Editor: Have you ever wondered why the image of the prunus has been a popular motif in Chinese decorative art? Why do Chinese literati love to write poems about plum blossoms and paint them in their art works? Dr Yibin Ni will explain to you the symbolic meanings of the prunus and how scholar-artists started to relate themselves to the prunus from the Song dynasty onward.

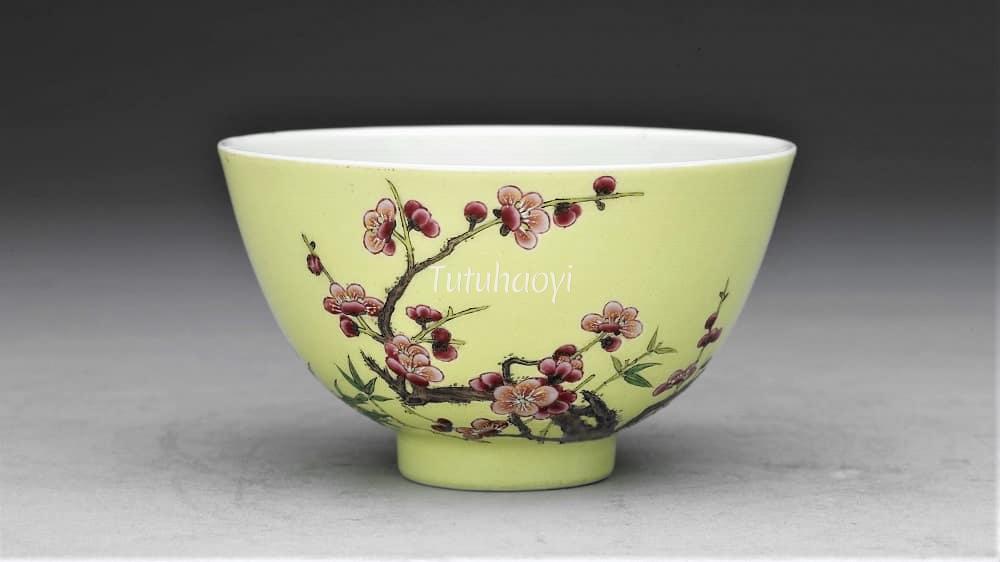

image above: falangcai porcelain tea cup, Yongzheng period (1723–35), Qing dynasty, courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

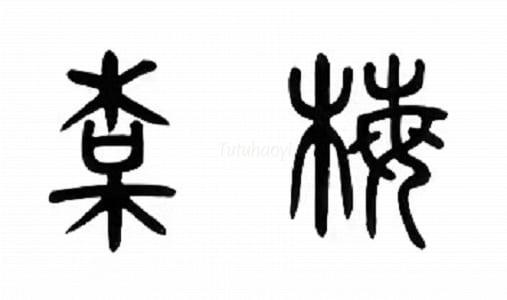

The tree commonly referred to in English as the flowering plum in fact belongs to the species Prunus mume, which is part of the apricot family. The epigraphic form of the character 梅mei for ‘prunus’ is an image of a large plum on top of a tree, with the radical for ‘tree’ above (see character on the left in the image below). In the extant seal script form of the character there is a sound element at the right-hand side that means ‘flourishing grass’ (see character on the right in the image below).

