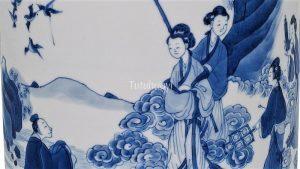

Editor: Correctly identifying figures is crucial to deciphering an obscure story scene. Looking at this featured image, for example, some may think that the two figures in non-specific attires on a dragon and a phoenix are anonymous Daoist immortals. But Dr Yibin Ni would tell you the story otherwise with his analysis of the details of relevant attributes and motifs. The two figures are actually a loving and harmonious couple named Xiao Shi and Nongyu, who are expert in playing wind instruments, a ‘xiao’ flute and a ‘sheng’ mouthorgan. Here are their romantic story and some examples of how some big museums have failed in their attempt to identify the scene.

featured image above: porcelain dish with overglaze enamelled decoration (detail), Kangxi period (1662-1722), courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Duke Mu of the Qin State (秦穆公, died 621 BCE) was one of the so-called Five Hegemons (五霸 wuba) in the Spring and Autumn Period (770 – 476 BCE) (春秋 chunqiu). He had a daughter named ‘Nongyu (弄玉, meaning Playing Jade)’, who was a talented musician excelling at playing the sheng (笙 mouthorgan). Nongyu only wanted to marry her musical match so a recluse genius xiao (箫 flute) player, Xiao Shi (萧史), was discovered and brought to the duke.

The duke was not keen on Xiao Shi at first when he learned that the young man’s musical instrument was different from his daughter’s. However, Nongyu, who was sitting behind the screen listening to the audience, asked Xiao Shi to play a piece on his flute. Xiao did.

As soon as the first piece ended, a gust of fresh air blew in. When the tune resumed, gold-laced rosy clouds gathered from the four directions in the sky. During the third performance, a couple of white cranes danced in front of the duke’s terrace and peacocks flew in! Experiencing the magic spectacle, the duke was pleasantly amazed and his daughter cried with joy, ‘This is my man!’ It happened to be the fifteenth day of the eighth month of the traditional calendar and was supposed to be the lucky day of their marriage. So they had their wedding on that very night.

