Editor: ‘Yang Xiang trying to throttle the tiger to rescue her father’ is a well-known story passed down from generation to generation in ancient China. However, Yang Xiang has sometimes been portrayed as a male figure on traditional Chinese artworks. Let’s invite Dr Yibin Ni to explain the reasons behind this puzzling phenomenon.

The ancient story of ‘Yang Xiang trying to throttle the tiger to rescue her father’ is one of the stories in the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (二十四孝 er shi si xiao). The brief story is as follows:

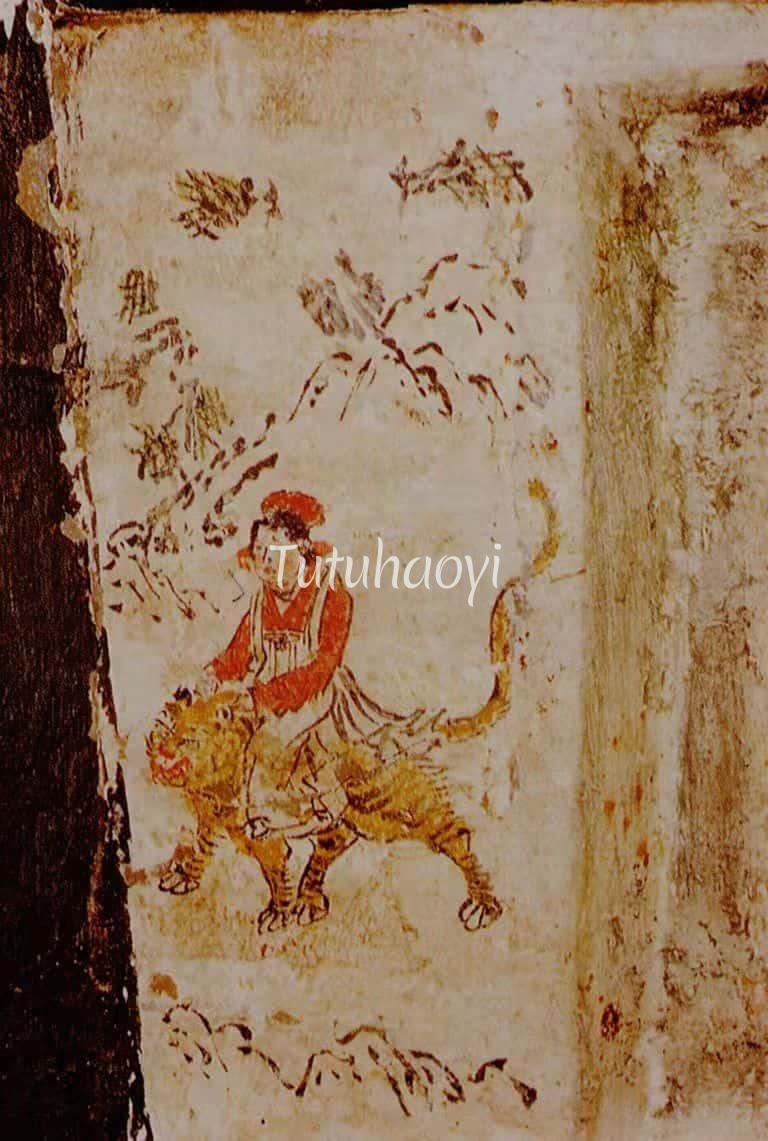

Early in Jin dynasty (晋 265–420), Yang Feng 杨丰 and his teenage daughter, Yang Xiang 杨香, were harvesting the millet crops in the fields when he was attacked by a tiger. Though only fourteen-years-old and without any weapon in her hand, Yang Xiang fearlessly jumped onto the tiger trying to strangle the beast. Her spirit of filial piety was so powerful that even a ferocious wild beast was deterred and ran away. Yang Feng thus survived. The county governor awarded Yang Xiang’s extraordinary good deeds with grains and honouring flags at the gate of their family residence.

