Ni to explain this through his comprehensive research work.

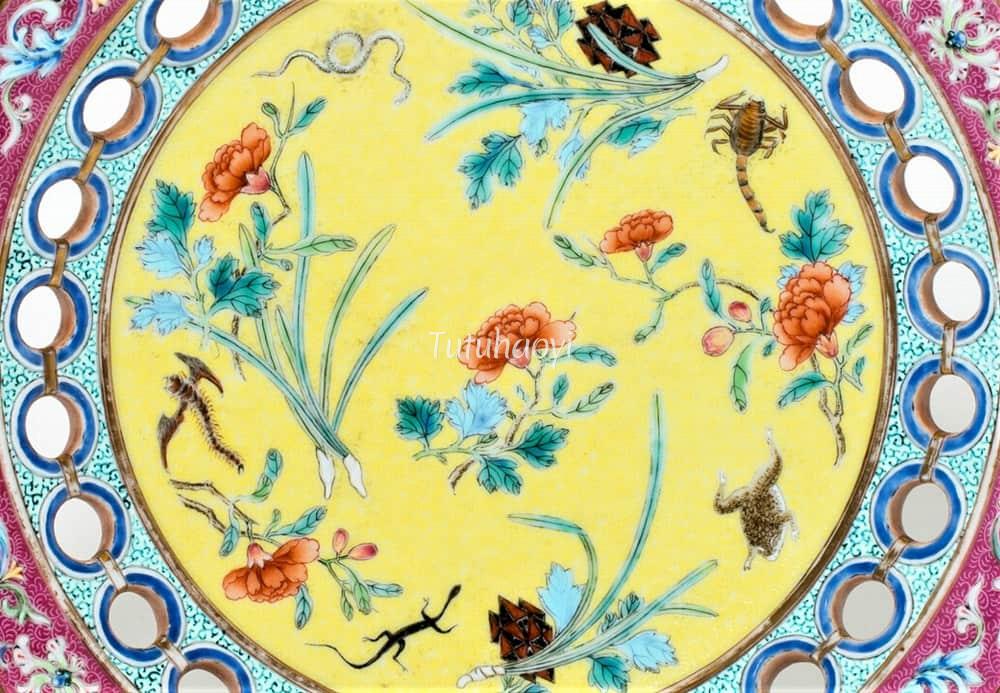

featured image above: porcelain dish (detail) with overglaze enamel decoration, Qianlong period (1736-95), courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Duanwu (端午 duānwǔ) is the festival celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar. Its date varies from year to year on the Gregorian calendar. Summer solstice, the longest day in the year, occurs in the fifth month of the Chinese calendar and Chinese astronomy believes that it stands for the apogee of the yang force in the annual cycle. The sun, like the Chinese dragon (龙 long), symbolises masculine energy in the universe. Ancient philosophers warned in Classic of Changes (易经 Yi Jing) that ‘When the sun has reached the meridian height, it begins to decline (日中则昃)’ [Commentary on the fifty-fifth hexagram 丰 Feng]. The Book of Rites (礼记 Liji), one of the core texts of the traditional Confucian canon, has a section entitled ‘Proceedings of Government in the Different Months (月令)’. It considers the fifth month as ‘one during which the yin and yang forces struggle and the tendencies to death and life become apparent (阴阳争﹐死生分).’ In a word, the ancients believe that the day the yang force arrives at the highest point is the day we have to be on alert because it means in the present cycle the yang force is destined to diminish. It evolved into the folklore belief that the fifth month is an inauspicious one (‘五月俗称恶月’), as per Festivals and Seasonal Customs of the Jing-Chu Region (荆楚岁时记 Jingchu Suishiji).