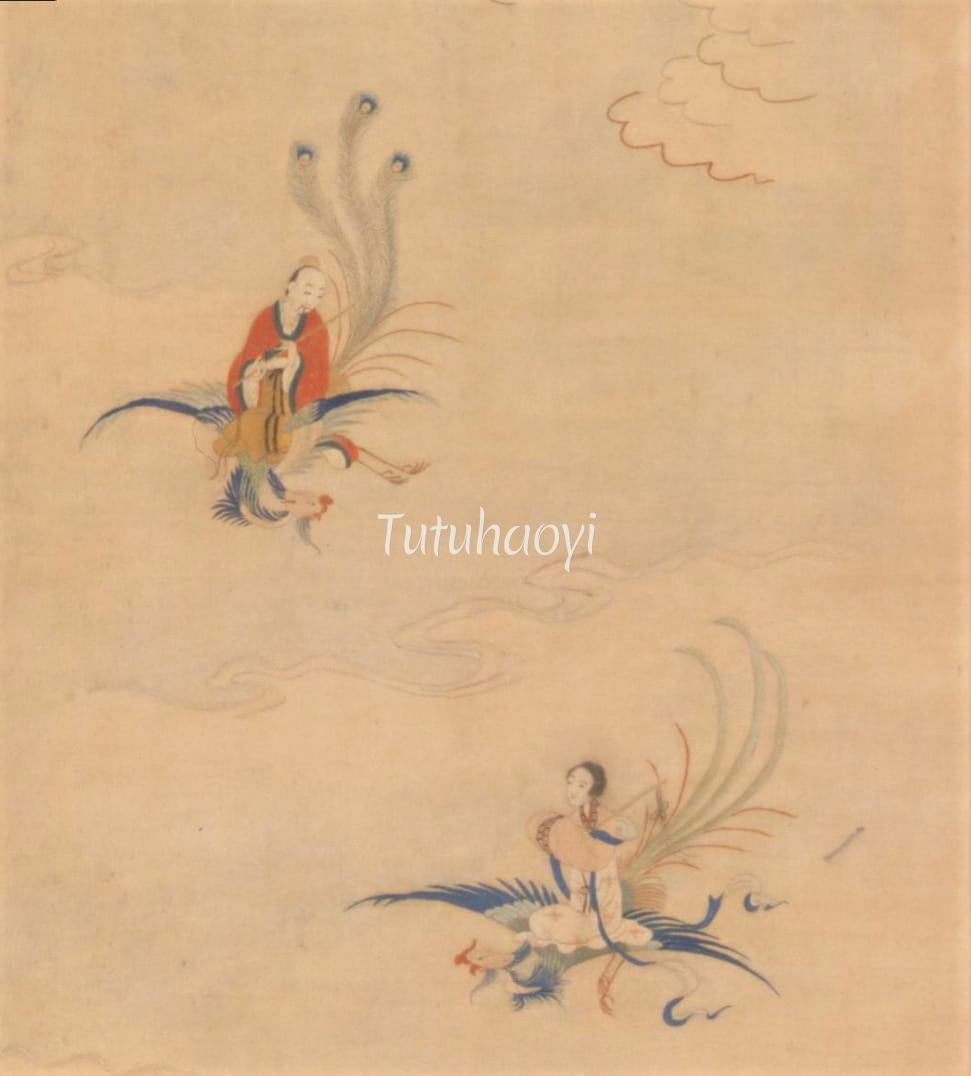

The couple lived happily together for years while Xiao Shi taught his wife to imitate the singing of phoenixes on her musical instrument. Whenever they played together on the high pavilion terrace named ‘Phoenix Terrace’ specially built for them, phoenixes would flock around them. One day, the couple rode on the divine birds ascending to heaven.