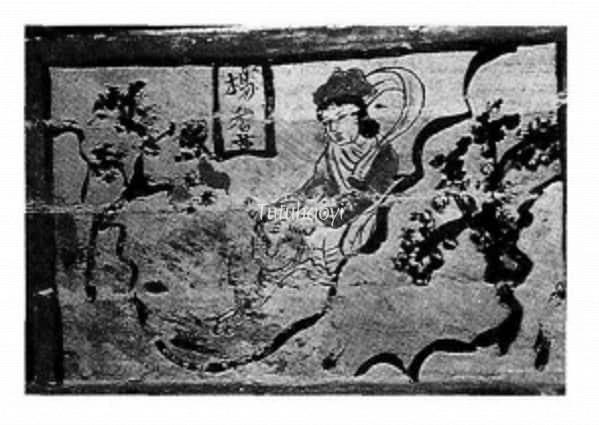

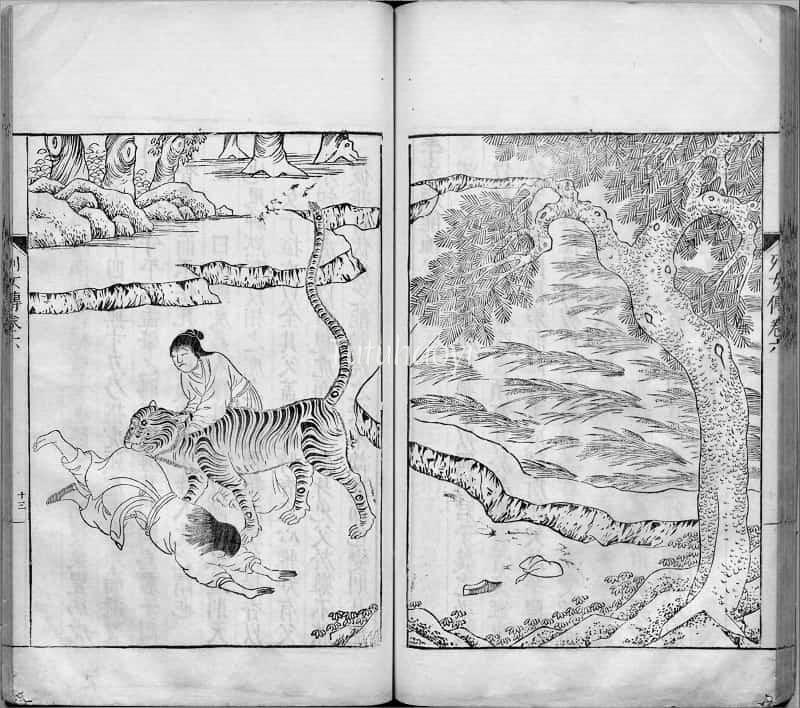

One of the earliest records of this story is found in the Garden of the Extraordinary (异苑 yi yuan), a collection of historical legends compiled by the Liu-Song-period 刘宋 (420–479) scholar Liu Jingshu 刘敬叔 (fl. 417–426). There is a fragment of Yang Xiang’s story survived on the back of Scroll BD14665 in the Dunhuang Manuscripts (敦煌遗书) kept in the National Library of China. The manuscripts were discovered last century in the Mogao Caves (莫高窟 Mogao Ku) of Dunhuang, China. Scholars believe that they date from late 4th to early 11th centuries and thus are relatively reliable textual sources. The fragment specifically says the account is from a version of Biographies of Exemplary Women (列女传 Lienv zhuan). In the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Yang Xiang’s anecdote was canonised in The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, a popular children’s primer attributed to Guo Jujing (郭居敬). The Ming scholar-official Wang Daokun (汪道昆 1525–93) compiled and commissioned the illustrations of the Illustrated Biography of Exemplary Women (绘图列女传 huitu Lienv zhuan) and it contains Yang Xiang’s story. The surviving version of this book is a reprint as part of the series Zhibuzu zhai congshu (知不足斋丛书) organised by Bao Tingbo 鲍廷博 (1728–1814).