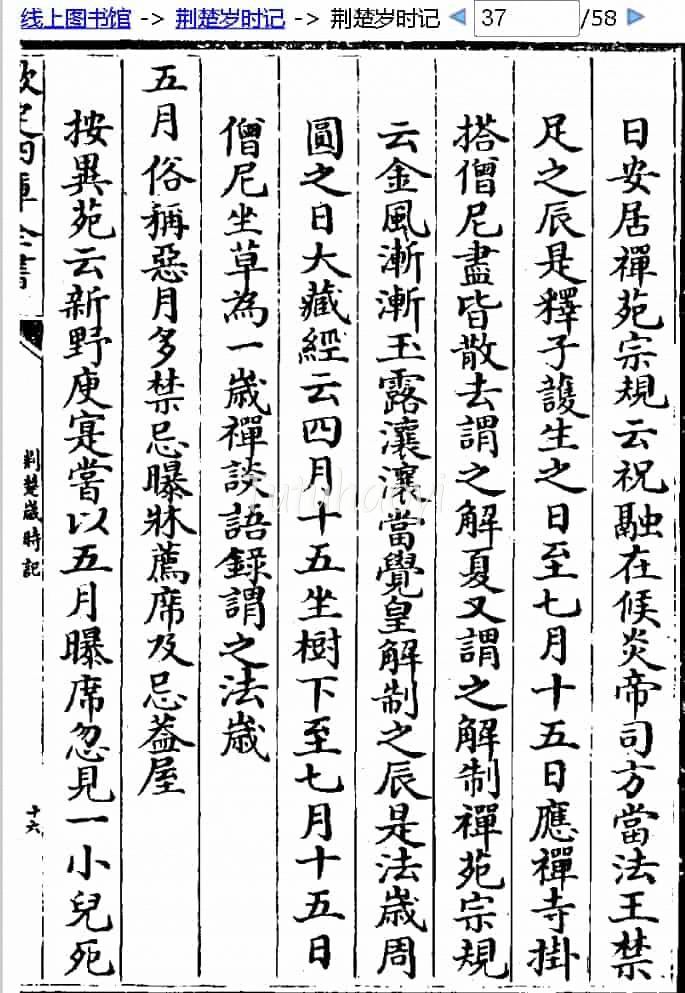

During the Warring States period (战国, 475BCE- 225BCE), a nobleman’s son was born on the fifth day of the fifth month. The father strongly believed the superstition that children born in the fifth month would be natural enemies of their parents and gave the order that he should be done away with (‘初,田婴有子四十馀人。其贱妾有子名文,文以五月五日生。婴告其母曰: ‘勿举也’) [Biographies of Lord Mengchang, Records of the Grand Historian 史记 • 孟尝君列传]. The fifth day of the fifth month came to be regarded as one of the most dangerous days of the year when evil spirits and hazardous creatures lurked around. Notably, five noxious creatures were identified, known as ‘Five Poisons (五毒 wǔ dú)’. Initially, they are the centipede, the lizard, the scorpion, the snake, and the toad.