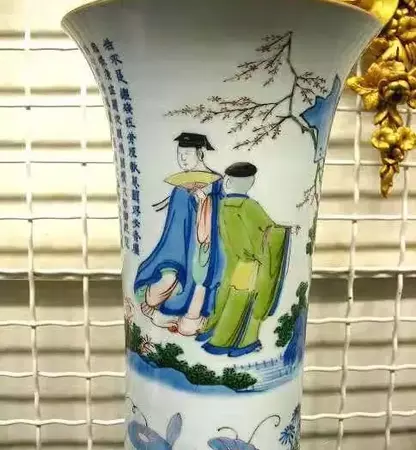

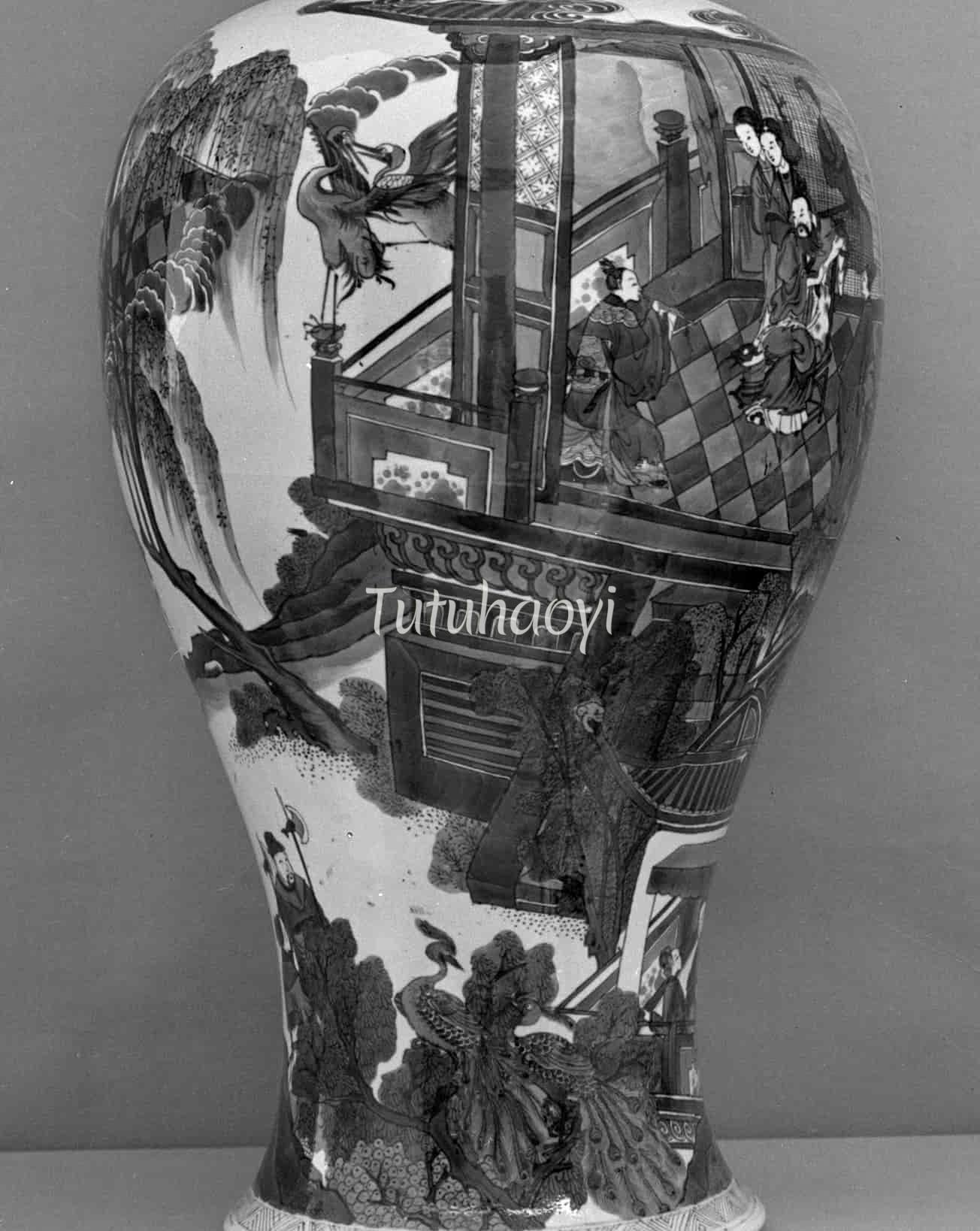

Some of the details from the story have been chosen to adorn a large famille verte yenyen vase in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Disappointingly, on their current online catalogue, the vase is labelled as ‘vase with scenes from Romance of the Three Kingdoms’.