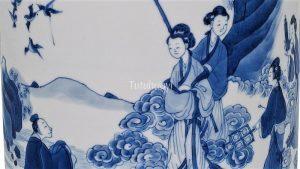

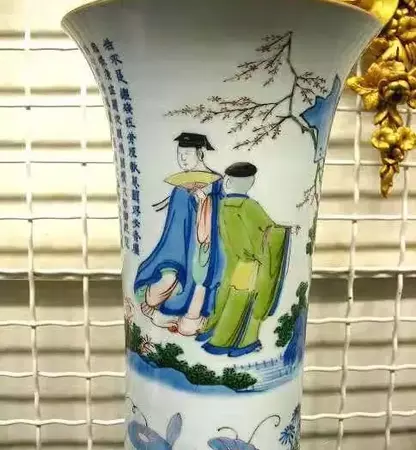

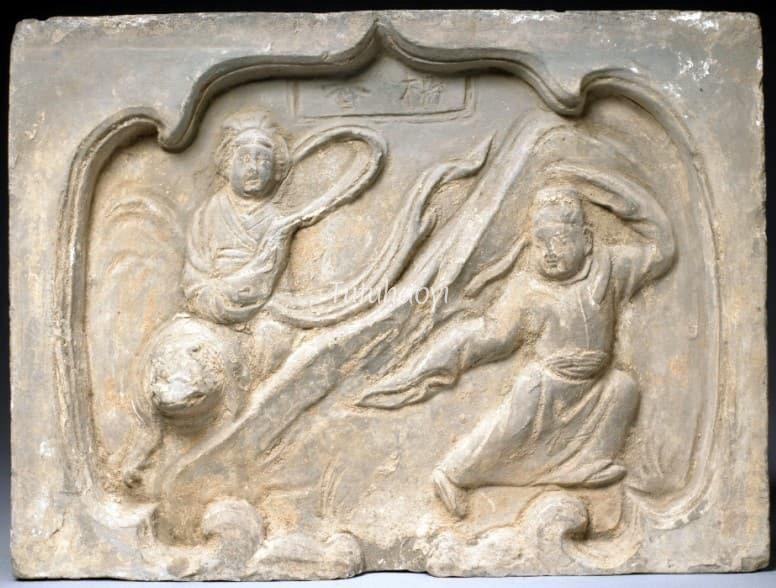

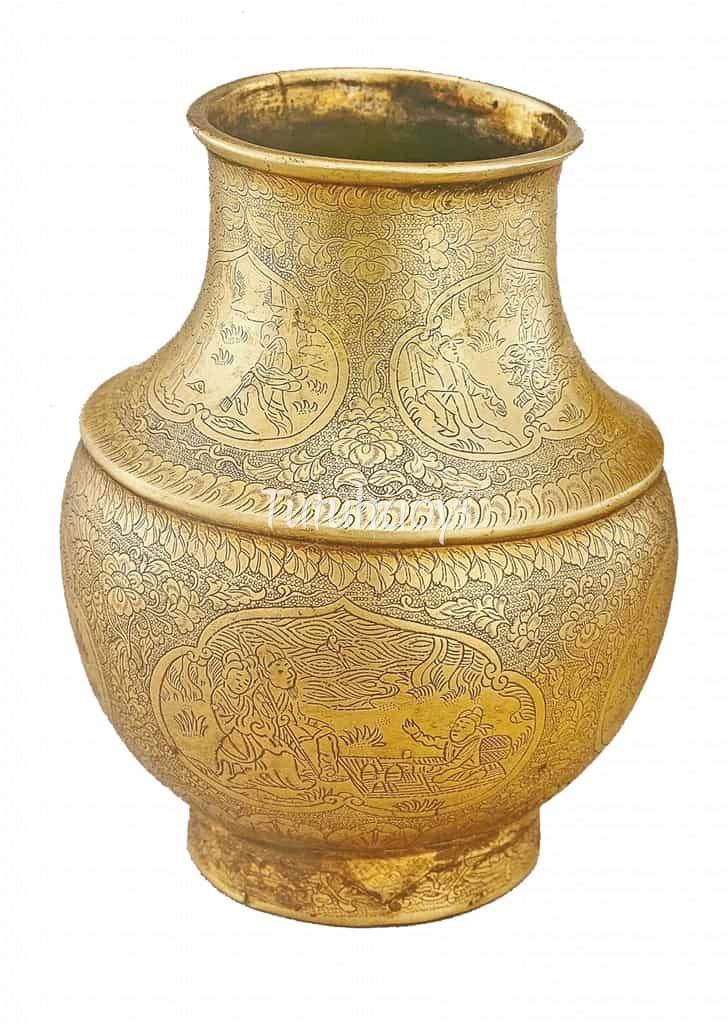

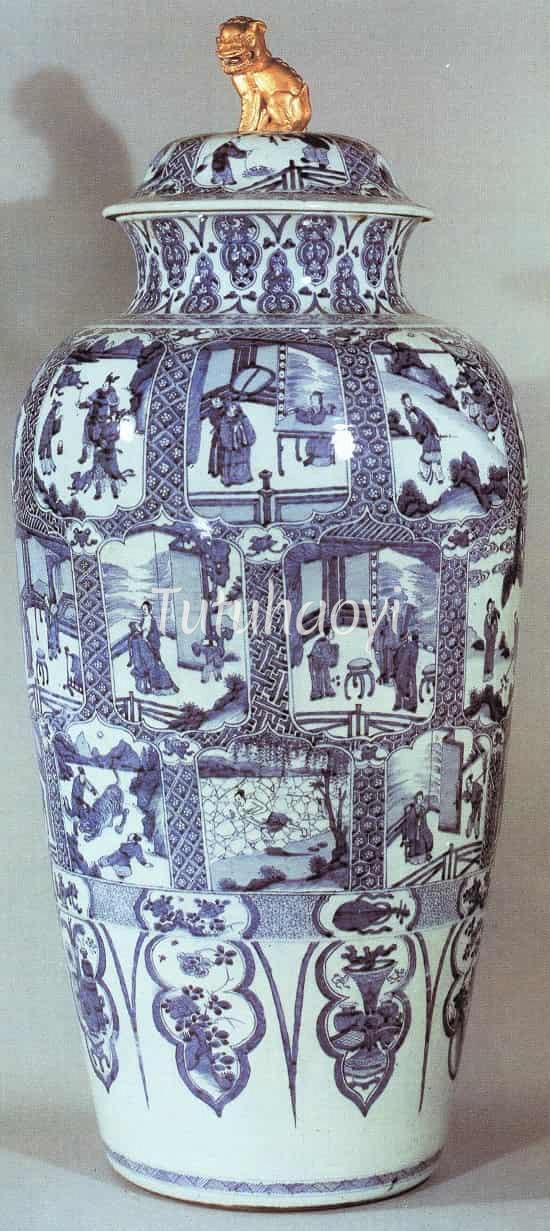

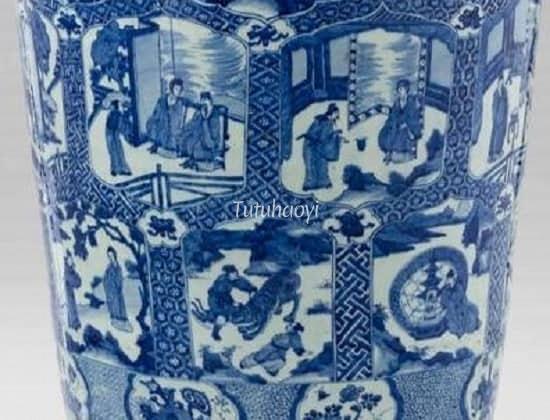

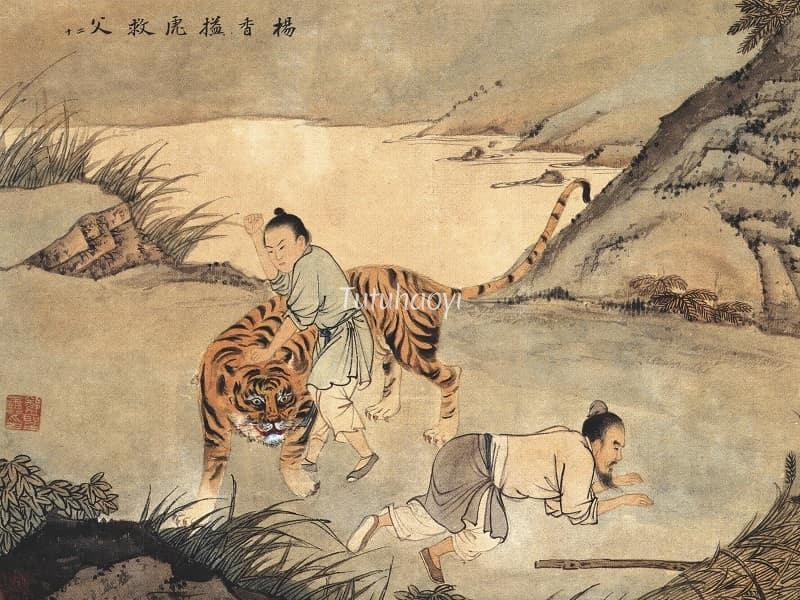

Images depicting Yang Xiang’s heroic deeds excavated from Northern Song (960–1127), Liao (916–1125), Jin (1115–1234) and Yuan (1271–1368) tombs all portray Yang Xiang as female. However, in some illustrations of Yang Xiang’s story created in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the person fighting with the tiger appears to be male, as are seen on Kangxi blue-and-white vases and many of the late Qing illustrations such as the one by Wang Su (王素). The switch could be due to the heavy casualty of the cultural heritage during the Manchu invasion of the Central Plains and the drastic dynasty change from the Han-Chinese Ming (1368–1644) to the Manchu Qing (1644–1911). In a male-dominant ideological environment, once the erroneous ‘man-fighting-tiger’ format was established, it would be difficult to reverse.

The findings and opinions in this research article are written by Dr Yibin Ni.