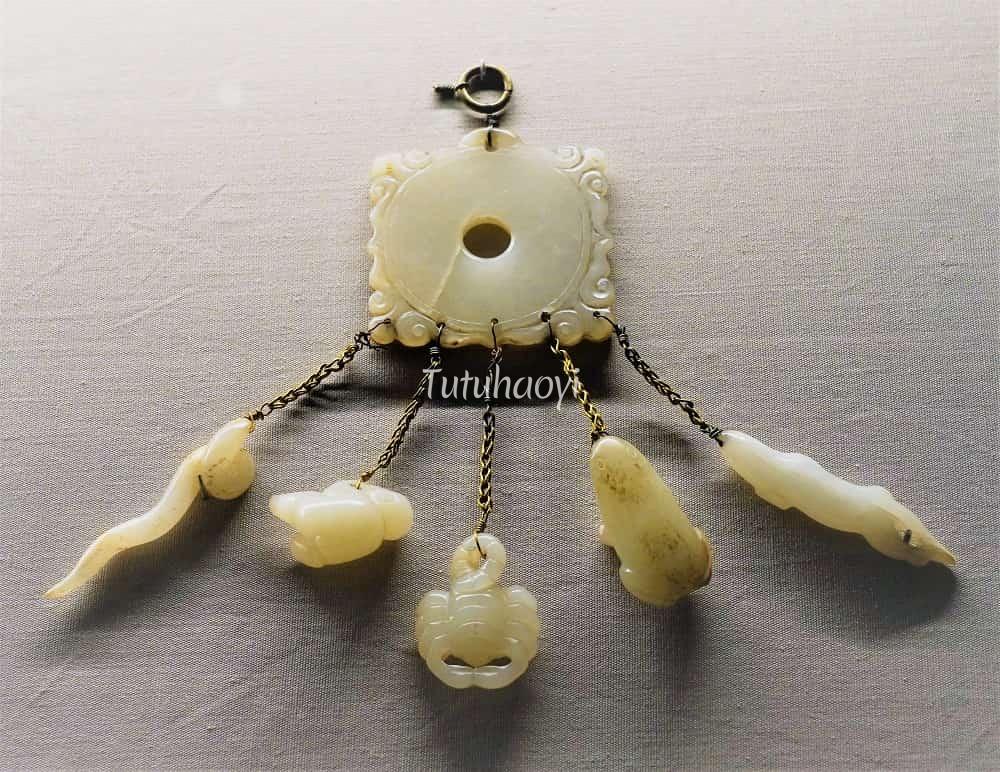

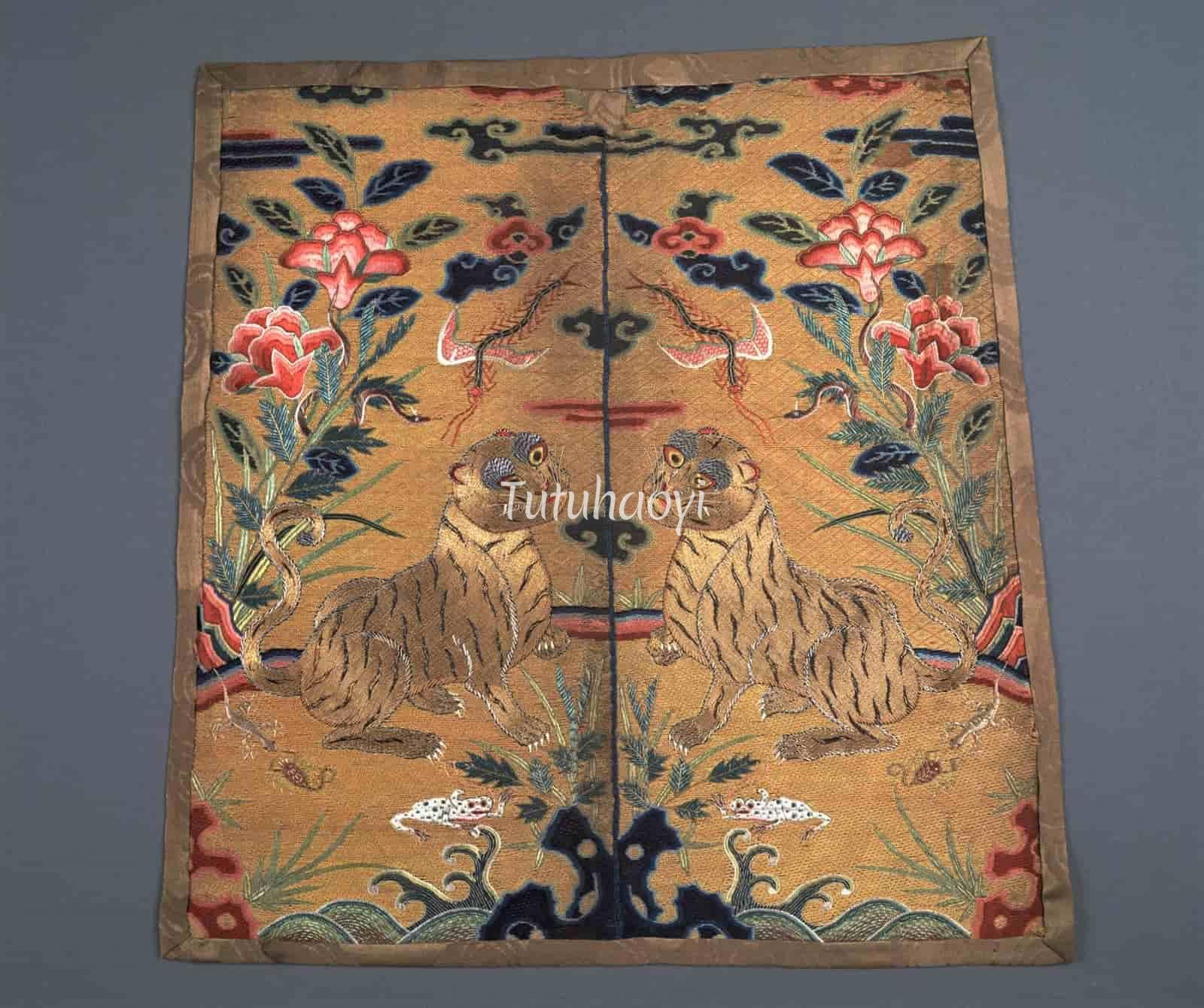

In order to deal with the hazards and quell the evil spirits, the Chinese use the strategy of ‘combating poison with poison’. Adults would drink rice wine sprayed with realgar powder (雄黄酒) which contains potent arsenic sulfide. Children would wear small pouches filled with strong-smelling mugwort and amulets with images of the ‘Five Poisons’ on them. On children’s face or sometimes even their chest, realgar slurry would be smeared in the shapes of some talismanic characters or the character ‘王’ (wang). The 王 character represents the tiger, king of the animal realm. Such a 王 character can be found on the head of the tiger on the Ming gold ornament in Suzhou Museum. Clothes and mandarin squares adorned with the ‘Five Poisons’ would be worn by the fashion-conscious members of the society during this festival.