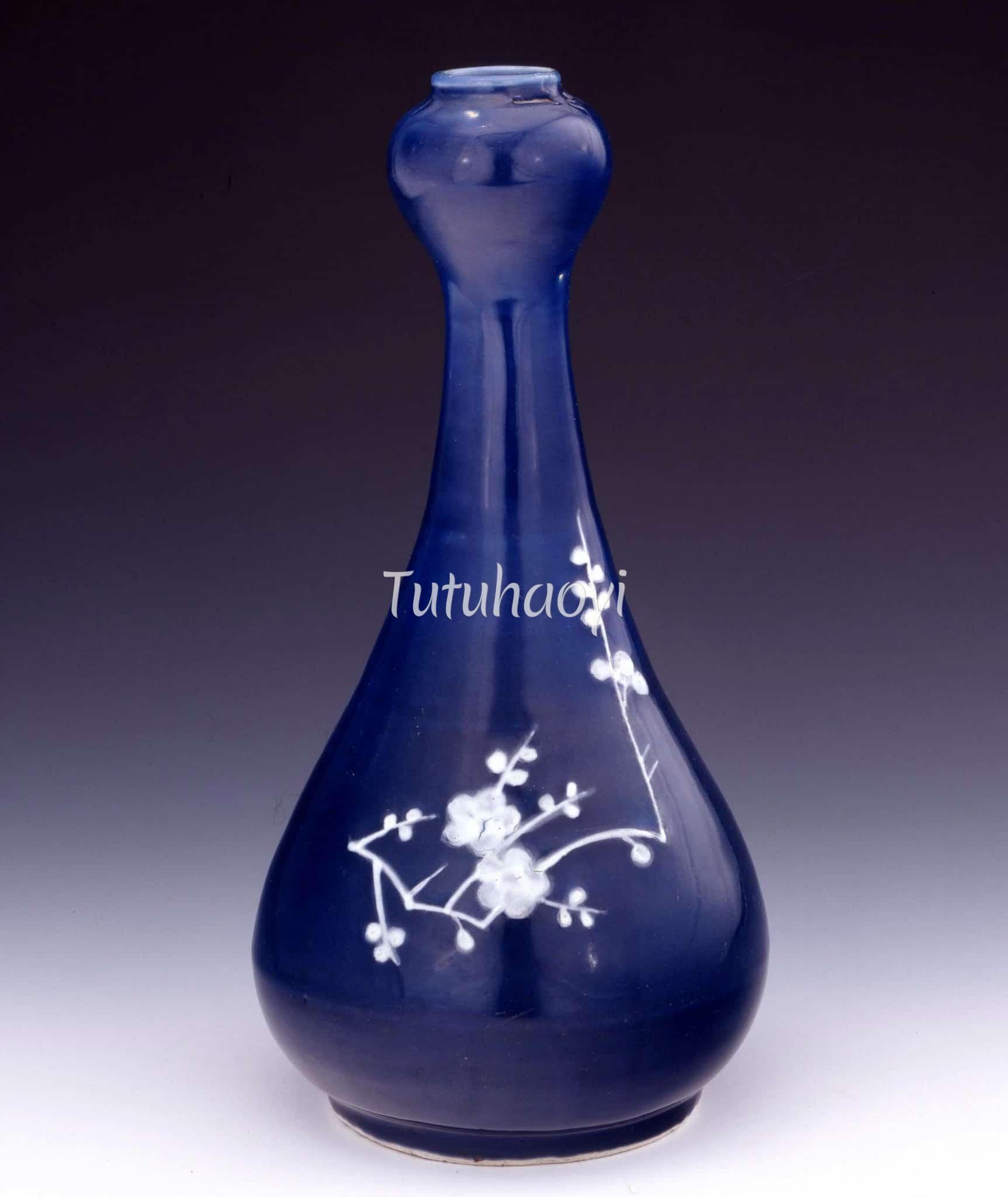

With the pine and bamboo, the plum is one of the Three Friends in Winter 岁寒三友, symbols of strength and endurance. Unlike its fellow plants in this group, the plum is not an evergreen, but it enjoys a special significance as the first tree of the year to blossom, even before the cherry. The briefly-flowering pretty red, white or pink blossoms – which appear before the leaves – signify the imminence of spring, and are emblems of hope, as well as of beauty, virginity and the fleeting nature of existence.

Furthermore, the plum, bamboo, chrysanthemum and orchid constitute what are traditionally known as the Four Gracious (or Gentlemanly) Plants 四君子. The five petals of the plum blossom also symbolise the Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal and water), and the Five Blessings (longevity, wealth, wellbeing and peace, love of virtue, and natural death).

The prunus acquired great popularity as an artistic and poetic motif from the Song dynasty onward, a period when China was threatened and subsequently, under the Yuan (Mongol) dynasty (1279–1368), governed by foreign invaders. For the traditional Chinese scholar-artist, the dilemma of whether to work for the new dynasty and risk being viewed as a traitor, or to withdraw from official life and risk persecution and penury, was a common theme, often necessarily expressed through subtle symbolism. Plum blossom signified courage in adversity – ‘braving the frost’, as the 11th-century poet Wang Anshi 王安石 put it – and, in times such as the Yuan era, the hope of better political times to come.