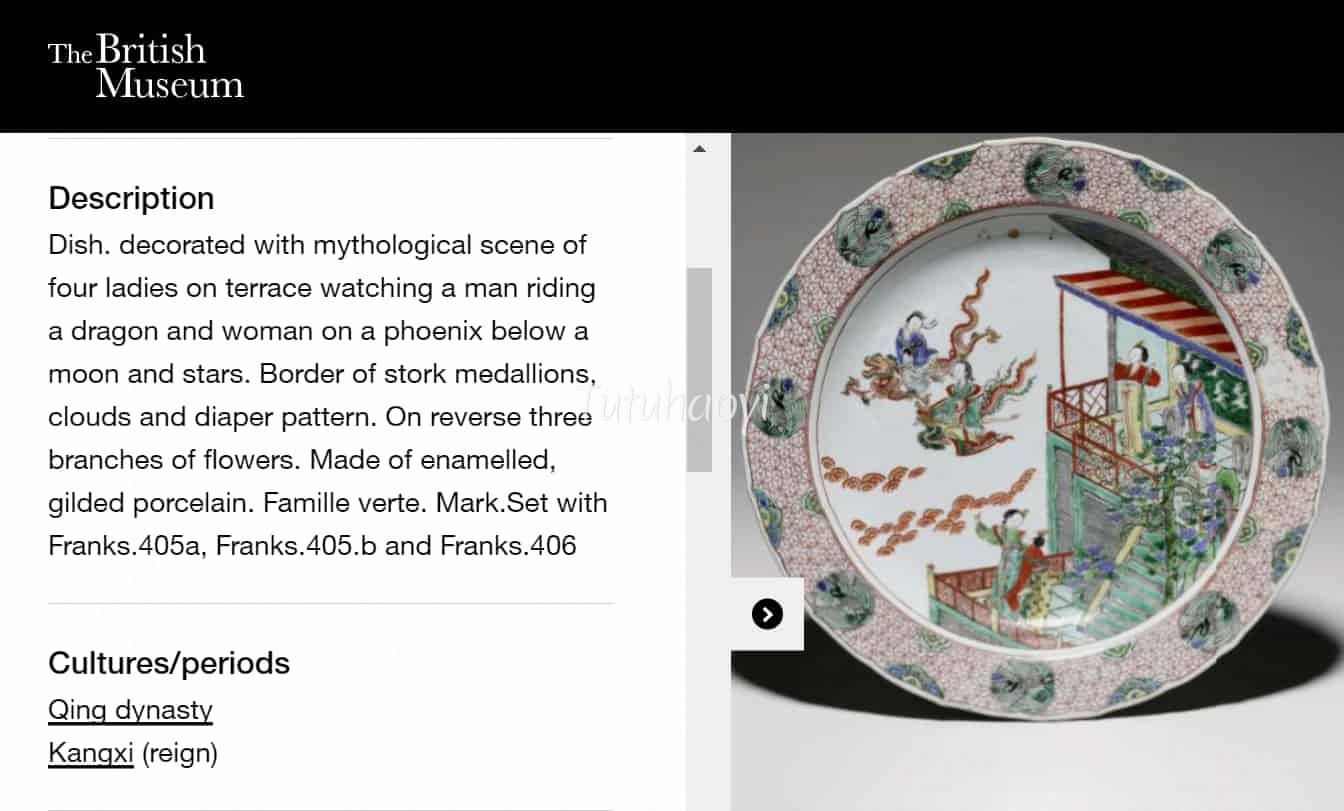

In the collection of the British Museum, there is a large famille verte dish bearing the same story scene in the centre, albeit a slightly different version. This version depicts the moment when the couple ascend to heaven. Xiao Shi is holding a sheng mouthorgan and riding a dragon, which is the ultimate yang male symbol, while Nongyu is carrying a flute and riding a phoenix, which is the ultimate yin female symbol. Their online catalogue describes the decoration as a ‘mythological scene of four ladies on terrace watching a man riding a dragon and woman on a phoenix below a moon and stars’. A romantic story and a harmonious relationship between the couple is thus missed.