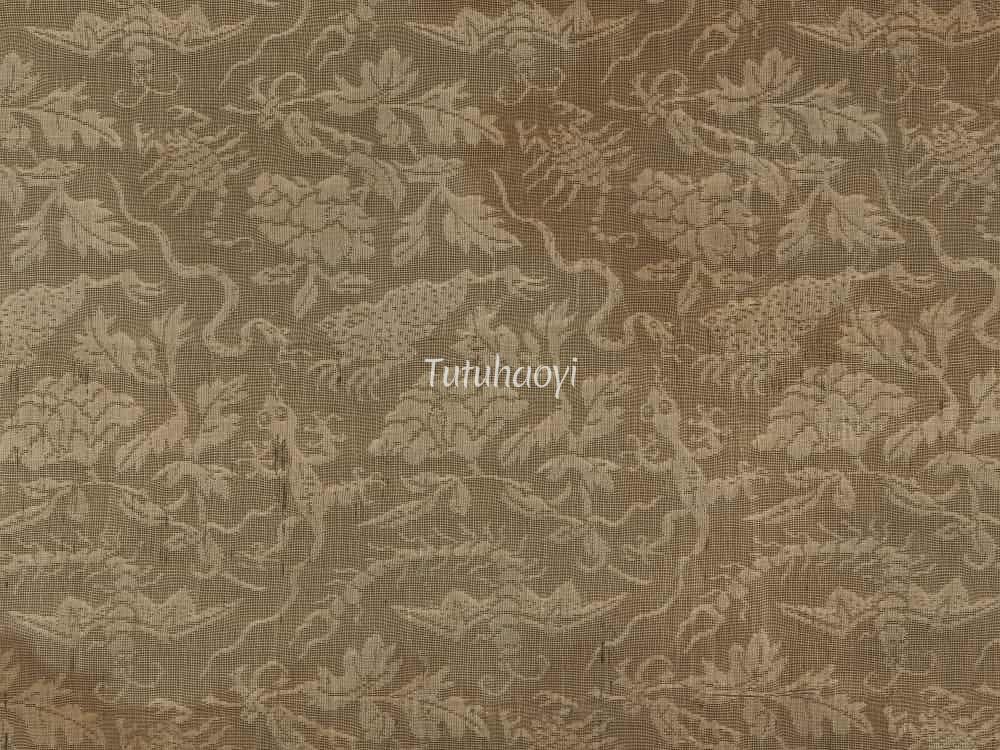

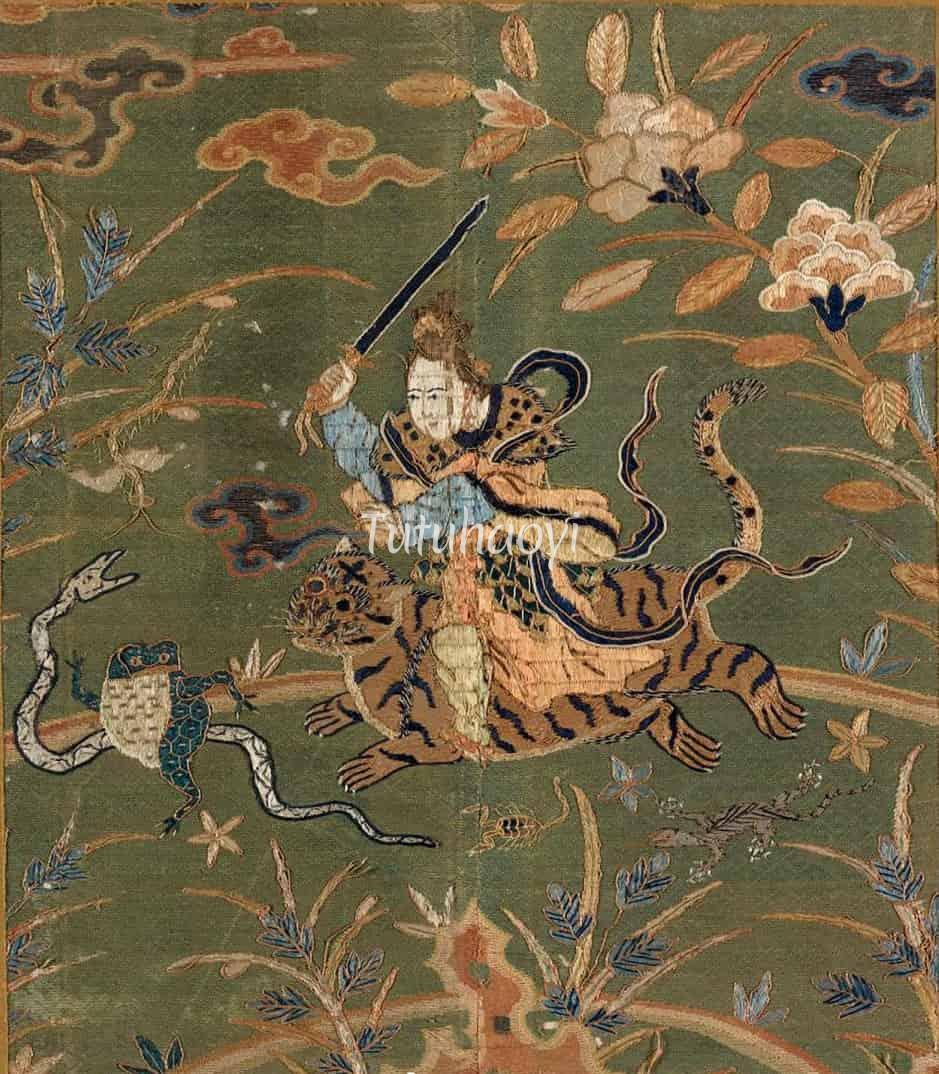

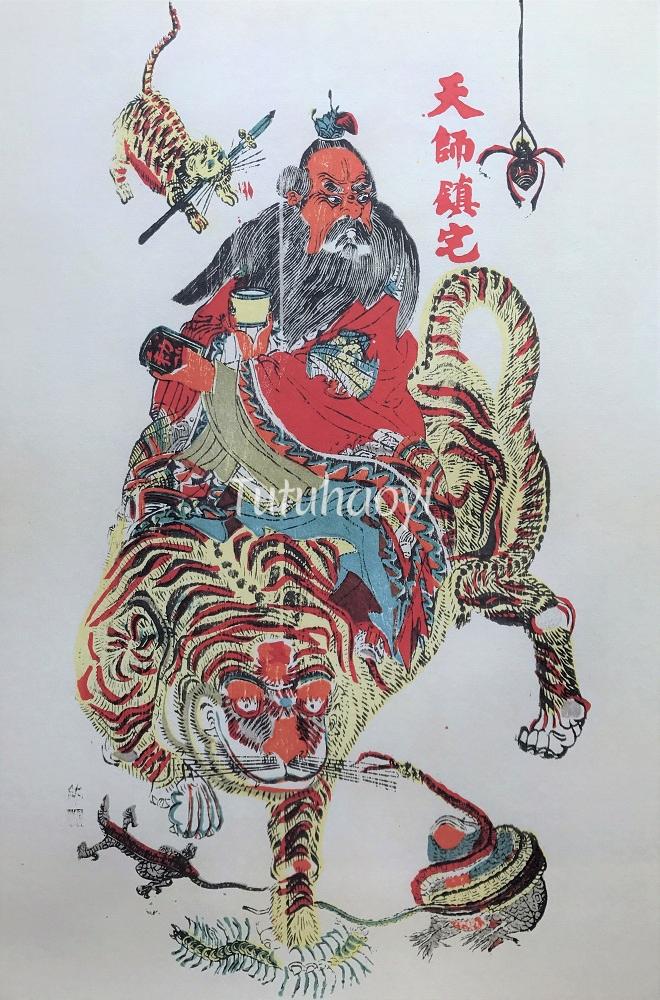

Gradually, the exorcising power was personified as a ‘heavenly master’, often riding a tiger. A Dream of Sorghum (梦梁录 Mengliang Lu), an account of the daily-life in the capital Lin’an (臨安, modern-day Hangzhou 杭州) during the Southern Song dynasty (南宋, 1127-1279) is one of the earliest sources to mention the ‘Heavenly Master Zhang (张天师)’ as a Duanwu festival decoration. An effigy of him made from calamus or the rice-paper plant would be hung on the lintel, sometimes together with heads of the tiger and other auspicious beasts, to protect the household.

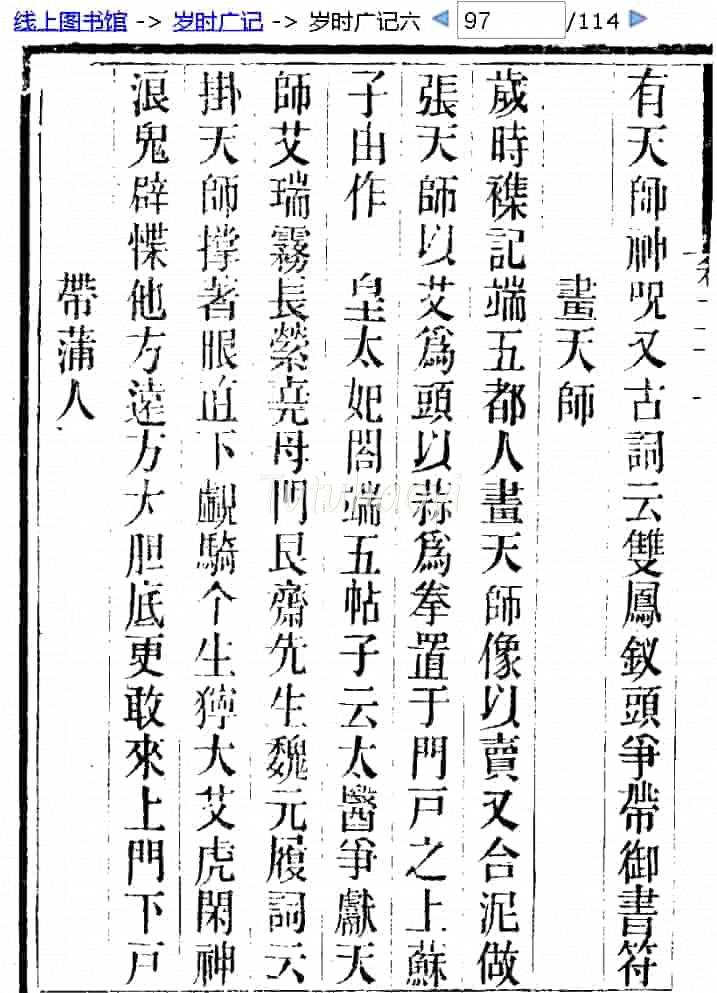

Extended Report on Festivals of a Year (岁时广记 Suishi Guangji), compiled by Chen Yuanjing (陳元靓 ca. 1200-1266) has a section entitled ‘Portraying Heavenly Master’. It says that during the festival, the Heavenly Master’s portraits were painted and on sale and a version of its effigy had its head formulated by mugwort and fists modified from garlic bulbs (‘画天师像以卖。又合泥做张天师,以艾为头,以蒜为拳’). It also quotes contemporary song lyrics describing the Heavenly Master ‘riding a giant fierce mugwort tiger’. These botanical dummies are perishable and we could only guess what they looked like.