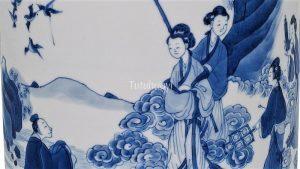

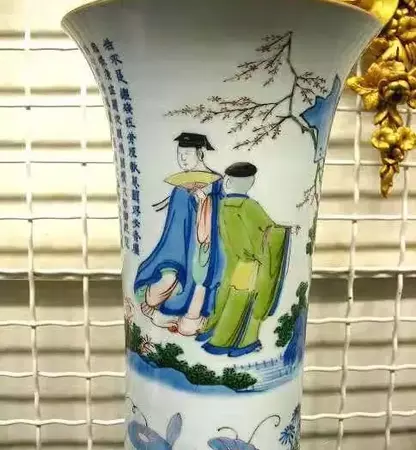

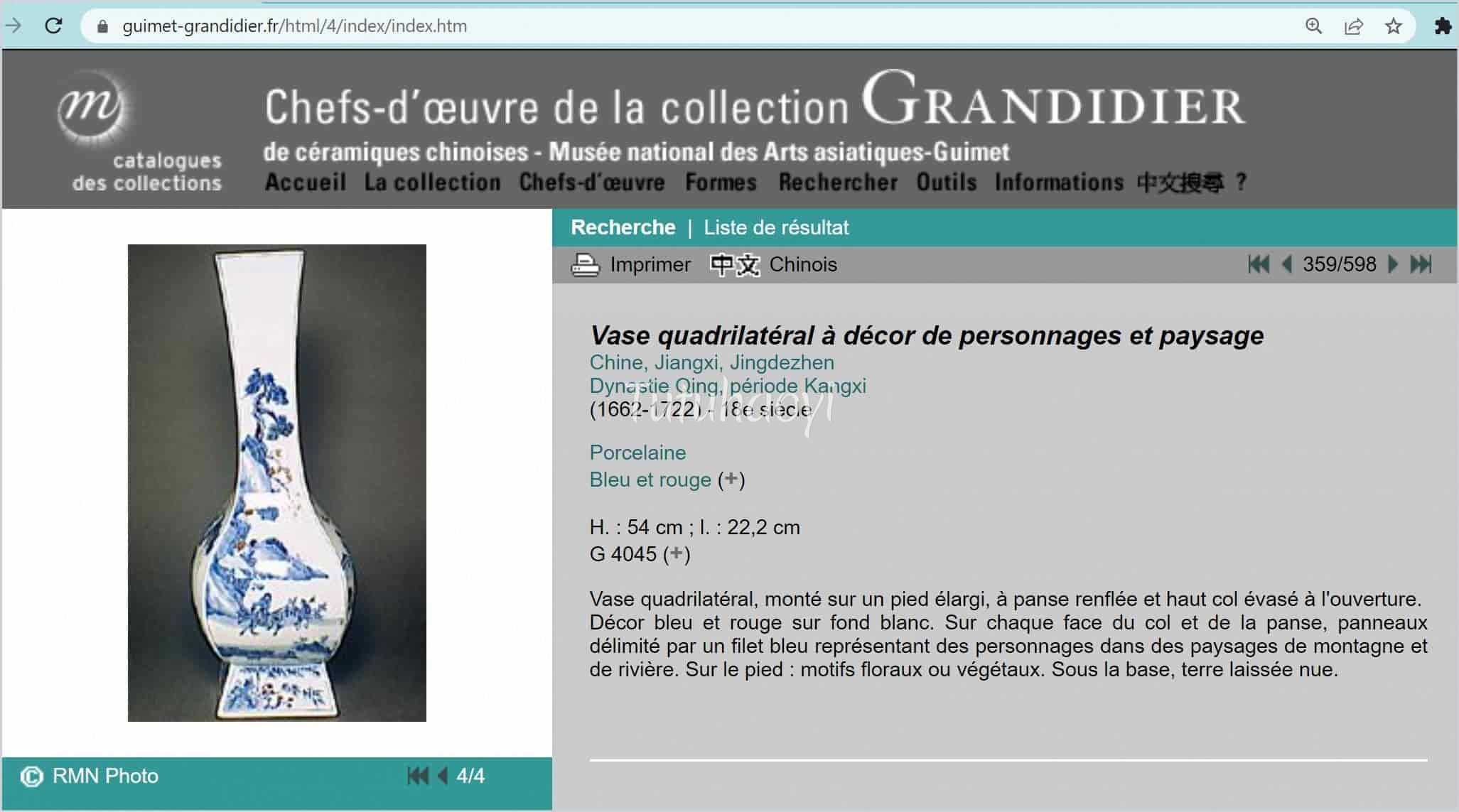

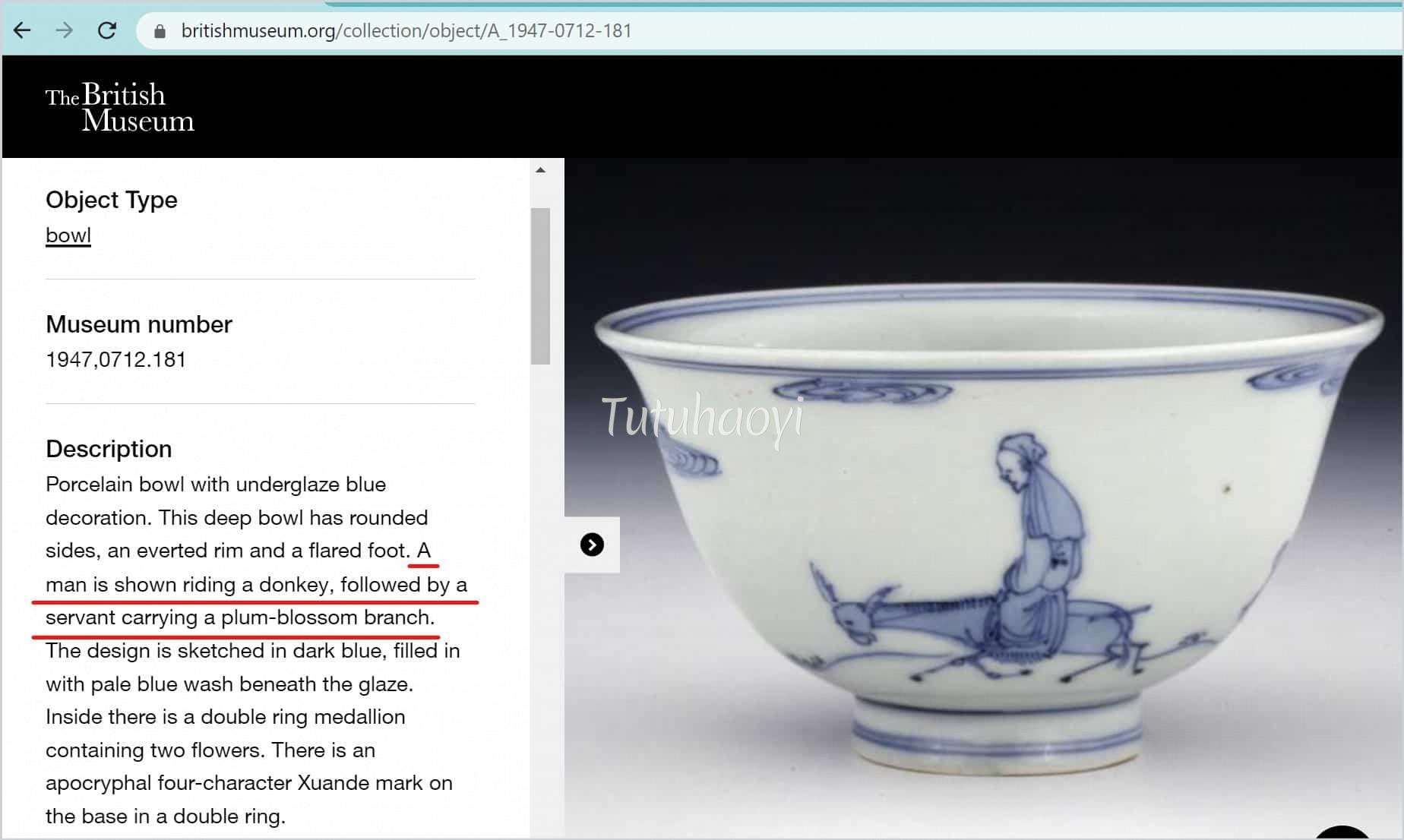

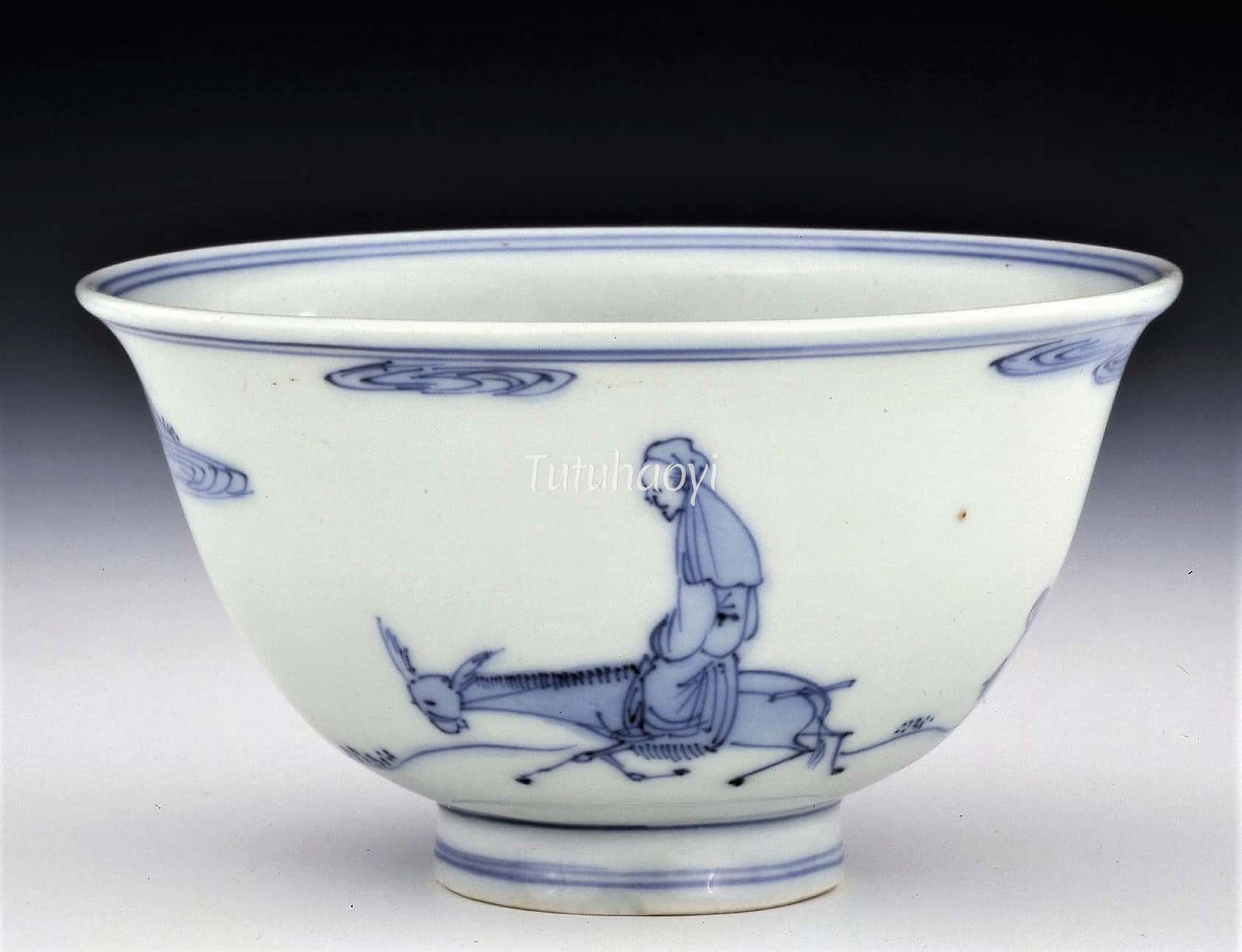

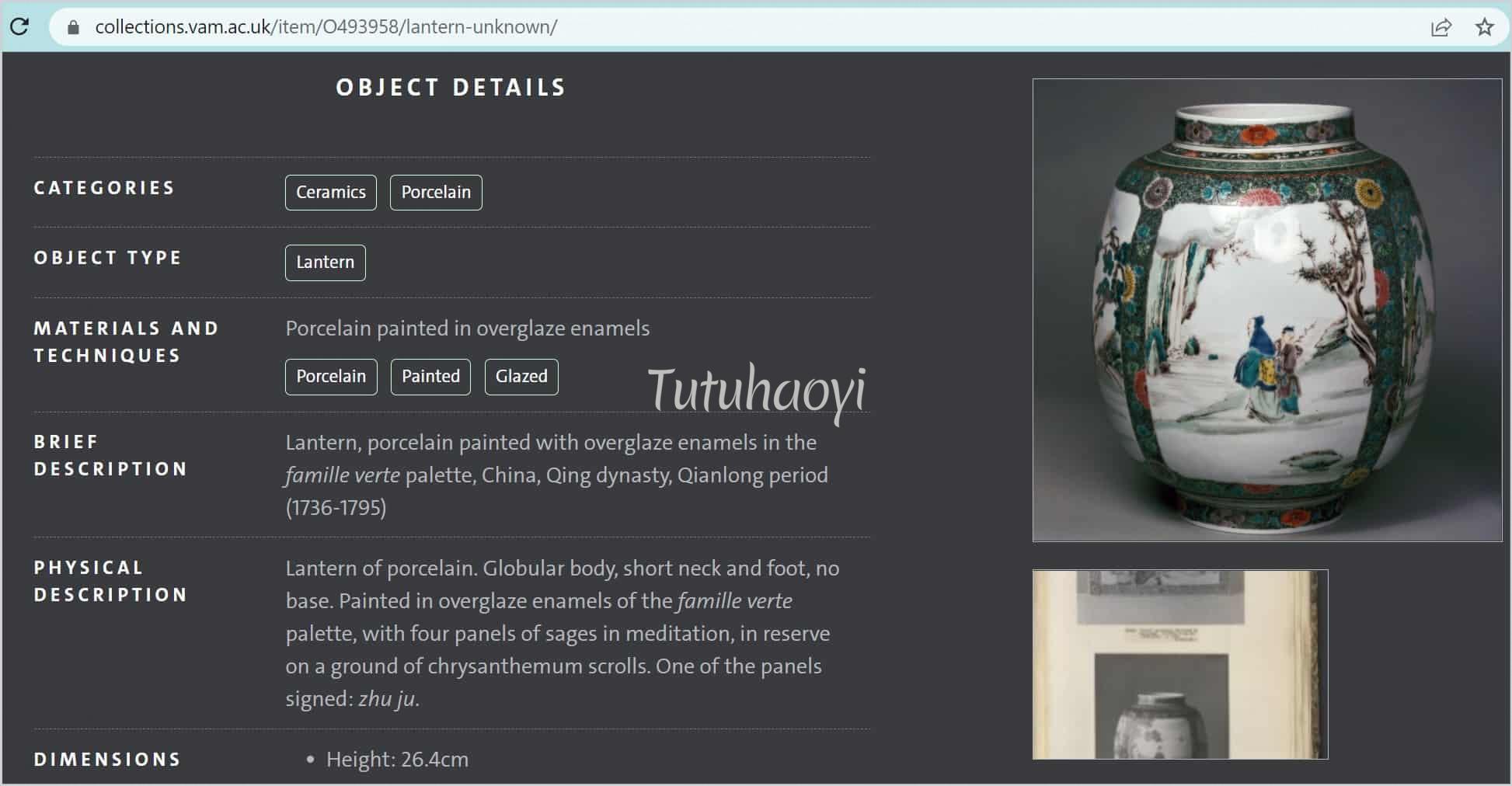

There is a play attributed to the noted Yuan dynasty playwright and poet, Ma Zhiyuan (马致远, c.1250 – c.1324), entitled ‘(Meng Haoran) Looking for Plum Blossom on a Snowy Day’. In the play, Meng Haoran was characterised as a scholar with incredible integrity, symbolised by his love of plum blossom looking its best during the depths of winter. For hundreds of years, Chinese literati have lauded his life-long self-exile from material pursuits in officialdom and held up his deeds as good examples for scholars. Such story scene can be found in the collections of the Guimet Museum, the British Museum, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. However, these renowned museums have not been able to recognise this well-known story scene so far.

Reference:

Jeffrey P. Stamen and Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni (2017), A Culture Revealed: Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection 文采卓然:潔蕊堂藏康熙盛世瓷, Jieruitang Publishing, Bruges, pp. 34–35.