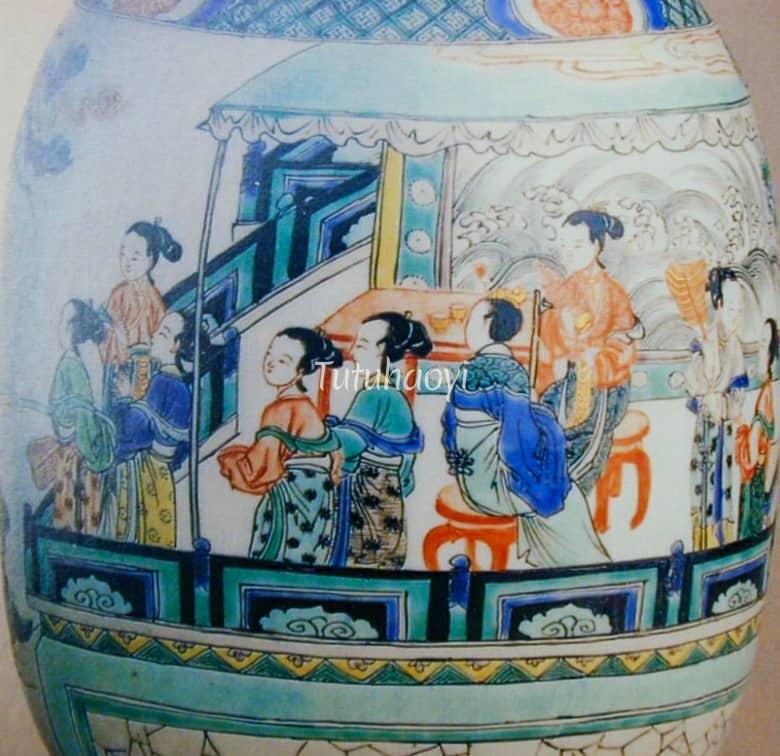

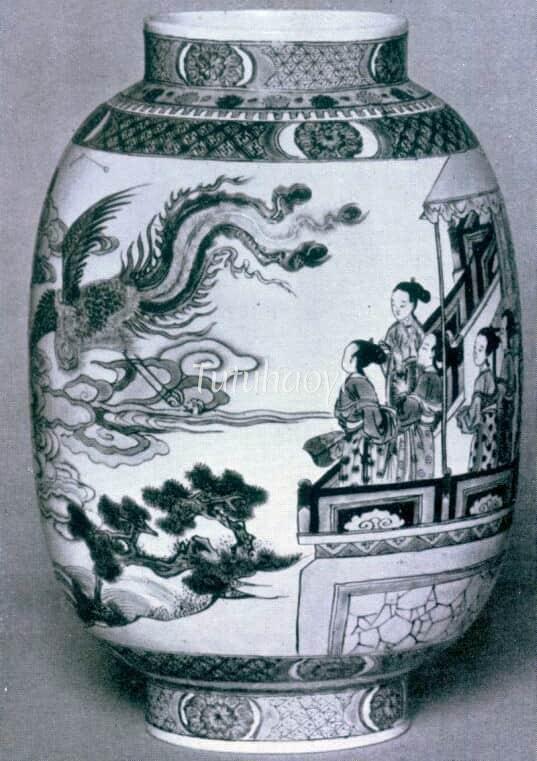

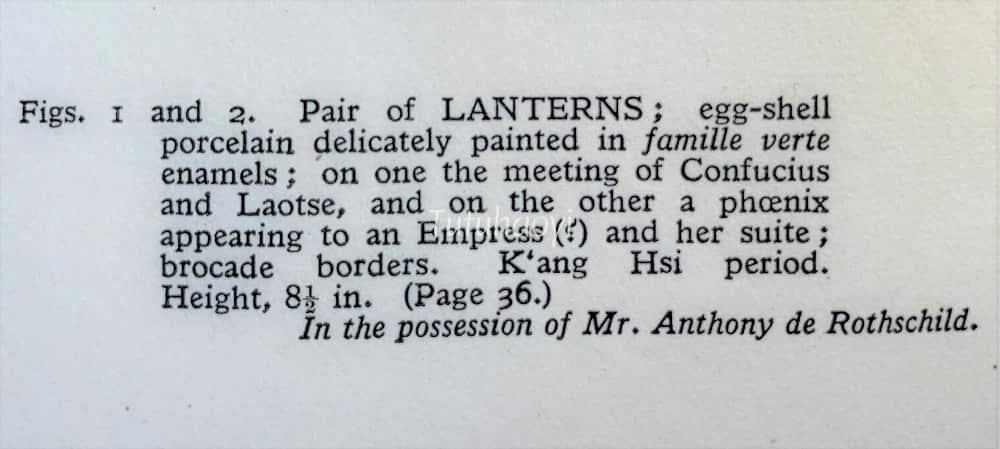

Another authority on Far Eastern ceramics seemed to have missed even the key element in this story scene. Robert L Hobson (1872-1941) was the keeper of the Department of Ceramics and Ethnography at the British Museum. He was praised by the London Times for his cataloguing work in his obituary on 7 June 1941. The influential newspaper described him as establishing firm facts for what had previously been ‘surmise and unproved tradition’. However, Hobson’s verdict on this scene on the Rothschild lantern is ‘a phoenix appearing to an empress (?) and her suite’. The fact that he only acknowledged the existence of the female protagonist as ‘empress’ in the scene shows that he turned a blind eye on the perfectly matching couple in the picture. As a matter of fact, the blissful matrimony is the whole point of this charming tale. The male protagonist Xiao Shi is sitting opposite Nongyu with his back towards the viewer. Xiao Shi is wearing a gold crown and holding his signature flute in his right hand, while Nongyu is wearing a phoenix tiara and cupping a sheng mouthorgan to her bosom.

