Editor: In Chinese culture, the Mid-Autumn Moon Festival is related to the legendary fairy Chang’e, the Moon Goddess. We often see a hare, her loyal companion, and an osmanthus tree in the picture with her against a background of the Moon Palace. However, why does Chang’e often hold an osmanthus sprig, and what does this deity have to do with scholars attending civil-service examinations? Let’s invite Dr Yibin Ni to explain to you with his interesting literary research findings.

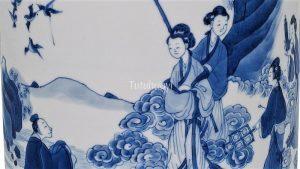

featured image above: porcelain jar (detail), Shunzhi period (1644-1661), dated 1646, with later painted decoration, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

The Mid-Autumn Moon Festival falls on the night of full moon in the eighth lunar month. Chang’e (嫦娥) the Moon Goddess, is usually associated with this family-union occasion, together with the festival food – the moon cake (月饼). A legend recorded in an ancient Chinese book, The Huainanzi (淮南子 The Discourses of the Huainan Masters), compiled around 139 BCE, says that a beautiful girl called Chang’e has been living on the moon for thousands of years. Chang’e’s husband was the legendary archer, Hou Yi (后羿 houyi), and he was given the elixir of immortality by the Queen Mother of the West (西王母 Xiwangmu) for his merits. Out of boredom and curiosity, Chang’e tasted the elixir. As a result, she turned into an immortal. Her body became so light that she ascended to heaven, ending up in the nearest planet, the moon. On the moon, there was a huge osmanthus tree, a toad, and a hare grinding the tree bark with a pestle in a mortar to prepare some magic medicine. The adorable hare became Chang’e’s loyal companion.

The osmanthus tree prominent in the Moon Palace or chan gong (蟾宫), the Toad Palace, came to be a symbol for elite talents during the Jin (晋) dynasty (265-420). When the Emperor Wu of Jin (晋武帝, 236-290) asked Xi Shen (郤诜, act. 265-74), a man of letters, to do a self-evaluation, Xi Shen claimed that he was the most talented and most able man in court, like a sprig of blossom in the osmanthus woods (犹桂林之一枝) and a piece of jade in the Mount Kunlun. Later, the Tang poet Li Duan (李端, 743-82) used ‘a fish having jumped over the Dragon Gate and a sprig of osmanthus blossom having been plucked (登龙兼折桂)’ as metaphors to refer to his friend’s recent success in passing civil-service examinations with flying colours in his congratulatory poem.

Since there was a famous osmanthus tree in the Moon Palace and Chang’e was the perfectly presentable permanent resident there, she gradually evolved into the role of the osmanthus sprig giver. Just like the Greek goddess Nike who rewarded winning warriors with a wreath of laurel leaves, Chang’e with a sprig of osmanthus flowers in her hands symbolised academic success in imperial China. Thus, art works bearing images of Chang’e bestowing a sprig of osmanthus blossom to scholars have become suitable presents for those who sit for examinations ever since.

A Jiajing (1522-66) blue-and-white bowl of the Ming dynasty in the collection of Zhenjiang Museum, Jiangsu Province, China, may have been one of the earliest examples of this auspicious scene for examination sitters. Chang’e’s Moon Palace is indicated with a disc under an osmanthus tree. It encircles a sliding door, some floor tiles, and a corner of a standing screen with a plaque on top bearing two characters ‘蝉宫 (chan gong)’ meaning ‘Moon Palace’. In addition to the inscription and the osmanthus tree, another key attribute of Chang’e is the hare reserved in white against a cobalt blue background nearby. In front of these characteristic pictorial elements stands Chang’e with a tall hairdo and silk sashes fluttering around her on a cloud. A maid with a feather fan on a pole in the vicinity shows Chang’e’s prestigious status. Next to her comes a successful scholar clutching an osmanthus sprig in his right fist.