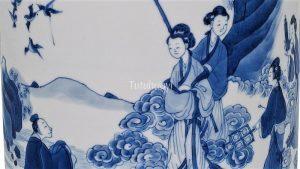

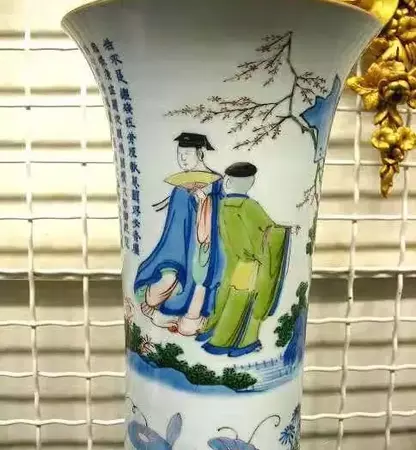

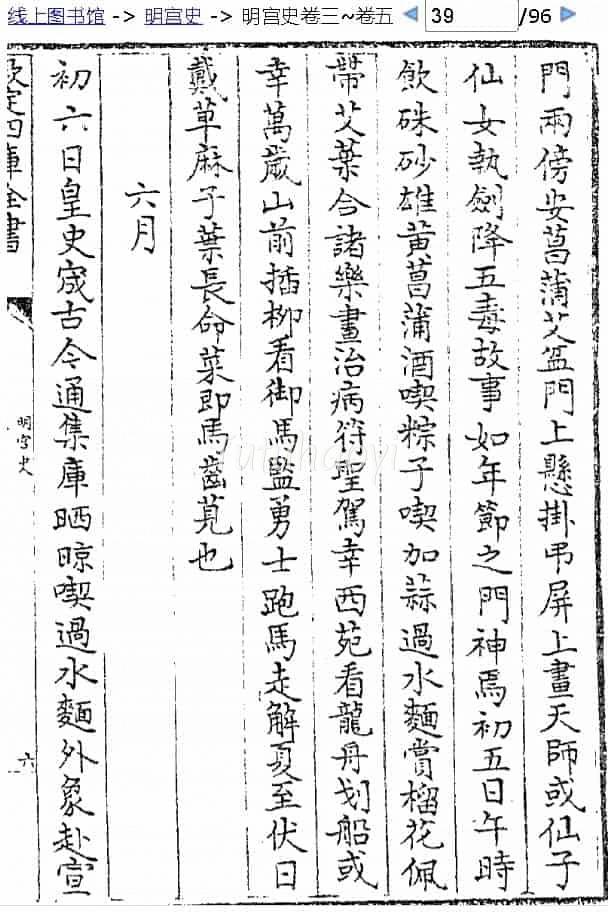

History of the Ming Court (明宫史 Ming Gongshi), a Ming-dynasty book mentions that pictures of the Heavenly Master, or a young deity, or a fairy subduing the Five Poisons with a sword would be framed and hung on the lintel for a whole month, just like the door gods during the Chinese New Year (‘门上悬挂吊屏,上画天师或仙子、仙女执剑降五毒故事’). Such images are now still available on porcelain, metal ornaments, and embroidered fabric.

Sure enough, some of these images portray a young male deity, a sword in his right hand and a cup of sacred water in his left hand and the character fits the written description of a ‘young male deity (仙子)’. One may misidentify the scene if one only tries to look for an elderly-looking Heavenly Master, as is the case in the May-June issue of the Arts of Asia magazine, 2010, in which a Wanli-period (万历, 1572-1620) bowl with this scene is said to have ‘a Scene of Li Ji Slaying a Snake’.

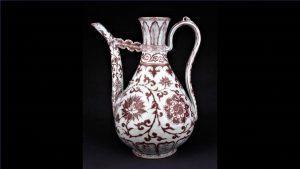

An example of a female protagonist can be found on a Ming-dynasty embroidered fabric piece, on which a fair in fancy garments brandishing a sword and charging at a snake, a toad, and a centipede on a tiger. On a pair of Ming-dynasty gold hairpins, a boyish-looking deity is manoeuvring with the Five Poisons on the back of a ferocious tiger. There are two modes on a group of dishes with underglaze blue and overglaze enamel decoration fired during the Wanli period. The male deity either rides a tiger disguised as a qilin or walks among the Five Poisons, waving his sword at them.

Extant images of eminent-looking Heavenly Master Zhang with a full beard riding a tiger in his battle with the Five Poisons are rare and they tend to be not earlier than the 19th century.

The findings and opinions in this research article have been written by Dr Yibin Ni.