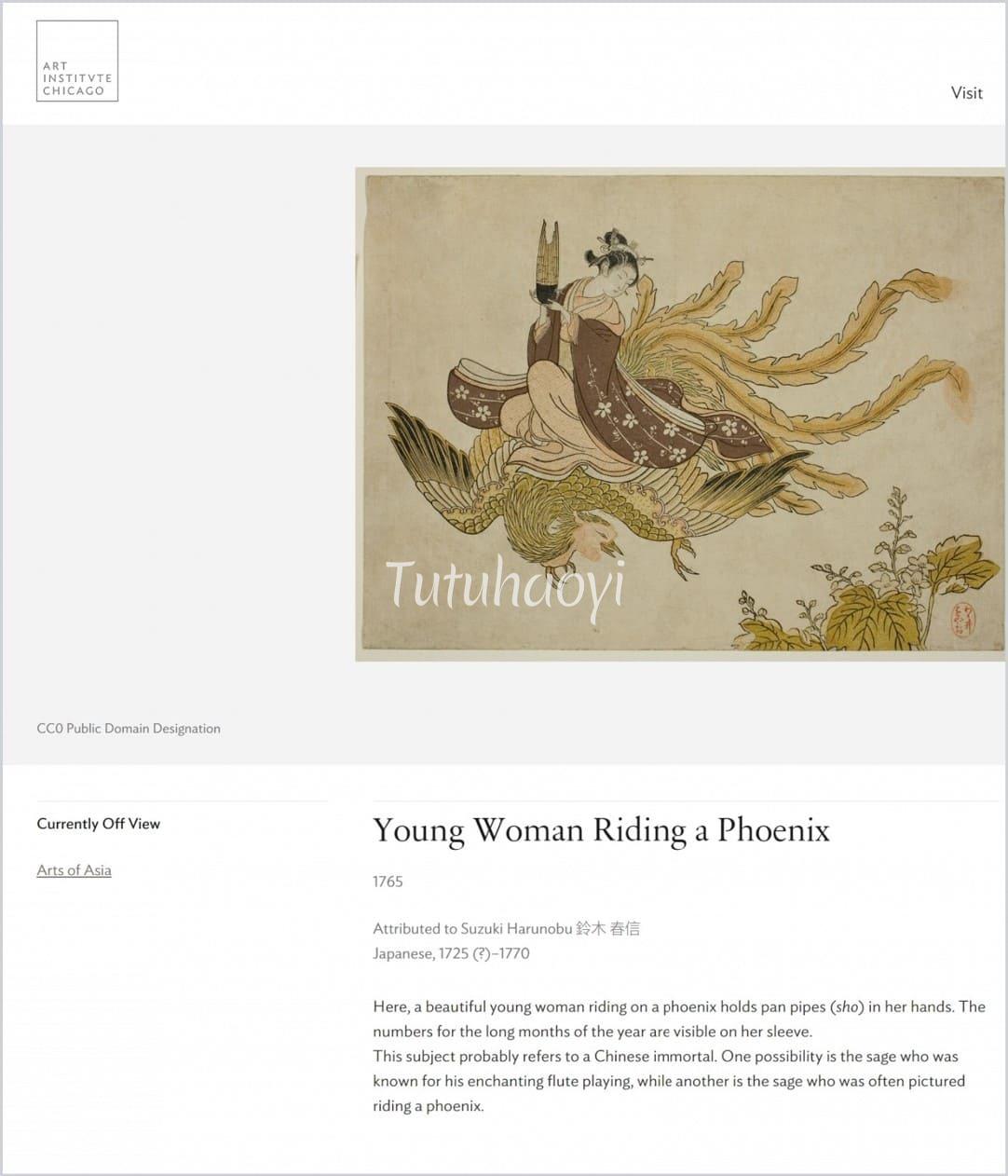

There is a colour print attributed to the 18th-century Japanese print maker Suzuki Harunobu (铃木春信, ca.1725-1770) in the renowned Clarence Buckingham Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago. It was supposed to be a parody of the Nongyu story. In the picture, we can see clearly Nongyu’s attributes the sheng mouthorgan and the phoenix. And also it was a fashion at that time in Japan to design parody scenes of well-known Chinese pictorial literary allusions, such as Laozi and Qin Gao that I have quoted in my previous blog. In all of these parody pictures, the protagonists appear as traditional Japanese geisha women instead of realistic Chinese figures in those traditional story scenes. Not aware of this historic cultural background, the museum has presented the parody of Nongyu’s story by Suzuki Harunobu as ‘Young woman riding a phoenix’, which is only a superficial description, rather than a culturally specific iconographical one.