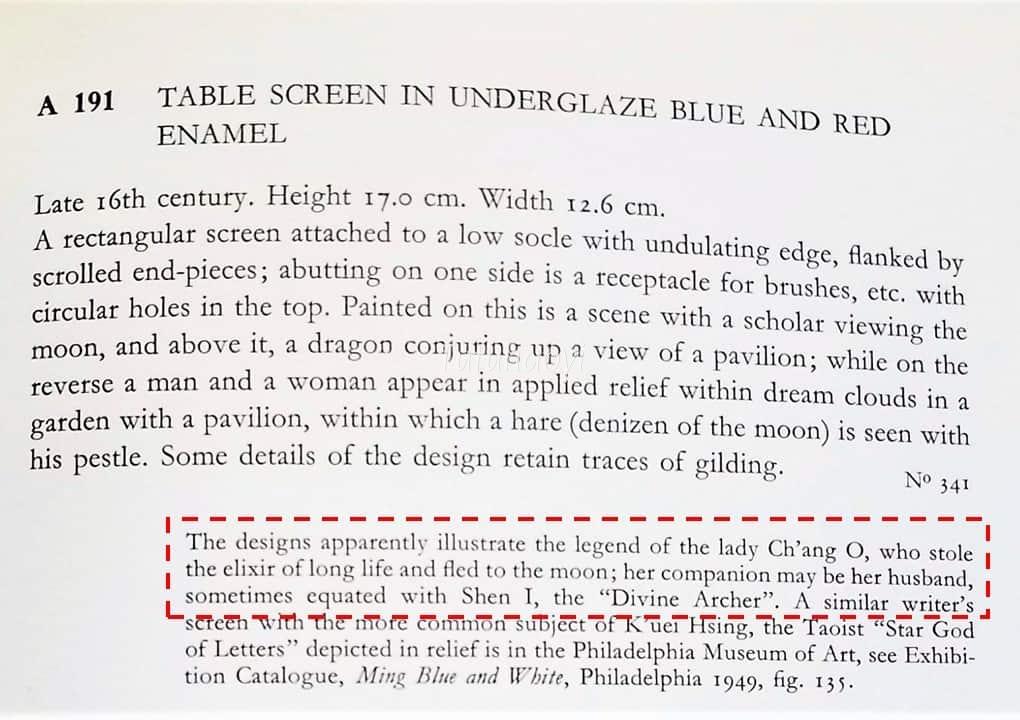

On the two late 16th or early 17th century objects bearing this scene, the lucky single recipient of the sprig stands on the left and Chang’e is on the right, which seems to have set a norm for most of the following examples. Chang’e occupies a higher position to indicate that she is either in the heaven or descends from it. On the adorable table screen in The Baur Foundation, Geneva, Chang’e’s Moon Palace is indicated by a corner of a two-tiered rooftop, a blossoming osmanthus tree, and a hare pounding elixir in a mortar with a pestle in the doorway. On the other hand, the officially-attired scholar is happily riding on a cloud gesticulating to the lady. Without knowing this allusive connection, even an expert may misinterpret the identities of the figures in the scene. The Baur Collection’s official catalogue correctly identified Chang’e but mistook the blessed scholar as her husband! Obviously, the owner of this table-screen-cum-brush-pen-holder would have brimmed with hope and confidence to achieve good academic results.

By contrast, on a Ming ink cake in the collection of Palace Museum, Beijing, it is Chang’e and her maid who are arriving on a cloud with a fluttering tail in the sky, symbolically shadowed by branches of an osmanthus tree. This time, the successful scholar is miraculously standing on a sea of clouds, holding the rewarded osmanthus sprig.

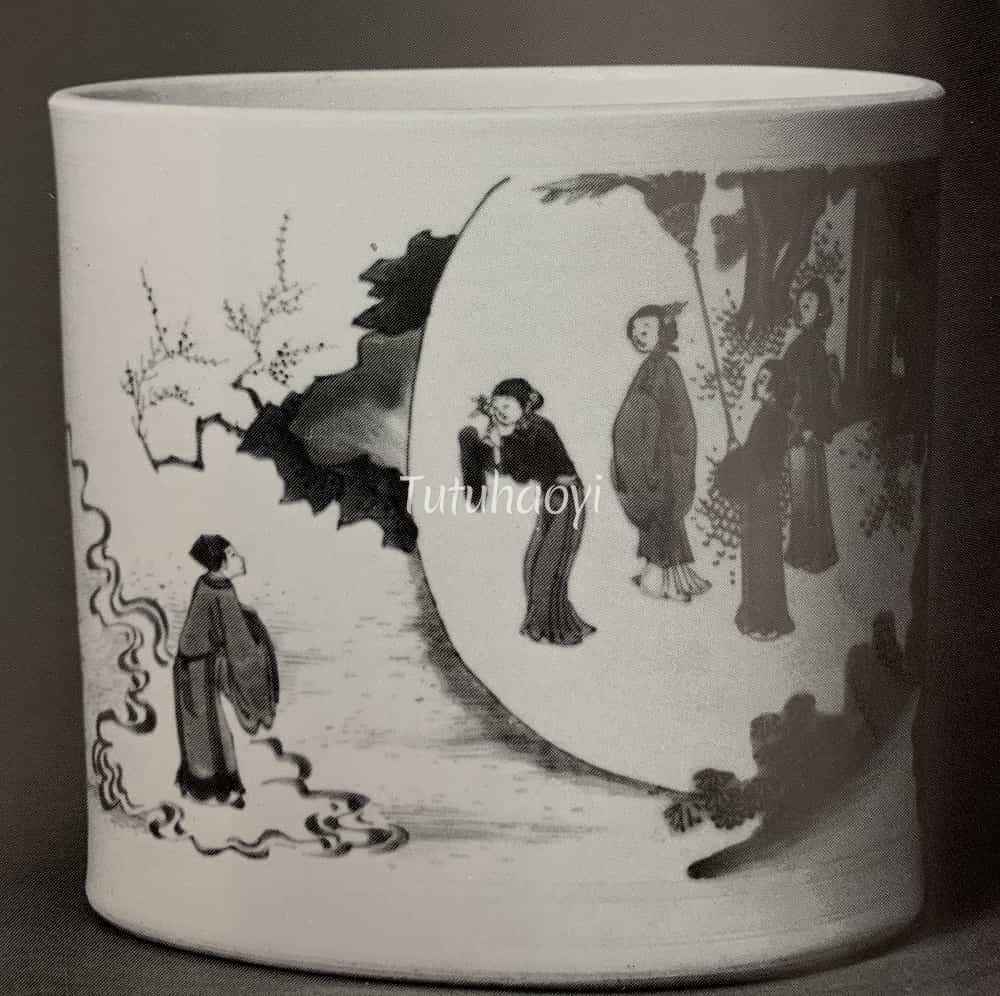

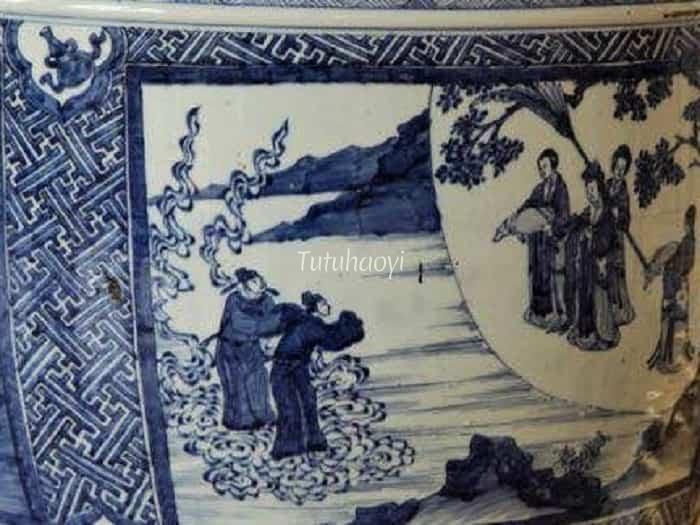

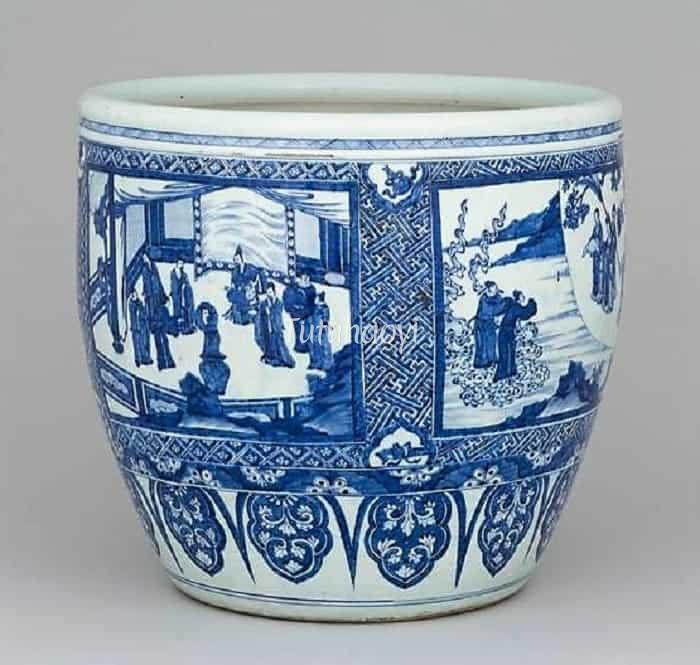

The surface of rounded porcelain pieces such as brush holders and rolwagens are usually treated as a handscroll on which a pictorial narrative can be spread out, conventionally from right to left. On a transitional blue-and-white brush holder, Chang’e’s dwelling is formally represented as a partially emerging moon, with a long contour curve separating her entourage from the scholar recipient. In front of the osmanthus tree and some architectural element, Lady Chang’e is canopied by a ceremonial feather fan and it is one of her maids who is offering a sprig to the scholar who belongs to the separated realm of mortals. Like in the version on the Baur screen, his vehicle to the Moon Palace is a cloud with a trailing tail. Without knowing the specific story, the writer of the catalogue can only conjure up a hypothesis that the scene is ‘a scholar gaz[ing] upon a beautiful lady who appears within a cartouche’.

porcelain brush holder with underglaze blue decoration, 2nd quarter of the 17th century (The present author has unfortunately misplaced the reference of this catalogue and the identification of the reference by our resourceful readers would be most appreciated.)

There are versions of this scene with more than one scholar on the receiving side and they may have been based on a scene in a play. They appeared as early as the Shunzhi period (1644-61) and the number of male recipients could be as many as four, as is the case of the Kangxi blue-and-white vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

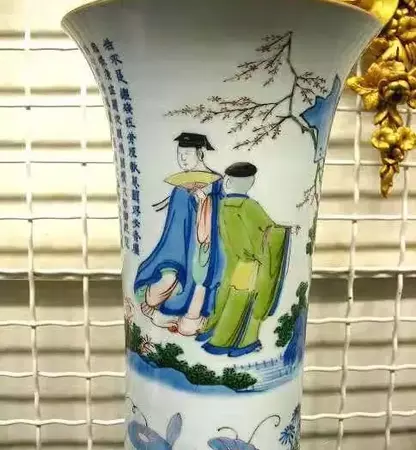

Some related scenes were derived from the ‘Chang’e-bestowing-the-sprig’ prototype and carried the same cultural significance as a good-wish token for examination sitters. For example, in the ground-breaking exhibition catalogue Transitional Wares and Their Forerunners there is a Chongzhen blue-and-white rolwagen that carries the image of a well-dressed lady about to decorate a scholar’s head with a sprig of osmanthus flowers. It is certainly not a man’s toilette scene but a well-wish for the beloved to pass the incoming civil-service examinations successfully.

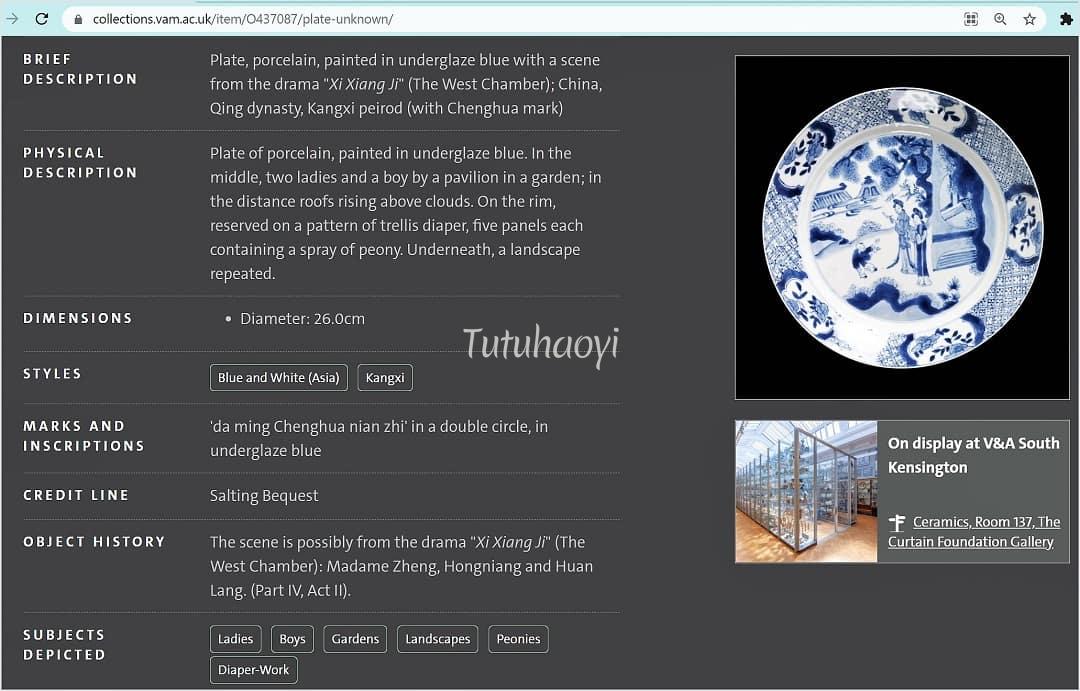

The online catalogue of Victoria and Albert Museum in London describes the scene on a Kangxi blue-and-white plate as ‘possibly from the drama “Xi Xiang Ji” (The West Chamber): Madame Zheng, Hongniang and Huan Lang. (Part IV, Act II)’. However, the lady with fluttering sashes in the middle surely is too young to be Madame Zheng, mother of the protagonist of the play Yingying. Furthermore, she is actually holding a sprig of osmanthus blossom to offer to the boy with extended hands. This is none other than another version of the pictorial allusion to zhe gui (折桂), i.e., ‘plucking a sprig of osmanthus blossom’.

An earlier version with the same intended meaning can be found on a Chongzhen blue-and-white rolwagen. A well-groomed lady with a fancy silk gown and a fashionable hairdo of the Late Ming is bestowing an osmanthus sprig to two enthusiastic boys, while the third boy is contented with a sprig in his hands.

porcelain rolwagen with underglaze blue decoration, Chongzhen period (1628-44), (The present author has unfortunately misplaced the reference of this catalogue and the identification of the reference by our resourceful readers would be most appreciated.)

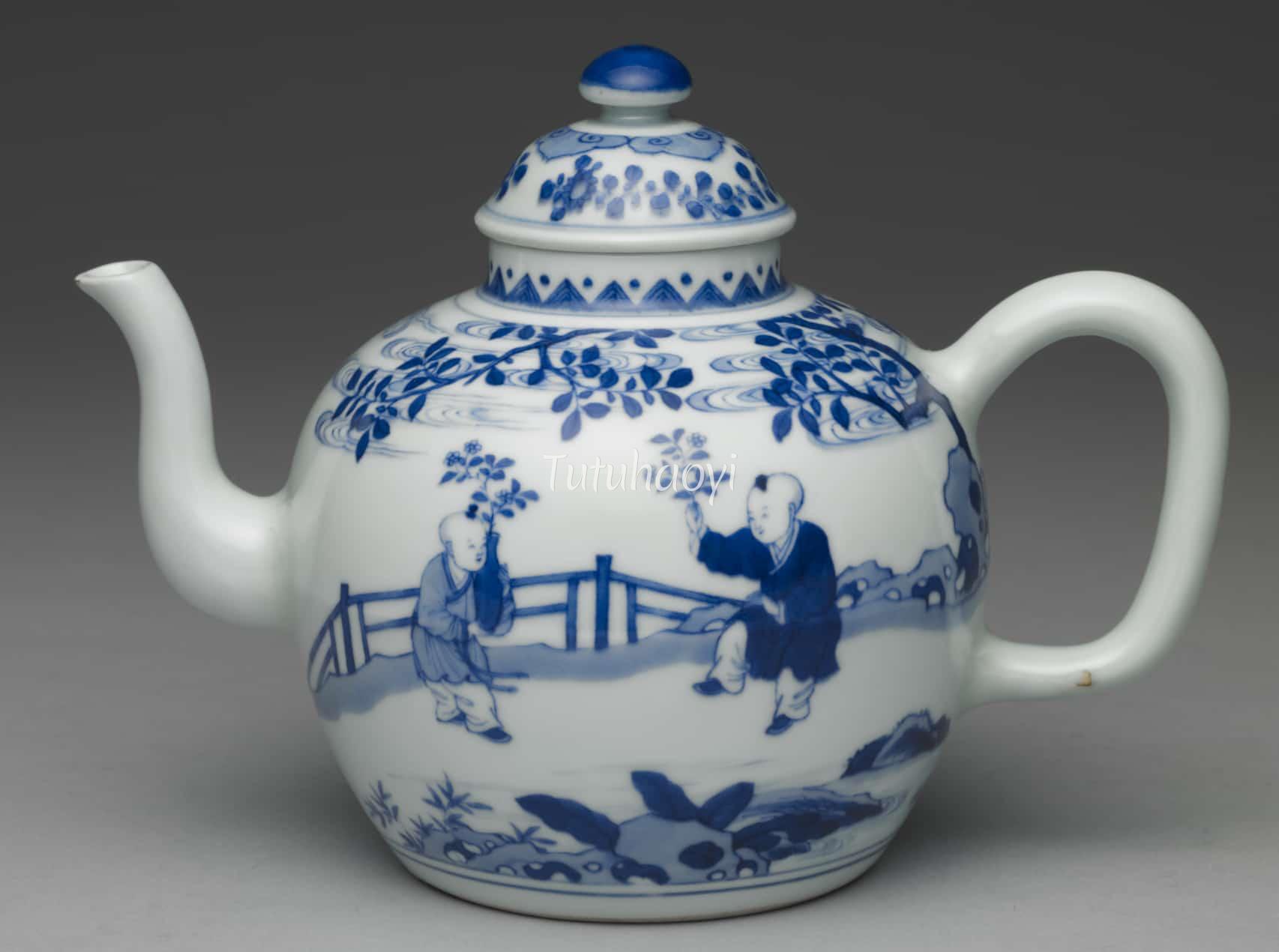

The same ‘osmanthus-sprig offering’ gesture in turn appears in another well-liked design called Ying Xi Tu (婴戏图), i.e., Children at Play, in which boys offering the sprig to their playmates. Sometimes, the porcelain painter rendered small characteristic osmanthus flowers into some larger generic flowers, as is the case on a Yongzheng blue-and-white tea pot in the National Place Museum, Taipei. But their intended meaning is still clear, especially in the specific context discussed in this article. The boys are not interested in flowers, but the symbol of a bright promising future.